On the Trail of Microbes that Cause Seafood Poisoning…

...and other recent fieldwork around the world by WHOI researchers

Did humans kill off ancient wild horses?

WOODS HOLE—Between 10,000 and 20,000 years ago, many large mammals became extinct in North America and around the world. The cause of these extinctions has been hotly debated, with climate change and overhunting by humans as the leading contenders.

In Alaska, the most recent fossil remains of mammoths postdate the arrival of humans across the Bering ice/land bridge into North America around 13,000 years ago, but the most recent remains of wild horses predate human arrival. That supported contentions that while human overhunting could have contributed to the extinction of mammoths, it could not have been a factor in the wild horse’s extinction.

But in the May 9, 2006, issue of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Andy Solow, senior scientist and director of the Marine Policy Center at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, and co-authors David Roberts and Karen Robbirt from the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew, England, showed that uncertainties in the dating of horse fossils are so large that the coexistence of horses and humans cannot be ruled out.

The debate remains open. See On the Pleistocene extinctions of Alaskan mammoths and horses.

Ferry takes on a new task as research vessel

NANTUCKET SOUND—A ferry that provides transportation from Woods Hole to Martha’s Vineyard has added another role as a research vessel. Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution biologist Scott Gallager and colleagues installed a package of sensors on the ferry Katama (right) in May 2006 to measure water temperature and clarity, and oxygen, salinity, and chlorophyll levels, and to photograph plankton as the ferry crisscrosses the western side of Nantucket Sound year-round, several times daily.

With the interest and cooperation of the Steamship Authority, which operates the ferry service between Cape Cod and the islands of Martha’s Vineyard and Nantucket, the WHOI team will install another instrument package on the ferry Eagle, which runs between Hyannis and Nantucket on the eastern side of Nantucket Sound. Their objective of the project, supported by Woods Hole Sea Grant, is to develop a portrait of changing water conditions and plankton communities in the sound. The sensor package can fit in a suitcase and is placed in a cavity in the ship’s hull.

“Hitchhiking science on a ferry provides a terrific opportunity for us to better understand water quality and ocean life change over time,” Gallager said.

Real-time data from his sensors travel over a wireless connection to shore where Gallager and WHOI colleagues Steve Lerner, Emily Miller, and Andy Maffei make them available to scientists and the public on the project website.

Photo by Tom Kleindinst, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution

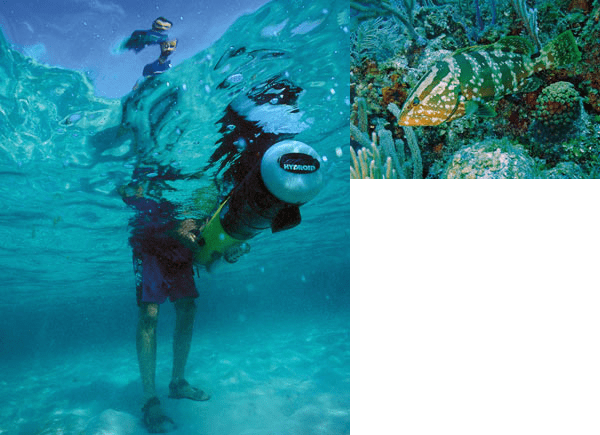

On the trail of microbes that cause seafood poisoning

ST. THOMAS, U.S VIRGIN ISLANDS—Ciguatera fish poisoning—which can cause gastrointestinal, neurological, and cardiovascular problems for humans—is the world’s most common form of illness from fresh seafood. Despite its pervasive impacts on human health and seafood economies, the tropical organisms that cause it have scarcely been studied.

In April 2006, marine biologists Don Anderson of WHOI and Deana Erdner of the University of Texas (a former MIT/WHOI Joint Program Student with Anderson) began fieldwork with chemist Robert Dickey of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to study Gambierdiscus toxicus, the dinoflagellate algae that produces the chemical precursors that are transformed into ciguatoxins in the tissues of edible reef fish.

Funded by the WHOI Ocean Life Institute’s Tropical Research Initiative, the team collected hundreds of samples for a project that will analyze the distribution, population genetics, and toxicity of Gambierdiscus around St. Thomas and St. John in the U.S. Virgin Islands. See Ciguatera Fish Poisoning.

Photo by L. Anderson

She samples cell shells on the seafloor

WESTERN NORTH ATLANTIC—WHOI geobiologist Joan Bernhard was chief scientist aboard R/V Oceanus on a May 2006 cruise near the Bahamas to sample sediment from the sea bottom and collect from it living, single-celled organisms called foraminifera, or “forams,” for short. Most forams make shells whose chemical composition is thought to reflect the characteristics of the seawater surrounding them.

Bernhard and WHOI geochemist Dan McCorkle (at left, processing samples in the onboard refrigerated laboratory), and University of South Carolina (USC) postdoctoral scientist Chris Hintz brought the samples back to WHOI and USC, where they will culture the foraminifera in labs under controlled conditions. Through these efforts, they seek more detailed knowledge of how environmental conditions, such as water temperature and acidity, control the chemistry of foram shells.

The information will improve scientists’ ability to use long-preserved foram shells in oceanic sediments to reconstruct past environmental conditions, enabling better understanding of how and why conditions have changed. See more on Bernhard’s research.

Photo courtesy of Joan Bernhard, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution

Buoy riders

GULF STREAM—Service calls to buoys in the middle of the Gulf Stream are anything but routine. Soon after this buoy was deployed in November 2005 in the Gulf Stream, it was damaged, researchers suspect, by a collision with another ship. (Note the bent beam at the buoy’s top right.)

WHOI scientists tried to make repairs when the WHOI research ship Atlantis was in the vicinity in January 2006, but seas were too rough. But in April, another WHOI research ship, Oceanus, was scheduled to conduct research in the area. It dropped off WHOI engineer Frank Bahr (left) and research specialist Jeff Lord of the WHOI Physical Oceanography Department, who spent several hours bobbing in the ocean, replacing damaged meteorological sensors on the buoy.

The buoy is part of a major study, funded by the National Science Foundation, to make long-term atmospheric and oceanographic measurements in the Gulf Stream, whose warm waters give up their heat to the atmosphere in winter and then become cooler and denser and sink. This critical but little-studied process brings carbon dioxide, nutrients, and heat from the ocean surface to the depths and has significant impacts on climate and marine life. See The Hunt for 18° Water.

Photo by Patrick Rowe, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution

Sunlight neutralizes toxic mercury in lakes

ALASKA—Sunlight triggers chemical reactions that help transport toxic mercury from the atmosphere into rivers, lakes, and the ocean. But a new study also showed for the first time that sunlight decomposes as much as 80 percent of the methylated mercury in Arctic lakes before it gets into fish that humans eat.

The return of the sun after dark Arctic winters oxidizes mercury in the atmosphere into a more reactive form that attaches to rain, snow, or dust and falls into water bodies. However, in their studies of four Alaskan lakes, marine biogeochemists Chad Hammerschmidt of Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution and William Fitzgerald of the University of Connecticut found that sunlight also catalyzes the breakdown of methylmercury, the poisonous form that accumulates in fish flesh.

The scientists noted that global warming could increase precipitation and the decomposition of soil and rocks, sending more mercury, as well as organic debris, into lakes and oceans. The debris would make lakes cloudier, blocking the penetration of sunlight and its potential poison-removing effects.

The scientists reported their findings in the January 2006 issue of Environmental Science and Technology.

Photo by Chad Hammerschmidt, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution

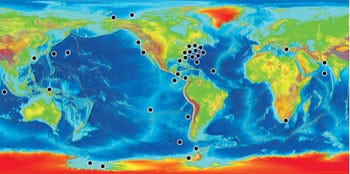

WHOI Around the World

See WHOI Around the World for an interactive map that highlights WHOI research expeditions on land and at sea since 2004.

Grouper dynamics

GLOVER’S REEF, BELIZE—Nassau groupers are large, delicious, and easy to catch when they aggregate by the thousands to spawn on coral reefs in the Caribbean. To protect the species from overfishing, conservationists have proposed setting aside marine preserves, but they don’t know which areas are most critical because they don’t know enough about how the fish travel through the oceans from larval stages to adulthood.

In January 2006, WHOI scientists launched a novel collaborative study, funded by the Oak Foundation, on Glover’s Reef in Belize. To track fish from their birthplaces, biologist Simon Thorrold “tags” fish embryos with a nontoxic chemical marker that can be detected in the fish’s ear bones throughout their lives.

He is working with biologist Jesús Pineda and physical oceanographer Glen Gawarkiewicz, who uses a free-swimming robotic vehicle, REMUS, to obtain detailed measurements of currents that may sweep fish larvae on and off reefs. See the Fish Ecology Lab at WHOI and REMUS.

Photo at right by Simon Thorrold and photo on left by Chris Linder, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution

A cryological journey

ICELAND—MIT/WHOI graduate students and faculty explored a bubbling, sulfur-encrusted hot spring in June 2006 on a field trip to Iceland. The trip capped WHOI’s Geodynamics Program, an annual semester of weekly seminars, given by scientists invited from many research institutions, on cutting-edge research on a particular earth sciences field. This year’s program focused on all things cryological: ice sheets, glaciers, sea ice, and subglacial life.

The Geodynamics Program was started by WHOI scientists Henry Dick, Jack Whitehead, and Hans Schouten in the early 1980s with funding from the Keck Foundation to promote interdisciplinary research. Past year’s programs have explored the frontiers of research about the early Earth, fluid flow within the Earth, and catastrophic events, such as earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, landslides, and hurricanes. Program sponsors now include the WHOI Academic Programs Office and the Deep Ocean Exploration Institute.

Photo by Chris Linder, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution

Related Articles

- Behind the blast

- Seeding the future

- Cold, quiet, and carbon-rich: Investigating winter wetlands

- Sonic Sharks

- A rare black seadevil anglerfish sees the light

- How will we ever count them all?

- Five marine animals that call shipwrecks home

- Deep-sea amphipod name inspired by literary masterpiece

- The case for preserving deep-sea biodiversity