Oil spill response beneath the ice

Test deployment of WHOI vehicle expands Coast Guard capabilities

Estimated reading time: 5 minutes

The ability to rapidly respond to an oil spill in the Arctic just got even faster, following the successful test deployment of a long-endurance robot between the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution and the U.S. Coast Guard (USCG).

On April 15, at a baseball field in Woods Hole, Massachusetts, a Jayhawk helicopter levitated within throwing distance of an ogling crowd of locals and their children. The package it came to pick up was a yellow and orange autonomous underwater vehicle (AUV) capable of long-duration missions underneath a mosaic of Arctic sea ice. For Coast Guard officials, it promises to be the first rapid-response tool capable of identifying and tracking oil under ice in the event of an environmental disaster. That's an increasingly possible problem as Canada's Northwest Passage becomes a more attractive crossing for ships and industries looking to tap the region for oil and natural gas.

"Everyone asks, 'If we had an oil spill in the Arctic tomorrow would you be ready?' and the answer is yes," says WHOI lead engineer Amy Kukulya with confidence.

The robot, known as Polaris, or the Long-Range Autonomous Underwater Vehicle (LRAUV), is a slender, 9-foot submersible, with a customizable payload of sensors capable of sniffing out the slightest whiff of oil and diesel fuel. At just 250 lbs, it is one of the most portable AUVs that could be deployed in the Arctic, something Kukulya and her team at WHOI's Scibotics Lab say is a game-changer for ease of use in an emergency.

"At the end of the day, you have to be able to get the vehicles in and out of the water, and that's usually the bottleneck," says Kukulya. "We've launched [Polaris] from kayaks, stand-up paddleboards, skiffs, and a fishing pier."

During the field test in Woods Hole, Kukulya and Coast Guard avionics specialist Fernando del Cid were able to dolly Polaris over to the helicopter. Then, Coast Guard aviation personnel attached it to a line and releasable swivel hook system, affectionately called "Brutus." Within just 10 minutes, Polaris was airborne-soon, a giant, pill-shaped dot in the distance.

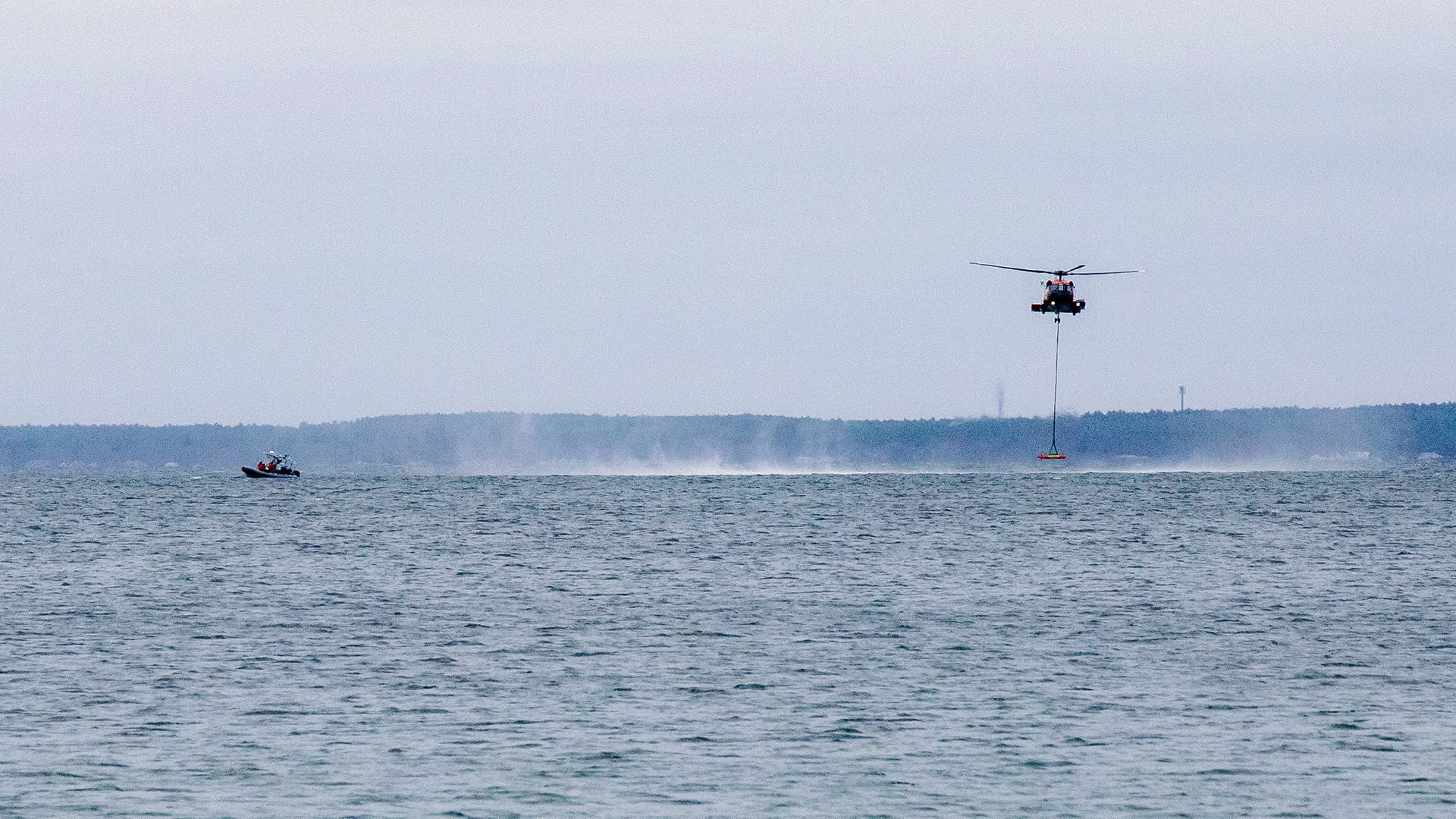

From there, the dangling vehicle was flown at different speeds to test its stability, until eventually being released into Buzzards Bay, where a Zodiac driven by Kukuyla's colleagues waited to assess its performance in the water.

A USCG Jayhawk helicopter releases LRAUV near the Scibotics Team aboard a Zodiac in Buzzards Bay, where the team can inspect the vehicle's systems underwater. (Jayne Doucette, © Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

Once underwater, Polaris can switch from an active, propeller-driven system to a passive, drift mode in order to conserve energy. That hybrid design can extend its mission time up to 15 days under the Arctic ice, at depths of up to 1,000 feet, and allow it to cover more than 1,000 miles of distance. That's enough time for operators to safely retrieve it in between periods of turbulent Arctic weather.

"This [capability] will give us a new operational way to deploy," remarks Captain Kirsten Trego, LRAUV's Coast Guard Headquarters project champion. The Arctic region is more open to human use today than in the past she adds. "Therefore, there's an increased risk of accidents."

While there hasn't yet been an oil spill within the boundaries of the Arctic Circle, previous disasters have come close. M/V Selendang Ayu, a Panamax cargo ship, cracked in half after running aground along Alaska's Aleutian Island chain in 2004, spilling more than 350,000 gallons of oil and diesel fuel along the coast.

Malaysian Panamax cargo ship, M/V Selendang Ayu, is seen split in two after running aground outside of the Aleutian Islands, Alaska in 2004 (Image Courtesy of the U.S. Coast Guard)

Traditionally, easy-to-reach spills can be tracked using a fleet of spotter planes, patrolling vessels, and deep-sea robots that can detect the oil's dissolving hydrocarbon signature. Selendang was far enough south where that could be possible. At higher latitudes, this sort of rapid response becomes harder to execute.

With Polaris, Kukulya and her team hope to provide X-ray-like vision below the ice sheet. There, chemical readouts sent from the vehicle to nearby acoustic buoys can determine how much oil there is, where it's spreading based on the currents, and the best locations to mitigate the damage.

"It makes perfect sense to work with the Coast Guard…they're stewards of our waterways," adds Kukulya. "To be able to make our equipment as simple as possible, so they can come and use their ships and their aircraft to operate it, really completes a powerful collaboration that will take our research and capabilities to the next level."

LRAUV's base design was initially developed a decade ago by a team at MBARI led by now-WHOI Director of the Consortium for Marine Robotics, Jim Bellingham. Today it joins 11 active projects within the Arctic Domain Awareness Center (ADAC), another consortium that operates under the auspices of the Department of Homeland Security to meet the evolving needs of the U.S. Coast Guard. Officials say Polaris is on track to meet those needs after its deployment.

"The trial we did with WHOI was more importantly about recognizing that we can deploy this vehicle anywhere we want, [even in] remote sites," says del Cid.

The ADAC program currently supporting the LRAUV's R&D is set to conclude in June, 2022. By then, Kukulya and her team hope to have upgraded Polaris's status to a Congressionally-funded project, or "Center for Expertise." To achieve that, the Scibotics Lab has already begun to expand the vehicle's other capabilities, from high-resolution mapping to a dynamic docking system that could keep the vehicle in the water indefinitely.

"We're far from having a tool that's one-stop shopping," says Kukulya. "But I think today was a bigger success than I could have imagined."

Noa Yoder (left) and Ryan Govostes (right) of the Scibotics Lab return on a Zodiac with Polaris to debrief with Amy, after retrieving it from Buzzards Bay. (Photo by Daniel Hentz, © Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)