Grits, storms, and cosmic patience

As storms stall liftoff, Europa Clipper Mission Team member Elizabeth Spiers patiently awaits the biggest mission of her life

Estimated reading time: 5 minutes

The Waffle House never closes.

Or so Elizabeth Spiers thought.

The 29-year-old space scientist stares down into her plate of over-easy eggs, toast, and grits—the southern staple she developed a taste for as a graduate student at the Georgia Institute of Technology in Atlanta. There, she studied ocean worlds before working for NASA and more recently, joined WHOI as a post-doc to study the ocean here on Earth.

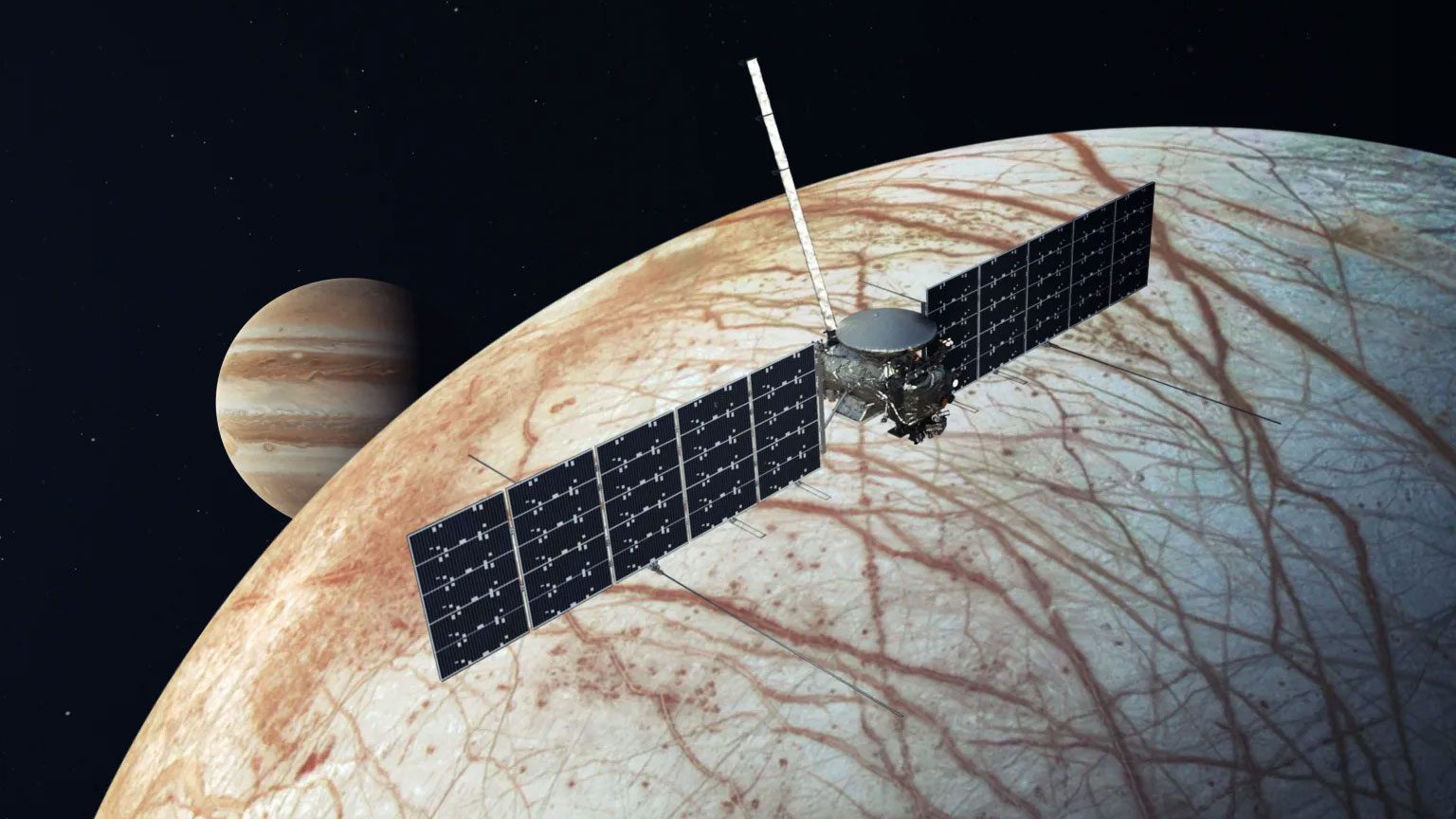

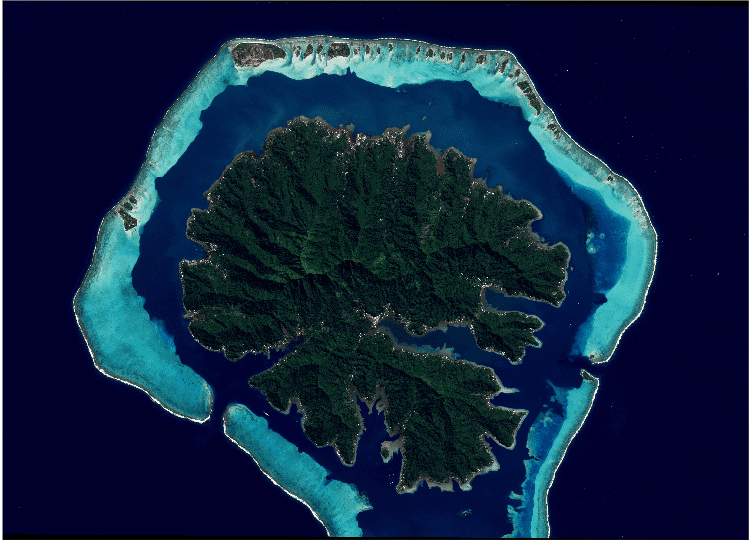

It's mid-October, 2024. Spiers is in Cocoa Beach, Florida for the launch of the Europa Clipper, an event that will kick off a muti-billion-dollar, 10-year NASA mission dedicated to studying Jupiter’s icy moon, Europa, for habitability and the possibility of life. It’s part of a larger effort by NASA aimed at looking for evidence of life beyond Earth within the current human generation.

The question of whether life exists beyond our solar system is one that Spiers grapples with both professionally and personally. Why is there such a gap between Earth, a planet flourishing with so much life, and everywhere else, she wonders. Why are we so special?

Spiers is not in town to simply witness the launch; she’s a member of the Europa Clipper Mission Team. She’s one of around 20 scientists helping to develop models for interpreting the ice-penetration radar data coming back from the spacecraft. The hope is that the data will enable scientists to map the internal structure of Europa’s 10-mile-thick ice cap, which was discovered during NASA’s Galileo Mission in 1989, and understand a lot more about its liquid saltwater ocean below.

Spiers cannot wait to sit in the bleachers at Kennedy Space Center and watch the non-crewed Clipper blast off. She had flown into Orlando on Sunday, expecting the launch to be happening on Wednesday. But that was before Milton came knocking.

Hurricane Milton—the most intense hurricane ever recorded over the Gulf of America—had forced NASA to delay the launch until the following Sunday, despite the fact that the storm had made landfall on the other side of the state. The delay is a huge let down for Spiers. Even worse, all the restaurants in town are closed.

Except for the Waffle House. She tells one of the two colleagues she’s lunching with, who had never dined at a Waffle House before, how the restaurant is considered a safe haven in some communities since it’s always open. It doesn’t matter, she says, whether it’s a family grabbing a bite on a Sunday after church, a college kid stumbling in at 2 a.m., or a hospital worker who just got off their 12-hour shift. The Waffle House, she explains, is always open to everyone.

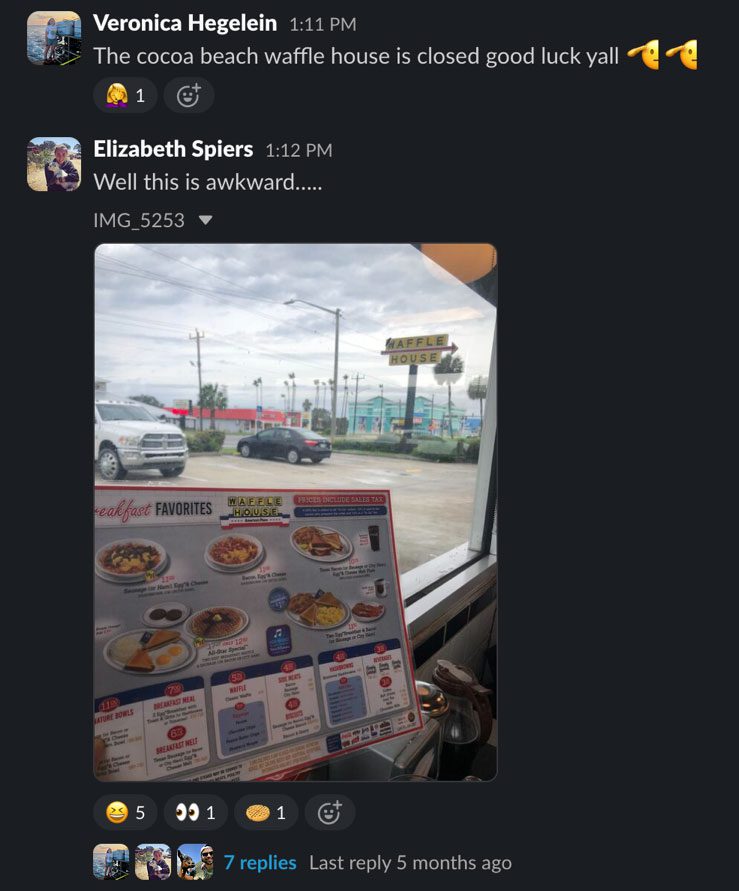

Just then, a Slack message pings her phone. It’s from someone in her PhD lab group saying that the Waffle House in Cocoa Beach is closed.

Closed? Nope, can’t be, Spiers thinks. After all, she’s sitting right here eating grits. Enjoying them, too. She holds the menu in front of her, snaps a picture, and sends it back to her lab mate.

A text exchange between Spiers and her lab mate during Hurricane Milton. (Image courtesy of Elizabeth Spiers)

A few minutes later, a customer walks in the staff is already cleaning up tables and closing down the kitchen. He’s turned away. So they are closing, Spiers realizes.

She knows that if and when a Waffle House does close, it’s usually not a good sign. The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) even has something known as the “Waffle House Index,” a metric that communities use to determine the severity of a storm and how much disaster recovery assistance is likely to be needed.

The restaurant may have stayed open if not for tornado warnings in the area before Milton arrived. A tornado with 90-mile-per-hour winds had already ripped the roof right off a Wells Fargo bank across from the hotel and damaged a carport on the condo building next door, leaving chunks of metal strewn about the property. From the hotel, Spiers watched the intense rain beating against the windows—sideways—like a high-powered carwash.

She gets back to her grits and toast. With the Clipper launch now several days away, she’s hardly in a rush. In fact, she’ll have a lot of time to think about what she’ll be doing on the ground once Clipper’s hurling through space towards Jupiter.

It’s all about being able to make meaningful use of the radar data, she says. Once Clipper begins orbiting Jupiter, it'll make a number of flybys of Europa to measure its interior, its composition, and its geology using an array of sensors, cameras, and IR and UV light spectrometers. The flybys will be quick since the radiation levels around Europa are intense and could easily fry the spacecraft if it hangs around, say, more than a few minutes.

When the signals come back to Earth, they’ll feed models that interpret the information and help answer questions like what the surface composition is like, what is the structure of the ice shell, how salty the water is, how the ocean currents there move, and whether there’s any sign of hydrothermal vent systems on the planet, similar to those on Earth.

Spiers and her team will also try to help answer a set of more overarching questions: Is Europa habitable? And could life exist and thrive in the deep ocean that hides beneath its icy shell?

The answers will all take time, and lots of it. Even at 14 miles per second, Clipper won’t get to Europa for another five years. By the time the bulk of the measurement data is received, Spiers will likely already be a mid-career scientist. But like many planetary scientists, whose projects often run on decadal timescales versus weeks or months, she’s used to waiting for big things to happen.

Spiers and her colleagues finish up their meals. They get the bill, tip the servers generously, and wish them good luck with the storm. She jokes with her colleague that the Waffle House closing on his first visit was a monumental occasion since it really never does.

She hears the restaurant door lock behind her as she starts walking back down North Atlantic Ave. through the drizzling rain. Trucks loaded with sandbags drive by as she passes a Publix supermarket, a Dollar Tree store, and scattered condo complexes where people are moving planters and loose pieces of furniture inside. Lying just a tiny bit further south is her hotel, where she’ll patiently wait for the biggest mission of her life.