WHOI scientist shares her perspective on ‘imminent’ oil spill in the Red Sea

As a major oil spill looms in the Red Sea, a WHOI physical oceanographer shares her insights on where the oil might go.

Estimated reading time: 4 minutes

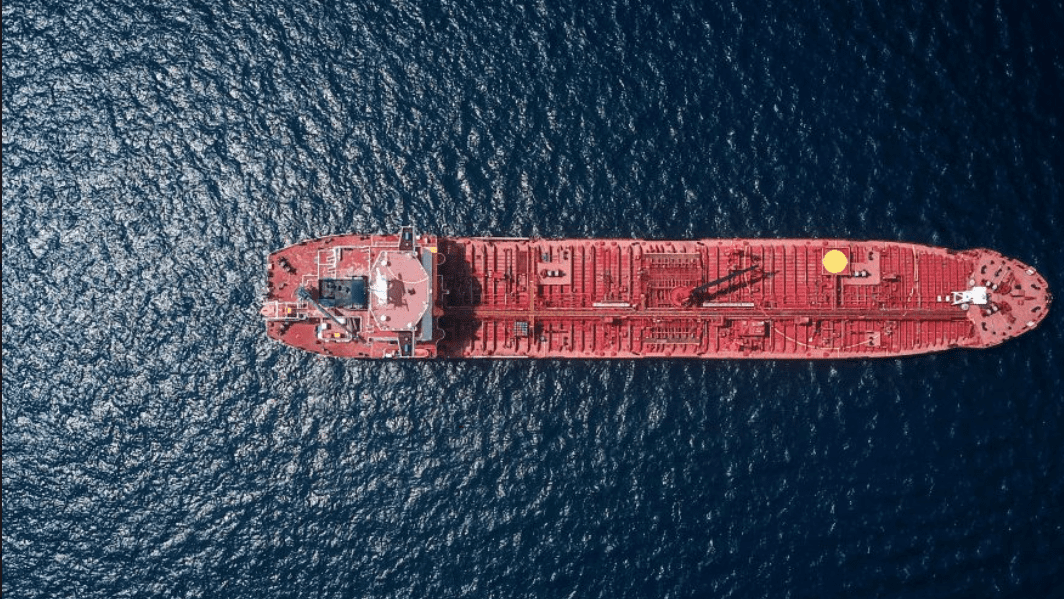

A pool of black oil shimmers on the tanker’s rusty red deck. It’s not fresh oil, but rather, a sheet of fossilized sludge that hints at the vessel's deteriorating condition and dire need of maintenance.

The FSO Safer is a 1,200-foot-long oil carrier moored in the Red Sea that holds an estimated 1.1 million barrels of crude oil. It has been acting as a floating storage unit off the Yemen coast since Ronald Reagan was in office. Owned by Yemen's national oil company, the Safer Exploration & Production Operation Company (SEPOC), the vessel is a “floating bomb” according to experts who have been monitoring it. They say the ship’s rusty hull and corroded pipes put it at risk of injecting more than four times the amount of oil into the ocean than 1989’s infamous Exxon Valdez oil spill.

“It’s not a question of will it spill oil, but when,” says Dr. David Soud, head of research and analysis for international consulting firm I.R. Consillium. He spoke at a recent webinar about the pending crisis.

Viviane Menezes, an assistant scientist in WHOI’s physical oceanography department, says the geography of the Red Sea could exacerbate the effects of an oil spill, an incident that researchers called 'imminent' in a recent report in Frontiers in Marine Science. The inlet is relatively narrow and closed-off, and currents could spread oil across the entire region, depending on the time of year the spill occurred. “It’s like a lagoon—everything is connected,” she says.

Menezes hasn’t been called to analyze this situation, but her decade spent working in the offshore oil and gas industry before becoming a scientist offers field perspective. Since 2015, she’s been studying currents and weather patterns in the Red Sea. She uses instruments deployed by WHOI scientists Amy Bower and Tom Farrar, along with colleagues from King Abdullah University of Science and Technology.

Menezes says that understanding how a spill could play out from an ocean physics standpoint is the first step in preparing for it. “You can look at different scenarios and from that, determine the probability of what may happen here or there, and have a better idea of where to go to contain the oil,” she says.

For instance, Menezes says that oil would spread differently depending on the season. During the winter, currents would bring oil from the southern part of the Red Sea to the northern part. During the summer, however, eddies—swirling currents of water that can be as wide as the Red Sea itself—could spread oil towards the African coast and possibly into the Gulf of Aden and Arabian Sea. “This means you’d have a big disaster hitting coastal regions of different countries,” she says, “many in the list of the world's poorest economies.”

Menezes describes these as “typical scenarios,” but the range of possibilities is more nuanced, making it hard to forecast the consequences of an oil spill on the marine environment. She explains that air-sea interactions in the Red Sea may affect the currents. During the winter, for example, wind jets scream through desert mountain gaps and blow straight out over the water. This leads to “dry-air outbreaks” that cause seawater to evaporate at high rates. This, in turn, causes the Red Sea’s circulation to overturn like a conveyor belt and propels surface currents northward.

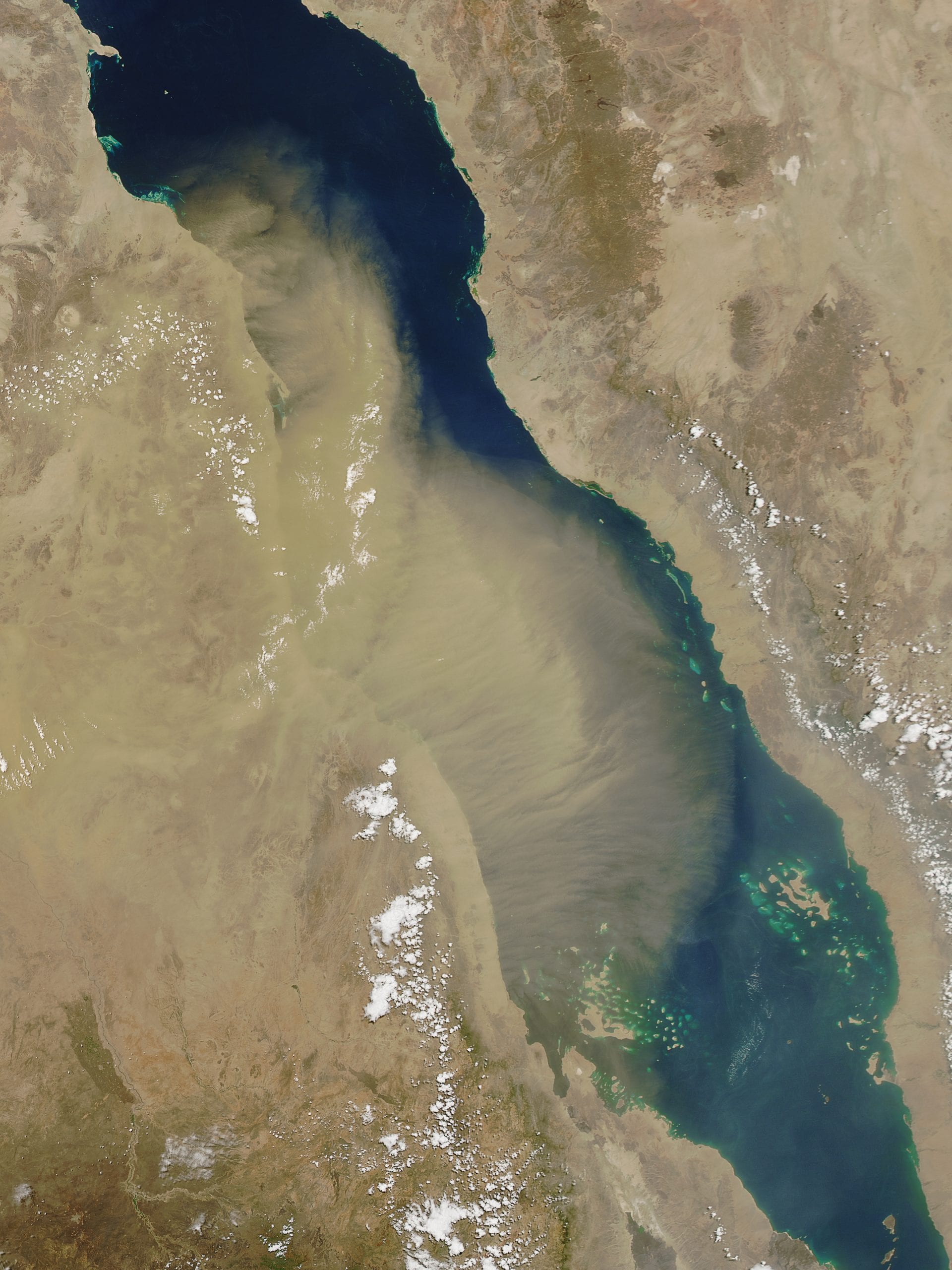

Mountain-gap winds blow dust into the Red Sea. (Photo by Jeff Schmaltz, LANCE/EOSDIS Rapid Response)

By contrast, in the summer months, shifting monsoon winds blow north to south most of the time. Bursts of zonal winds through the Tokar Gap on the Sudanese coast are also common. These strong, summertime wind events, which often create striking dust storms, and generate eddies that can reach Saudi Arabia on the other side of the Red Sea. Because these wind events affect the vertical structure of the ocean, Menezes says they could contribute to oil sinking and upwelling along the oil spill pathway should a spill occur.

Whatever the season, the impacts of a rupture, or even an explosion, of the FSO Safer would likely be substantial. It could devastate the Red Sea's unique coral reefs, which have adapted to living in some of the world’s hottest and saltiest seawater. Desalination plants throughout the region could become contaminated, choking off access to clean drinking water for millions. And a spill could cripple the global economy by forcing temporary closures of Red Sea shipping lanes, which are among the world’s busiest.

But despite the deteriorating condition of the Safer and the growing risk of a major spill, there’s no clear solution on the horizon. The tanker sits in a conflict zone, and unrest in the region, underscored by Yemen’s ongoing civil war, has prevented what Menezes feels is the ideal solution: safely removing the oil from the tanker. The United Nations has made plans on several occasions to inspect the vessel and initiate salvage operations, but has yet to do so. It delayed a mission earlier this month because the organization failed to receive a written security guarantee from Houthi insurgents who control Yemen’s northwest coastline.

Given what we know about the state of the tanker and the likely impacts of an oil spill, doing nothing right now, is, according to Menezes, “insane.”

“It’s very strange because you know it will happen and it will be complicated to clean up,” she says.