Scientists and Navy Join Forces

NATO seeks advice to avoid collateral environmental damage

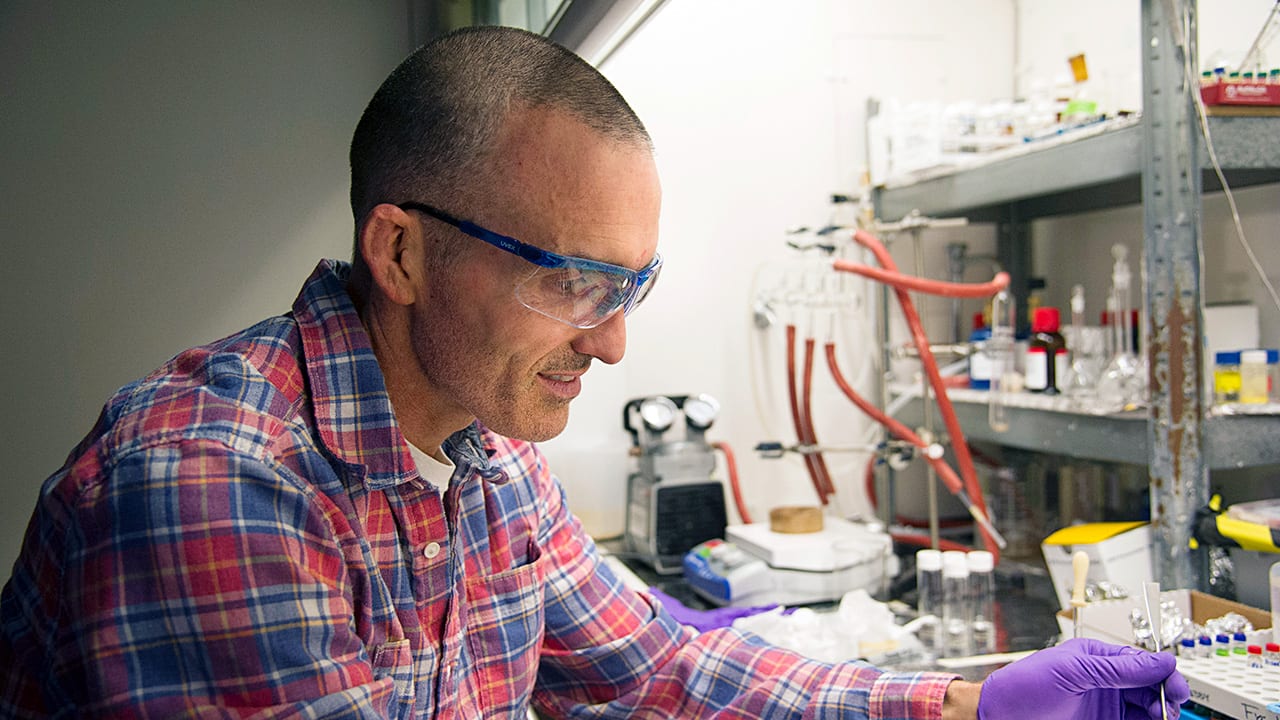

An intriguing email landed in Chris Reddy’s inbox last February. It was the electronic equivalent of a cold call from a Lt. Cmdr. Jason Ziebold of the U.S. Navy, soliciting Reddy’s help.

Reddy, a marine chemist at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, is an expert on oil spills, and Ziebold knew Reddy had played a big role during the Deepwater Horizon disaster in 2010. So when Reddy called Ziebold back, he presumed the Lieutenant Commander might be an environmental health and safety officer.

“He said, ‘Nope, I blow [stuff] up,’ ” Reddy said. “But he had the presence of mind to know that when you do, you can make a big mess. He was asking for expertise on how to avoid a Deepwater Horizon-like oil spill.”

Ziebold was planning for a North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) military exercise, called Cold Response 16, to take place in and off the coast of Norway, that involved about 16,000 troops from 12 NATO and partner countries. In the scenario, an adversary country, Norlandia (northern Norway), invades a NATO ally, Highland (central Norway). NATO forces are charged with repelling the Norlandian invasion.

Among the exercise’s goals was to defeat the enemy while limiting causalities and damage to allies’ critical infrastructure, such as power plants, airports, and hospitals.

But commanders and planners for Cold Response 16 also wanted to limit harm to fisheries and aquaculture from the sinking of ships designed to refuel other ships. Norway has the largest fishing industry in Europe and second by value in the world. Ziebold was charged with researching ways to minimize the significant environmental, economic, political, and publicity impacts of a potential oil spill.

Reddy briefed Cold Response 16 planners on various case studies of previous oil spills, including Deepwater Horizon, and put them in touch with other academic, government, and industry experts. Reddy and the others advised Navy officials on how jet fuel behaves differently than diesel fuel in the environment, and how each affects marine life differently.

They recommended that military planners avoid sinking a ship in shallow waters near land, and that they take advantage of offshore winds and outgoing tides that would move oil away from shore. And they also provided information on environmental impacts in the event of a shallow-water sinking.

Based on their recommendations, NATO forces were able to fictionally “sink” a Norlandia refueling ship during the exercise, choosing a time and area with near-ideal conditions to prevent and mitigate environmental damage.

“We saw this as a successful, mutually beneficially exercise in communication between the military and academic researchers,” Reddy said. “This case exemplifies the value of stakeholders taking the simple but often overlooked step of ‘exchanging business cards’ in the planning stages of events, rather than during active crises. One day, Lt. Cmdr. Zeibold’s email could protect untold lengths of coastline, people’s livelihoods, and the United States’ relationships with allies.”

From the Series

Image

Slideshow

- As Navy officials prepared a NATO military exercise that involved sinking fuel-laden ships, officials solicited help from WHOI marine chemist Chris Reddy, an expert on oil spills in the ocean. He provided scientific advice on how to plan to mitigate collateral environmental damage. (Tom Kleindinst, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

Related Articles

- The ocean currents behind Brazil’s pollution problem

- Sunlight and the fate of oil at sea

- A toxic double whammy for sea anemones

- WHOI scientists discuss the chemistry behind Sri Lanka’s flaming plastic spill

- Oil spill response beneath the ice

- WHOI scientist shares her perspective on ‘imminent’ oil spill in the Red Sea

- Rapid Response at Sea

- The Sun’s Overlooked Impact on Oil Spills

- Investigating Oil from the USS Arizona