For Cynthia Becker, solutions to coral health are in the smallest details

MIT-WHOI Joint Program student Cynthia Becker sits down with Oceanus Magazine to explain why marine microbes may be the key to diagnosing reef health

This article printed in Oceanus Summer 2022

This article printed in Oceanus Summer 2022

Estimated reading time: 3 minutes

Oceanus: What can microbes tell us about coral reef health?

Becker: Just like in our human bodies, the seawater around coral reefs has a range of microbes. These are good, bad, and neutral bacteria that can tell us a lot about a coral reef. As a part of the stony coral tissue loss disease research team in the U.S. Virgin Islands, I'm trying to identify the broad bioindicators for that particular illness. Since 2016, we've been sampling the seawater there to try and understand how the microbial community in the seawater is shifting over time. In addition, we're monitoring changes to every aspect of the reef, from the fish communities to the types of corals currently thriving or suffering. What's been exciting so far is, in some cases, we see the same bacterial clues in our diseased samples from the U.S. Virgin Islands, as we do in the Florida disease samples from reefs much farther away. We're not yet sure if bacteria transmit the disease, but we do know that some appear when corals might be weak and susceptible to illness. A great goal in the future would be to have a database of microbes that are seen around healthy reefs as well those associated with reefs that are weak or in decline. That might help Caribbean officials diagnose a reef in crisis. But it's still early days.

Oceanus: When you're not being interviewed, how do you communicate the importance of coral health to the public?

Becker: I really love outreach. I grew up in the middle of upstate New York, surrounded by lakes, but I was lucky enough to go with my family on vacations to Maine, where I got some exposure to the ocean. Not everybody has that opportunity. We certainly didn't have coral reef lessons when I was in high school, much less in elementary school. So, I've been partnering with fellow coral scientist Laura Weber and marine chemist Kalina Grabb to educate students on the importance of coral reefs. Before the pandemic, we hosted local high school students from Cape Cod, as well as middle school students from New Bedford, Massachusetts, at WHOI and had them build coral reefs out of clay. I've even been able to do virtual lectures with a small school called Greens Farms Academy in Connecticut.

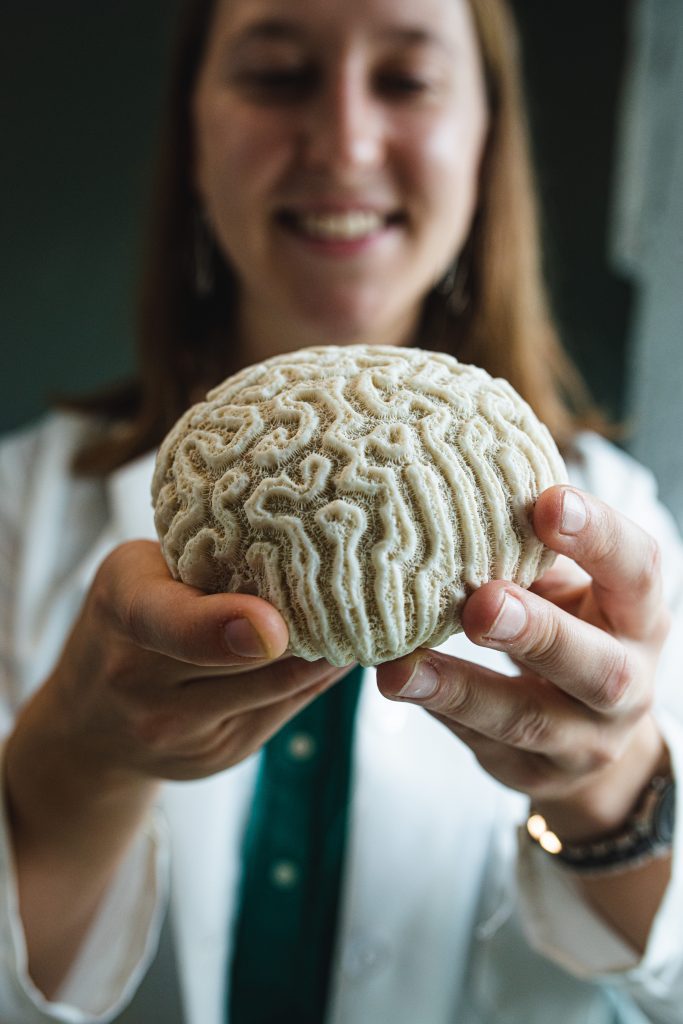

Grooved-brain coral is one of 30 hard coral species affected by stony coral tissue loss disease, which attacks the tissue of the living coral polyps that build skeletons like the one you see here. (Daniel Hentz, © Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

Oceanus: You're starting your career at a time when more than 50% of the world's coral reefs are in critical decline from a warming, more acidic ocean, and from diseases like the one you're studying now. How do you stay optimistic?

Becker: If I'm going to be doing this for the rest of my life, I want to know that there's hope out there. And so, I think it's really important to stay aware of the reefs that are still doing well.

I think of when I went to the Florida Keys with OceanX in 2019 to study stony coral tissue loss disease, which at the time was quickly spreading throughout Florida's coral reef. One day fairly early on in the cruise, we all dove at a place somewhat ironically named Wonderland Reef. There were corals there that were probably hundreds of years old, and more than a meter or two wide, with so much active disease on them. All of us came up from that dive feeling depressed, at a time when we felt like we were just scratching the surface of the disease. Then again, not far away, we dove at some smaller reefs and there were some cases where we saw corals that had clearly been sick in the past, but where the entire coral didn't die. In fact, you could see where the coral tissue was starting to regrow over the top of its former skeleton. That resilience gave me hope that we could help nature heal if we met it half way.

Oceanus: How do you expect your research will improve coral reef assessments in the future?

Becker: We've so far identified 25 microbes associated with stony coral tissue loss disease. Eventually, I want to be able to take a cup of seawater, see what combination of bacteria are in it, and be able to tell you what's a healthy reef and what's a reef that we need to target for restoration.

Cynthia Becker takes a water sample over a diseased coral near St. Thomas in the U.S. Virgin Islands in 2020. (Photo courtesy of Amy Apprill, © Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)