Red TideGone for Now, But Back Next Year?

WHOI researchers extend investigations of the Alexandrium bloom of 2005 and look for signs of future trouble

The historic bloom of toxic algae that blanketed New England waters and halted shellfishing from Maine to Martha’s Vineyard is over. But scientists are now wondering if there will be an encore.

Researchers from Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution and from federal and state agencies has found that the massive “red tide,” as it is popularly known, has dissipated in most of southern New England (though the bloom season is just beginning in northeastern Maine and the Bay of Fundy). Alexandrium fundyense, the microscopic marine plant that caused so much trouble, has either run out of food, washed out to sea, or it has been eaten or outcompeted by other microscopic plants and animals.

Before departing, however, the algae likely left behind a colonizing population that could bloom in southern New England for at least the next few years. WHOI Senior Scientist Don Anderson and a team of algae specialists have found evidence that the Alexandrium cells produced cysts—a hardy, seed-like form of the plant that can lie dormant in seafloor sediments until growing conditions are favorable again.

Vice Adm. Conrad Lautenbacher, administrator of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, announced on July 14 in Woods Hole that the agency has awarded $540,000 to WHOI to continue studies of the 2005 bloom and to work toward predicting if and when the algae might resurface in the waters of southern New England. “This work comes at a critical time,” said Lautenbacher, “because we would like to be able to forecast future blooms so that coastal managers can mitigate the impacts on the public and the economy.”

The WHOI team will return to sea in September and October to survey the cyst population in the sediments; they also will continue their lab-based computer modeling of how Alexandrium cells develop and spread in coastal waters around the Gulf of Maine. In spring 2006, researchers will assess ocean conditions and, in particular, the extent to which the newly deposited cysts might be initiating blooms farther south (such as in Massachusetts Bay and Cape Cod Bay). Their models should allow them to forecast locations where blooms are likely.

“We have to determine if Alexandrium has taken another giant step down the East Coast,” said Anderson. “Will Alexandrium flourish off Massachusetts? I have good reason to believe it will.”

April showers and May blooms

The 2005 bloom of Alexandrium fundyense was the most widespread and intense since a hurricane in 1972 spread the toxic algae throughout southern New England waters. Unusual northeasterly wind patterns, prodigious winter snowmelt and spring rains, and remnants of a late-season 2004 bloom in western Maine made conditions ripe for the massive outbreak of 2005. (Read more in “Seeing Red in New England Waters.”)

In most years, Alexandrium grows to toxic levels in Penobscot Bay and Casco Bay in Maine and in Canada’s Bay of Fundy. The more intense blooms can lead shellfish wardens and coastal managers to shut down clam, oyster, and mussel beds for fear of paralytic shellfish poisoning. The potent neurotoxin from Alexandrium accumulates in the meat of filter-feeding bivalves, and while it does not harm them, it can cause paralysis and respiratory problems in humans and other animals that eat the shellfish.

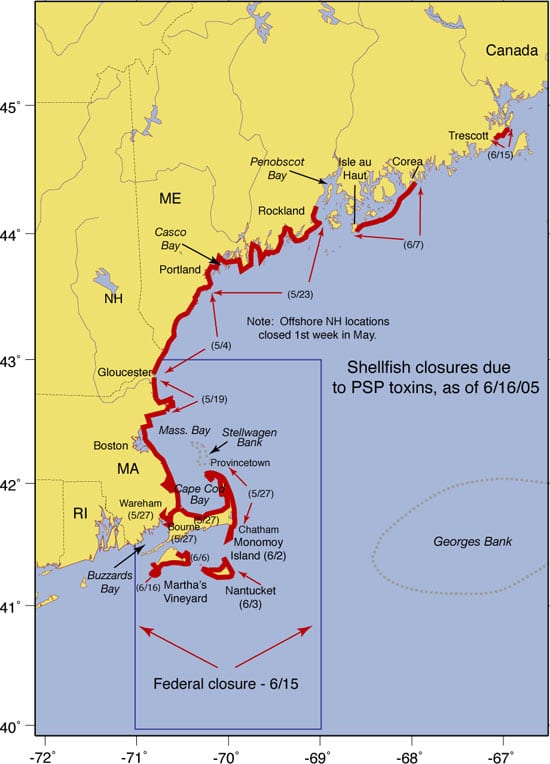

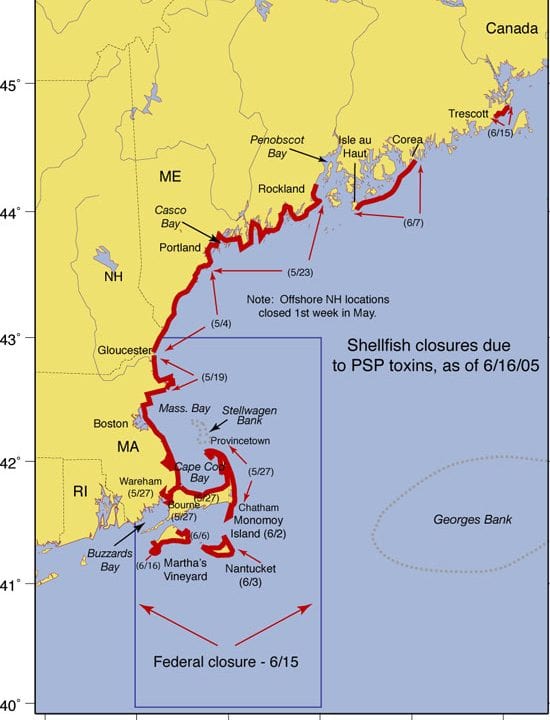

In 2005, concentrations of toxic algae reached levels 40 times the norm, and the plants spread southward to regions of Cape Cod Bay, Massachusetts Bay, Nantucket Sound, and Buzzards Bay that are usually not affected by this species.

Shellfish beds in Massachusetts, Maine, and New Hampshire, as well as 15,000 square miles of federal waters, were closed for more than a month at the peak of the seafood harvesting season. Economists for the shellfish industry and the state of Massachusetts estimated that the bloom cost the seafood industry $2.7 million per week in lost revenues, with some estimates suggesting double that amount. NOAA has declared the event a “commercial fisheries failure,” which may allow fishermen to receive federal emergency assistance.

Partners for safety

Kevin Chu, regional administrator of the NOAA National Marine Fisheries Service, noted that “despite high risks and great levels of concern, no one has been hospitalized” by this year’s bloom, due in part to the timely observations from WHOI, and federal, state, and local research and monitoring agencies.

“WHOI has been essential in helping us determine where and when we should close fisheries, and this collaboration has been a great success,” Chu said. He also commended the Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries for its excellent management of a difficult and potentially disastrous event.

As of July 15, the waters appear to be clearing and shellfish beds are slowly being reopened for harvesting, though federal offshore waters are expected to remain closed until Sept. 30. “We didn’t detect any significant populations last week in the nearshore waters of southern New England,” said Bruce Keafer, a WHOI biological oceanographer. In the Gulf of Maine, the bloom is 50 nautical miles offshore and is no longer flowing into Massachusetts Bay. “It appears to be returning to a more ‘normal’ situation.”

“The major concern now is if Alexandrium will come back,” Keafer added. “A late-season tropical storm could create the northeast wind conditions to start it over again this year. And the cysts dropped during the termination of this bloom are a concern for the ensuing years.”

It ain’t over when it’s over

Keafer and Anderson are working out the logistics for a new cyst survey of New England waters in September and October. They will be remapping areas that they surveyed in the fall of 2004, looking for differences in the number of Alexandrium cysts buried in seafloor sediments. They also will examine whether a seed population has been sown in the waters of Cape Cod Bay or Massachusetts Bay.

Historically, there have been two large beds of cysts in the Gulf of Maine: one located near the Bay of Fundy and the other off Casco Bay, near Portland. It’s not unusual to find millions of cysts per square meter of sediment in these areas, Anderson noted.

“The Massachusetts Bay region contained very few cysts in 2004, but the 2005 bloom may have changed that,” said Keafer. The fall expeditions will determine if the cyst distribution has extended into more southern waters and if it could lead to subsequent outbreaks in those areas, propagating the problem even further south and west.

Following the 1972 Alexandrium bloom, cysts spread into the waters of southern New England. There was no bloom in 1973, but an extensive one developed in 1974 and smaller blooms persisted all the way up to 1993. For the past 12 years, Alexandrium has rarely reached harmful proportions in Massachusetts Bay.

It takes more than just a seed population to cause blooms. Water temperature and nutrients need to be just right to allow Alexandrium to outcompete other microscopic plants in the water. Wind and current patterns may blow future generations of algae out to sea before they can bloom near shellfish beds along the coast. And bottom-dwelling animals may eat or bury the cysts before they can settle to the ocean floor or rise from it again.

It’s possible that the oceanographic conditions this spring favored the bloom of a certain population, or genotype, of Alexandrium this year. WHOI biologist Deana Erdner is leading a laboratory team that is gathering genetic information about the Alexandrium cells from different regions of New England waters to see how their makeup relates to the physical and chemical conditions observed this spring. The researchers are a month or two away from being able to release preliminary results.

Researchers will extend their 10-year effort to determine how weather conditions, nutrients, and currents promote or prevent algal blooms in New England. They also will analyze data from drifters and from weather and water measurements to see if they can replicate with computer models what they observed firsthand.

“I don’t think there is any question that there are cysts here now in southern New England,” said Anderson. “The question is: Will conditions allow them to stay and bloom, or will they wash out?”

Funding for studies of Alexandrium fundyense and the bloom of 2005 has been provided by NOAA’s Center for Sponsored Coastal Ocean Research, the WHOI Coastal Ocean Institute, and the National Science Foundation and National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, which support the Woods Hole Center for Oceans and Human Health. The WHOI research team also thanks its collaborators at the National Marine Fisheries Service, the Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries, the Massachusetts Water Resources Authority, the Provincetown Center for Coastal Studies, the New Hampshire Department of Environmental Services, the Maine Department of Marine Resources, and the Woods Hole field stations of the U.S. Geological Survey and U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

Slideshow

Slideshow

- At the height of the potent 2005 bloom of Alexandrium fundyense, coastal resource managers closed shellfish beds from Maine to Martha?s Vineyard. This map was compiled from information provided by the Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries, the New Hampshire Department of Environmental Services, and the Maine Department of Marine Resources. Individuals should consult local shellfish wardens regarding up-to-date closures.

- From left: physical oceanographer Dennis McGillicuddy, research assistant Kerry Norton, and biological oceanographer Bruce Keafer draw samples from a CTD rosette, which measures conductivity, temperature, and depth while collecting water. During several expeditions on the WHOI coastal vessel Tioga, the researchers examined coastal waters for Alexandrium cells and for the water-borne nutrients that allow them to flourish.

- Research associate Bruce Keafer looks for Alexandrium cells with a microscope during a research cruise on Tioga.

- A computer model shows how the pattern of northeasterly winds?which dominated in spring 2005?can push Alexandrium cells down from the Gulf of Maine into Massachusetts Bay and Cape Cod Bay. In typical years, prevailing breezes from the southwest usually blow the cells out to sea before they can flow into Massachusetts Bay. Reds and oranges show areas of highest concentration. (Don Anderson Laboratory, WHOI)

- Researchers from WHOI use fluorescent microscopy to positively identify and count Alexandrium fundyense cells in the laboratory in Woods Hole. Visual identification of cells was also done under a microscope at sea.

Related Articles

- Busting myths about HABs

- Are warming Alaskan Arctic waters a new toxic algal hotspot?

- Sargassum serendipity

- A dragnet for toxic algae?

- The Recipe for a Harmful Algal Bloom

- As Bay Warms, Harmful Algae Bloom

- Not Just Another Lovely Summer Day on the Water

- Setting a Watchman for Harmful Algal Blooms

- Dropping a Laboratory into the Sea

See Also

- NOAA Center for Sponsored Coastal Ocean Research

- The Harmful Algae Page

- WHOI-Dartmouth model of wind forcing on currents before red tide

- Seeing Red in New England Waters from Oceanus magazine

- Slideshow of WHOI red tide research

- WHOI New England Red Tide Site

- Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries

- Maine Department of Marine Resources

- Woods Hole Center for Oceans & Human Health