Jason Meets the Carnivorous Sea Squirt

Expedition to the Tasman Fracture finds unknown species

Tito Collasius, an engineer at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, has witnessed some of oceanography’s more celebrated moments, including the discovery of the Titanic and the eruption of undersea volcanoes. But on expedition south of Tasmania that ended in January 2009, what caught his breath was a quiet field of rainbow-hued anemones, crabs, sea stars, sponges, and corals.

Collasius guided the remotely operated vehicle Jason in the Tasman Fracture, a trench that drops nearly three miles below the surface of the Southern Ocean. He recalled sitting with scientists on board the research vessel Thomas G. Thompson and staring mesmerized at computer screens playing Jason’s live video, sent via a cable from the seafloor.

“At one point, we were exploring a seamount that had not been topped by fishing trawlers,” he said. “The biology was unbelievable, with purple corals and vibrant orange spider crabs. It was like a bouquet.”

“It was truly one of those transcendent moments,” said the cruise’s lead scientist, Jess Adkins of the California Institute of Technology. “We were flying—literally flying—over these deep-sea structures that look like English gardens, but are actually filled with all of these carnivorous, Seuss-like creatures that no one else has ever seen.”

The translucent creature was a sea squirt, an animal that usually feeds by pushing seawater through is body and filtering out plankton. This one, however, has a funnel-shaped head triggered to close when shrimp and other prey entered—much the way a Venus flytrap feeds.

The scientists also discovered a new species—possibly an entirely new family—of barnacles and a new species of sea anemone. The latter was a mixed blessing because, unfortunately, it mimicked the appearance of the primary target that the scientists were looking for: deep-sea corals.

As they grow, these long-lived corals build skeletons that incorporate telltale chemical clues from surrounding seawater, which allow scientists like Adkins to reconstruct how ocean and climate conditions have changed over Earth’s history (see The Coral-Climate Connection). Australian and American biologists directed Collasius and the Jason team to collect hundreds of samples, both live and fossilized.

Until this voyage, the Tasman Fracture had only been explored to a depth of 1,800 meters (more than 5,900 feet). Using Jason, the researchers on this trip were able to reach as far down as 4,000 meters (more than 13,000 feet).

“We set out to search for life deeper than any previous voyage in Australian waters,” said Ron Thresher, a scientist from Australia’s Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO).

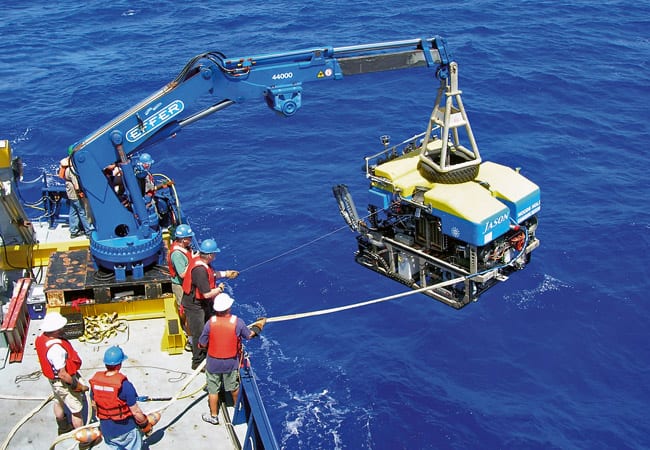

On April 3, Collasius and Jason returned to an undersea volcano near the Mariana Islands northwest of Guam, where Jason helped scientists observe a deep-ocean eruption live for the first time in 2004, and again in 2006 (see Jason Versus the Volcano). Sensors left near the site indicated that the volcano, called Northwest Rota-1, still showed signs of activity. When they arrived, they found that it was still erupting.

During the expedition, the science team reported its findings on a blog (http://nwrota2009.blogspot.com/)

The Tasman Fracture research was funded by the National Science Foundation, CSIRO, the Commonwealth Environmental Research Facilities’ Marine Biodiversity Hub, and the Australian Department of the Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts.

Slideshow

Slideshow

- Images captured by the remotely operated vehicle Jason revealed several previously unknown species during a recent expedition to the Tasman Fracture, south of Australia, including this translucent, 1.6 foot (half-meter) tall carnivorous sea squirt. It traps prey in its funnel-shaped head. (Advanced Imaging and Visualization Laboratory, WHOI/Jess Adkins, Caltech)

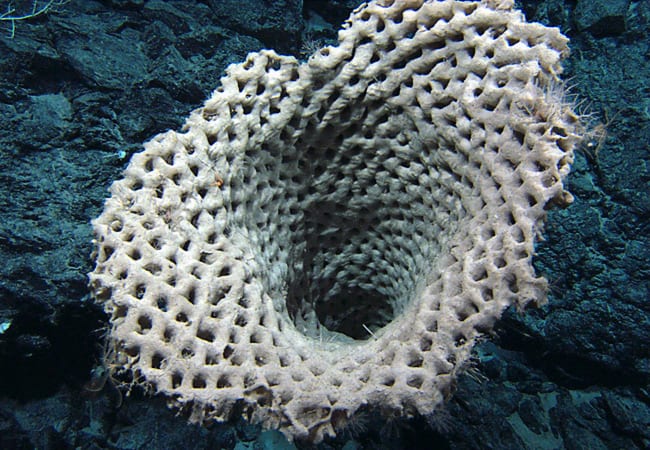

- Another new species discovered on the Tasman Fracture expedition was this "waffle cone" sponge, 1.6 feet (50 centimeters) wide and 6.5 feet (200 centimeters) tall. (Advanced Imaging and Visualization Laboratory, WHOI/Jess Adkins, Caltech)

- This newly discovered species of soft coral, called a gorgon's head coral, was found using the remotely operated vehicle Jason during a December 2008-January 2009 expedition off Tasmania, Australia. (Advanced Imaging and Visualization Laboratory, WHOI/Jess Adkins, Caltech)

- Using Jason, researchers were able to reach as far down as 4,000 meters (more than 13,000 feet) into the Tasman Fracture, a deep trench in Australia's 42,500-square-kilometer (16,400-square-mile) Tasman Fracture Commonwealth Marine Reserve.

(Map courtesy of Department of the Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts, Commonwealth of Australia) - The remotely operated vehicle Jason is lowered in 2006 to explore an erupting underwater volcano near the Marianas Islands in the Pacific Ocean. The deep-sea explorer returned to the site in April 2009. (Photo by Tom Bolmer, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

Related Articles

Featured Researchers

See Also

- Jess Adkins

- The Coral-Climate Connection from Oceanus magazine

- The Remotely Operated Vehicle Jason

- Jason Versus the Volcano from Oceanus magazine

- Australian Commonwealth Scientific and Research Organization (CSIRO)

- What Other Tales Can Coral Skeletons Tell? from Oceanus magazine

- Coral Gardens in Dark Depths from Oceanus magazine