Experts gather to discuss the ocean’s super-powered carbon pump

Morss Colloquium focuses on the ocean’s role in moving carbon out of the atmosphere and into the depths

Estimated reading time: 4 minutes

As a tropical storm threatened coastal New England on the evening of Sept. 15, 2023, hundreds of people gathered at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI), and on-line, to hear experts in science and policy discuss the biological carbon pump, a naturally occurring mechanism in the ocean considered vital to mitigating the climate crisis.

“Wherever you live, you open a newspaper and read that someone is experiencing some consequence of climate change,” said Dr. Deborah Steinberg, a professor at the Virginia Institute of Marine Science and one of the event’s four panelists. The event – the Morss Colloquium, supported by the Elizabeth W. and Henry A. Morss Jr. Colloquia Endowed Fund – was hosted by WHOI’s Ocean Twilight Zone project.

Noting that more intense tropical storms are a consequence of a warming climate, Steinberg said “it’s on us to look long and hard and answer questions, get the science, get the research, and in multiple ways move this issue forward.”

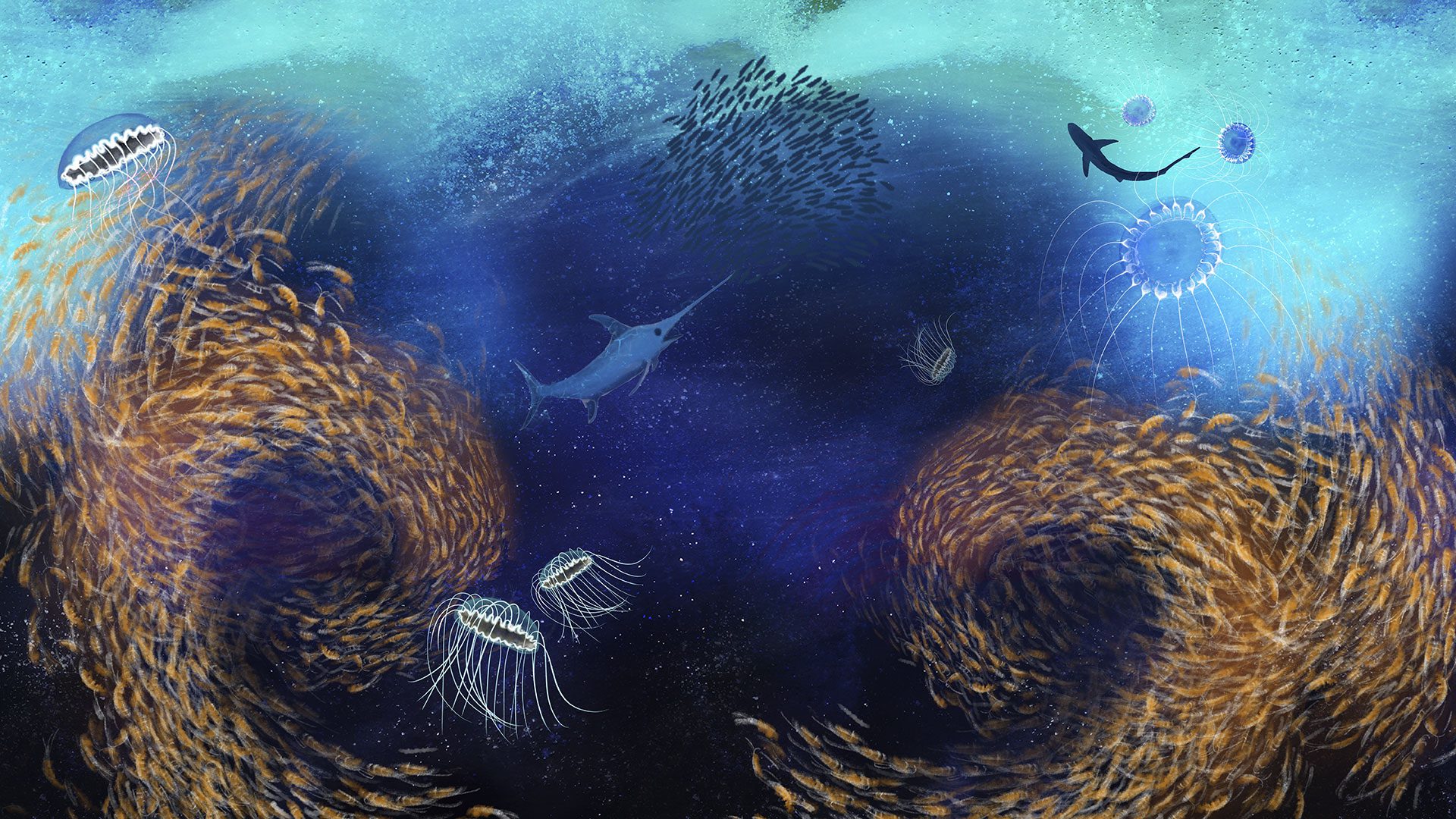

As humans produce emissions that heat the planet, the ocean’s biological carbon pump helps by transferring carbon out of the atmosphere to the ocean where it can be stored for centuries to millennia. Much of this happens in a vast, shadowy region called the ocean twilight zone (also known as the mesopelagic zone), which extends out of sunlight’s penetrating range to depths of about 3,200 feet (1,000 meters).

Scientists know that the ocean twilight zone contains possibly the world’s largest and least exploited fish stock, supports a massive daily migration of marine life traveling from depth to surface waters to feed before heading to depth again, and that it recycles about 80 percent of organic material that sinks from the productive surface waters.

Called “marine snow,” this blizzard of carbon-rich material from the byproducts of plankton, fish, and other animals sinks and becomes food for a wide range of other organisms, from spiky-toothed bristlemouth fish and eels to squid and bioluminescent jellyfish, all a foundation of the marine food web.

“We love these weird and wonderful creatures,” noted filmmaker and ocean explorer James Cameron in a recorded video shown preceding the panelists remarks. “They’re climate heroes living in a region that is sequestering at least as much carbon each year as emitted by all the world’s automobiles.” That number is estimated at two to six billion tons of carbon annually.

Morss Colloquium moderator Dr. Kilaparti Ramakrishna, interim Director of the Marine Policy Center at WHOI, next introduced two presenters who work in international policy development. Ambassador Peter Thomson, United Nations Special Envoy for the Ocean, spoke from Fiji via a recorded video, followed by panelist Kristina Gjerde, the high seas policy advisor for the International Union for Conservation of Nature Global Marine and Polar Program. Gierde spoke on the positive implications of a new United Nations treaty on the high seas that, if ratified, will establish an integrated approach to ocean management in the seas beyond national borders, including in the ocean twilight zone.

Panelist Kakani Katija, a principal engineer at the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute in California, described how technologies like autonomous platforms, robotic vehicles, and sensors are used to investigate the ocean twilight zone, and how they can be implemented more pervasively and affordably.

“Some parts of the ocean can reach up to 11,000 meters depth (nearly 7 miles), so imagine trying to do observations in a place this massive,” she said. “We probably only observe about one percent of it with human eyes or proxies, like imaging. We have gaps that we need to understand.”

Panelist Dr. Ken Buesseler, a marine radiochemist at WHOI, described other atmospheric carbon removal techniques, such as ocean iron fertilization to increase the ocean’s ability to store carbon. Adding small amounts of iron to the ocean’s surface can trigger phytoplankton blooms that remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere.

“There’s no silver bullet here,” Buesseler said. “We’re going to need lots of solutions at the same time to make a dent on the scale of multiple billions of tons of carbon emissions. The question is, can we do that in a responsible way?”

During the open forum and in closing remarks, panelists advised on the immediate and ongoing steps that can be taken on the issue of carbon emissions: vote for politicians who support the reduction and elimination of carbon emissions; involve the public while continuing broad education on the issue; and fund more science while also supporting business and technology opportunities to reduce carbon emissions.

“There are multiple pathways towards a future that is either sustainable or unsustainable, or sustainable for some and unsustainable for many,” Steinberg said. “We have to choose now what future we prefer and take action accordingly.”