New Sonar Method Offers Window into Squid Nurseries

Technique provides a way to monitor the health of squid fisheries

Every spring the swallows return to Capistrano, and farther up the California coast, hordes of squid arrive to mate and lay eggs on the sandy seafloor off Monterey. Right on their tentacles are fishermen seeking calamari.

California’s $30-million-a-year squid fishery has quadrupled in the past decade—with no way to assess how much fishing is too much. Now, a multi-institutional team of scientists has reported a new sonar technique to locate squid eggs in the murky depths.

“This method provides an efficient way to map distributions and estimate the abundance of squid eggs. In effect, it censuses next year’s potential population,” said Kenneth G. Foote, a marine acoustics expert at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution and lead author of an article published in the February 2006 Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. “It has immediate potential to give resource managers sound scientific information to make decisions on how to sustain the fishery. Otherwise, they’re just guessing.”

The scientific team combined the expertise of Foote; Roger T. Hanlon from Marine Biological Laboratory in Woods Hole, an authority on squid behavior; and Pat J. Iampietro and Rikk G. Kvitek, seafloor mapping experts at California State University Monterey Bay (CSUMB). The research was funded by the Sea Grant Essential Fish Habitat Program.

Mops and clusters

Squid (Loligo opalescens)—a staple in the diets of many fish, birds, and marine mammals—return annually to spawn a few hundred yards off Monterey’s Cannery Row. They deposit gelatinous capsules, each containing 150 to 300 embryos. The finger-sized capsules form small clumps called mops that later cluster into egg beds up to several meters in diameter. Surveying the four-square-mile spawning grounds with divers or underwater cameras is too difficult, time-consuming, and expensive.

“We needed a way to detect egg clusters,” Hanlon said. “So I went across the street and approached Ken, one of the world’s sonar experts, who said, ‘I’ll see if I can help you.’ ”

“I wasn’t optimistic,” Foote said. “You have to be able to distinguish weak signals echoing off small targets—the egg clusters—from powerful signals echoing off much larger targets—the seafloor.”

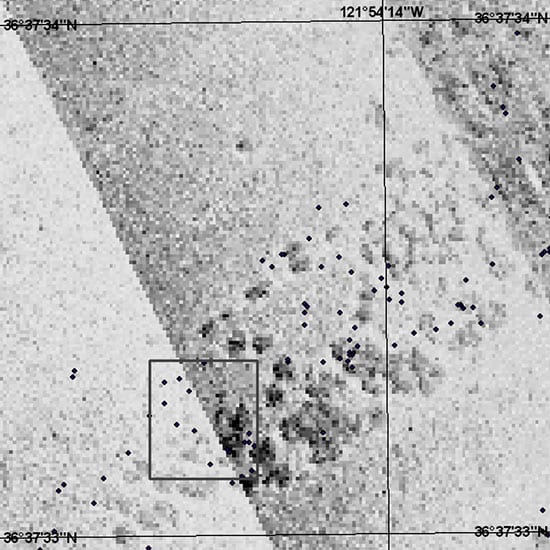

The team tested different sound wave frequencies, sonar angles, and towing speeds and heights off the seafloor—all in an effort to optimize sound signals reflected back from the egg clusters. They processed the raw acoustic data and displayed the results in the form of seafloor maps that showed characteristic patterns of mottling—squid egg clusters—distributed on the seafloor images. Using underwater video and the CSUMB ship’s precise positioning capabilities, they verified the correlation between sonar images and egg clusters.

Squid’s complex sex life

With the new sonar methods, the entire Monterey spawning area could be surveyed and analyzed in less than 40 hours at relatively low cost, with a suitably equipped boat towing a sidescan sonar, Foote said.

Since fishing usually commences as soon as squid appear in Monterey Bay, Hanlon said, fishermen may be catching large numbers of squid before they can complete their complex and competitive mating behaviors and subsequently lay eggs.

“The next challenge is to convince the fishermen to wait a few days for squid to complete their mating cycle,” Hanlon said, “so that gene mixing in the population will proceed by natural, not unnatural, selection processes. The squid need to lay enough eggs to provide squid next year—for fishermen and for the oceans, too.”

Foote and Hanlon said the sonar techniques could be adapted and applied to more effectively manage other squid fisheries around the world, including major fisheries in South Africa, Japan, the Falkland Islands, southern California, and perhaps on the United States East Coast.

Slideshow

Slideshow

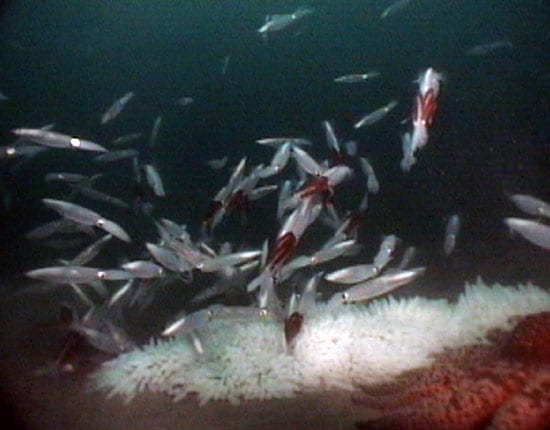

Hordes of squid return each spring to waters off Monterey, Calif., to spawn and lay eggs. Fishermen may be catching large numbers of squid before they can complete their complex and competitive mating behaviors and subsequently lay eggs. (Courtesy of Roger T. Hanlon, Marine Biological Laboratory)

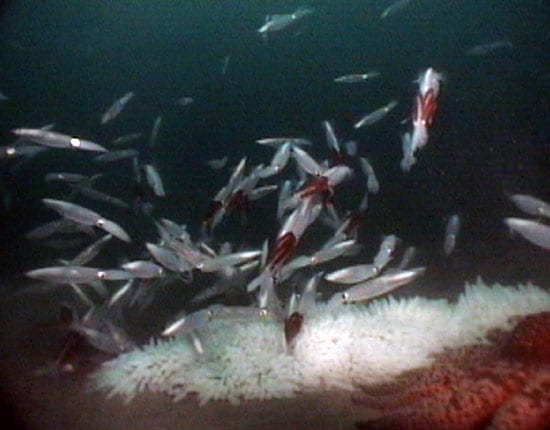

Hordes of squid return each spring to waters off Monterey, Calif., to spawn and lay eggs. Fishermen may be catching large numbers of squid before they can complete their complex and competitive mating behaviors and subsequently lay eggs. (Courtesy of Roger T. Hanlon, Marine Biological Laboratory)- Squid (Loligo opalescens)are a staple in the diets of many fish, birds, and marine mammals. They return annually to spawn a few hundred yards off Monterey?s Cannery Row (Courtesy of Roger T. Hanlon, Marine Biological Laboratory)

- Squid deposit gelatinous capsules, each containing 150 to 300 embryos. The finger-sized capsules form small clumps called mops that later cluster into egg beds up to several meters in diameter. (Courtesy of Roger T. Hanlon, Marine Biological Laboratory)

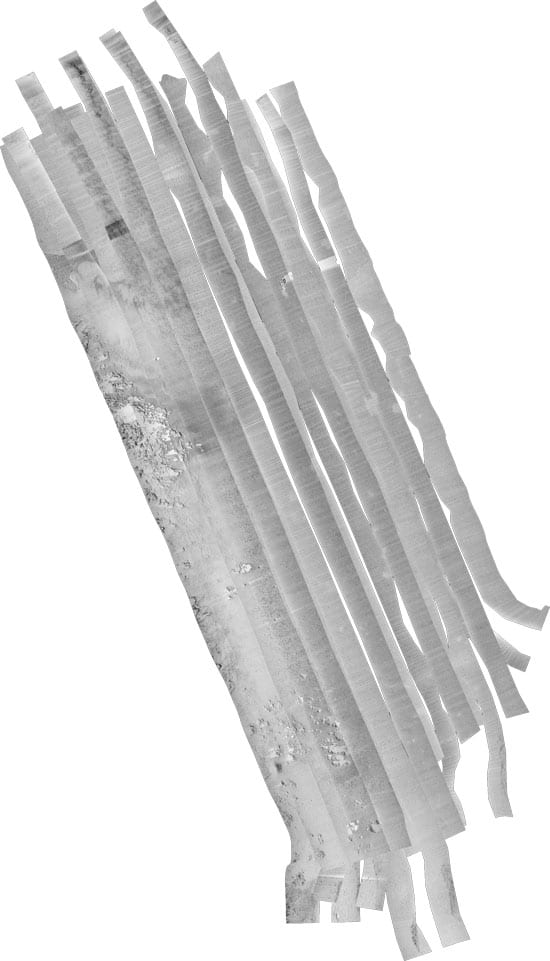

- Strips of sonar images are mosaicked together to create a composite map of the seafloor off Monterey, Calif., where squid gather each spring to spawn. (Courtesy of Kenneth G. Foote, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

- The sonar map reveals a mottled pattern that represents squid egg clusters, giving scientists a way to census next year?s potential squid population. (Courtesy of Kenneth G. Foote, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

Related Articles

- How WHOI helped win World War II

- Learning to see through cloudy waters

- A curious robot is poised to rapidly expand reef research

- Whale Safe

- Measuring the great migration

- WHOI breaks in new research facility with MURAL Hack-A-Thon

- Bioacoustic alarms are sounding on Cape Cod

- A tunnel to the Twilight Zone

- The Deep-See Peers into the Depths

Topics

Featured Researchers

See Also

- Acoustic detection and quantification of benthic egg beds of the squid Loligo opalescens in Monterey Bay, California Article in the Journal of the Acoustical Society of America

- Kenneth G. Foote

- Seafloor Mapping Lab at California State University, Monterey Bay