Going for the GUSTO (Mooring)

WHOI engineers and the Oceanus crew rescue a wounded buoy

It was the oceanographic equivalent of stopping for milk on the way home. Two years ago, Mike McCartney had left a mooring in the Gulf Stream, rigged with sensors to monitor the huge, eastward-flowing current. Last October, Bob Weller—McCartney’s colleague down the hall at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution—and his team were aboard the research vessel Oceanuson their way to do mooring work not too far from McCartney’s mooring.

So while Weller was in the neighborhood, could he do McCartney a favor and pick up his mooring?

“It should have been a breeze to collect mine as well,” McCartney said.

The mooring, known as GUSTO (for Gulf Stream Transport Observations), was anchored to the seafloor by a 2½-ton weight, about 245 nautical miles (450 kilometers) south of Cape Cod. It consisted of a 2½-mile-long wire studded intermittently with eight steel-gray current meters and other sensors that recorded changes in the Gulf Stream’s flow. Attached near each instrument was a small cluster of floats—two to four glass balls encased in banana-colored plastic containers resembling hard hats. These helped the mooring float upward in the strong current like an unclasped necklace.

Atop the line and about 1,312 feet (400 meters) beneath the sea surface was an orange sphere, 64 inches (1.62 meters) in diameter. It was the principal buoy holding the mooring upright; McCartney jokingly called it the Hope Diamond. All the ship’s crew had to do was send a sound signal to release the mooring from its anchor and wait about 10 minutes for the Hope Diamond to float to the surface.

Pinging for answers

As the October sky lightened around 5:50 a.m., a dozen scientists, engineers, and Oceanus crew leaned on the deck rails watching the choppy water for signs of the mooring’s yellow and orange floats. Three hours later, nothing had appeared. Weller, WHOI engineers Jeff Lord and Scott Worrilow, and the crew had no way of knowing that the orange sphere—McCartney’s Hope Diamond—had broken down, leaving the wounded mooring slumped over and sagging.

Weller, the expedition’s chief scientist, encouraged the team to try to retrieve it. But he gave a deadline of 16 hours before they would need to head for the next stop—with or without the mooring—where the ship was needed to recover another moored buoy before it headed for port.

The first thing to do was figure out exactly where the mooring was. The acoustic release mechanism helped them get started. By pinging on it with a sound signal, the team knew that the mooring had released from its anchor, and the release mechanism near the anchor was stuck about 2,400 feet (750 meters) below the surface. The rest of the mooring line was suspended by clusters of buoyant glass balls that backed up the 64-inch Hope Diamond sphere, with the line gradually arcing downward.

In similar circumstances, they have simply dragged the ocean bottom to nab downed moorings. But a map of the area showed a major undersea communications cable connecting North America to eastern continents.

“Not exactly something you want to mess around with,” Lord said.

An improvised Plan B

Engineers and crew spent the better part of the morning and early afternoon assessing the situation and considering novel ways to retrieve the mooring before coming up with an unconventional plan: to snag the mooring while it was suspended in the ocean.

They searched through their onboard mooring recovery supplies and put together a 3,500-meter-long line (nearly two miles in length), made of wire, polypropylene rope, floats to keep it buoyant, and several metal, four-pronged hooks with rounded edges to keep them from cutting the mooring’s wire.

As the team put together the line, WHOI postdoctoral student Tom Farrar developed a computerized display that summarized the results of hours of acoustic ranging on the acoustic release. His work showed the location (in latitude, longitude, and depth) of the acoustic release. This information was critical to avoid trolling too deep and inadvertently snagging the submarine cable.

A jury-rigged lasso

The researchers attached their improvised dragging system to a winch on Oceanus and plotted a course to make the Gulf Stream’s powerful current work for, rather than against, them.

Pulling the dragging equipment behind Oceanus, they motored 650 feet (200 meters) southwest of the GUSTO mooring’s suspected location. They steamed further upstream against the Gulf Stream and turned right, steaming 1,312 feet (400 meters) across the Gulf Stream. Then they turned right again to let the Gulf Stream carry the ship and dragging line downstream, before making a final loop to close the noose around the mooring.

Ship handling was critical, Weller said. Motoring too fast would pull the dragging system up to the surface, above the GUSTO mooring. Going too slow would make it challenging to maintain the desired course in the powerful current.

As the ship finished the pattern, team members continued to ping GUSTO’s acoustic release and watched their computer screens showing its location. They saw that it was moving, as if being towed behind Oceanus, about 1,500 feet (457 meters) from the ship and closing in fast. WhileCapt. Larry Bearse kept the ship steady, they used one of the ship’s winches to wind GUSTO in.

Hope rises then sinks

It was midnight before the first instrument was taken out of the ocean, and the team began noting where the mooring had failed. A number of flotation balls had imploded and shredded the yellow “hard hats”—not an uncommon occurrence on moorings.

What they didn’t expect to see was McCartney’s Hope Diamond. They had surmised that the mooring had trouble surfacing because the big top float had come off. But there it was. Engineers and crew aboard Oceanus could see that the sphere was sheared in several sections, though they only got only a glimpse of it. The heaving sea and increasing tension on the mooring line wire caused it to snap suddenly. The heavy float, now saturated with water, broke free. It sank fast.

Later, McCartney speculated that the sphere, made from chunks of foam glued together, had voids between some of the chunks. Because the strong Gulf Stream current caused the mooring to constantly tilt over in the ocean, the sphere was pushed over like a palm tree in a hurricane from its normal depth of 1,300 feet (400 meters) down to 3,280 feet (1,000 meters). The deeper depth exerted more pressure on the foam, crushing it, causing the glue to break apart, and the foam to float away. Without this buoyancy, the float was transformed into an anchor.

Hope sinks then rises

McCartney was sailing his schooner North Star near Port Clyde in Maine when he learned via cell phone that he was in danger of losing his mooring. “At precisely the point when Scott was telling me about the GUSTO mooring being hung up at mid-depth, I bounced my iron keel off an uncharted cluster of rocks,” he said. McCartney called back to learn that the mooring was retrieved, along with all its instruments.

Given the circumstances, “they could have abandoned it—just said ‘Well, it’s your problem now,’ ” McCartney said. “What they did was quite remarkable.”

McCartney was able to download nearly a year’s worth of irreplaceable data on the Gulf Stream, which plays an important role in transferring tropical heat into the northern North Atlantic and hence has large impacts on the climate in the North Atlantic region. He will compare the data with some that researchers collected in the same area in the 1980s. As Earth continues to show signs of a warming climate, McCartney wants to know how the changing climate has affected the Gulf Stream, and vice versa.

“We’re talking about some potentially big changes in the ocean circulation system,” he said. That could mean shifting climate patterns in North America and Europe.

Bob Weller’s cruise was supported by WHOI Access to the Sea funds. Mike McCartney’s GUSTO mooring was funded by the Ocean and Climate Change Institute at WHOI.

Slideshow

Slideshow

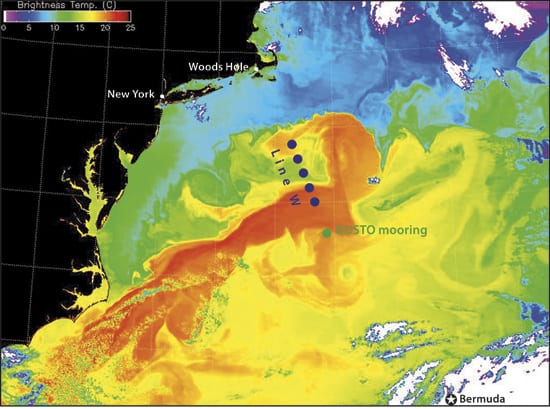

- The GUSTO mooring was anchored to the seafloor about 245 nautical miles (450 kilometers) south of Cape Cod in the Gulf Stream, a powerful current of warm ocean water that flows along the east coast of the United States and Canada and influences climate in the North Atlantic region. It aligned with another WHOI array of moored instruments called Line W (see "Will the Ocean Circulation Be Unbroken?").

- The mooring's precarious position required use of 3,500-meter-long line (nearly two miles in length) that engineers designed, on the spot, specifically for this unique mooring recovery. They crafted their line from wire, polypropylene rope, floats to keep it buoyant, and several metal, four-pronged hooks (above Jeff Lord's hand, on left) with rounded edges to keep them from cutting the mooring?s wire. (Photo by Trish White, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

- Engineer Jeff Lord (left), working with an Oceanus crew member, called the recovery of the mooring unlike anything he'd experienced in 10 years of mooring work. After one loop with the ship around the downed mooring, they were able to snag it using a grappling hook like this one. (Photo by Trish White, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

- With his mooring recovered, scientist Mike McCartney was able to download nearly a year?s worth of irreplaceable data on the Gulf Stream. He will compare the data with some that researchers collected in the same area in the 1980s. (Photo courtesy of Mike McCartney, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)