Amidst pandemic, researchers deploy new monitoring station in tropical Pacific

Stratus Ocean Reference Station to improve understanding of air-sea interactions

Estimated reading time: 3 minutes

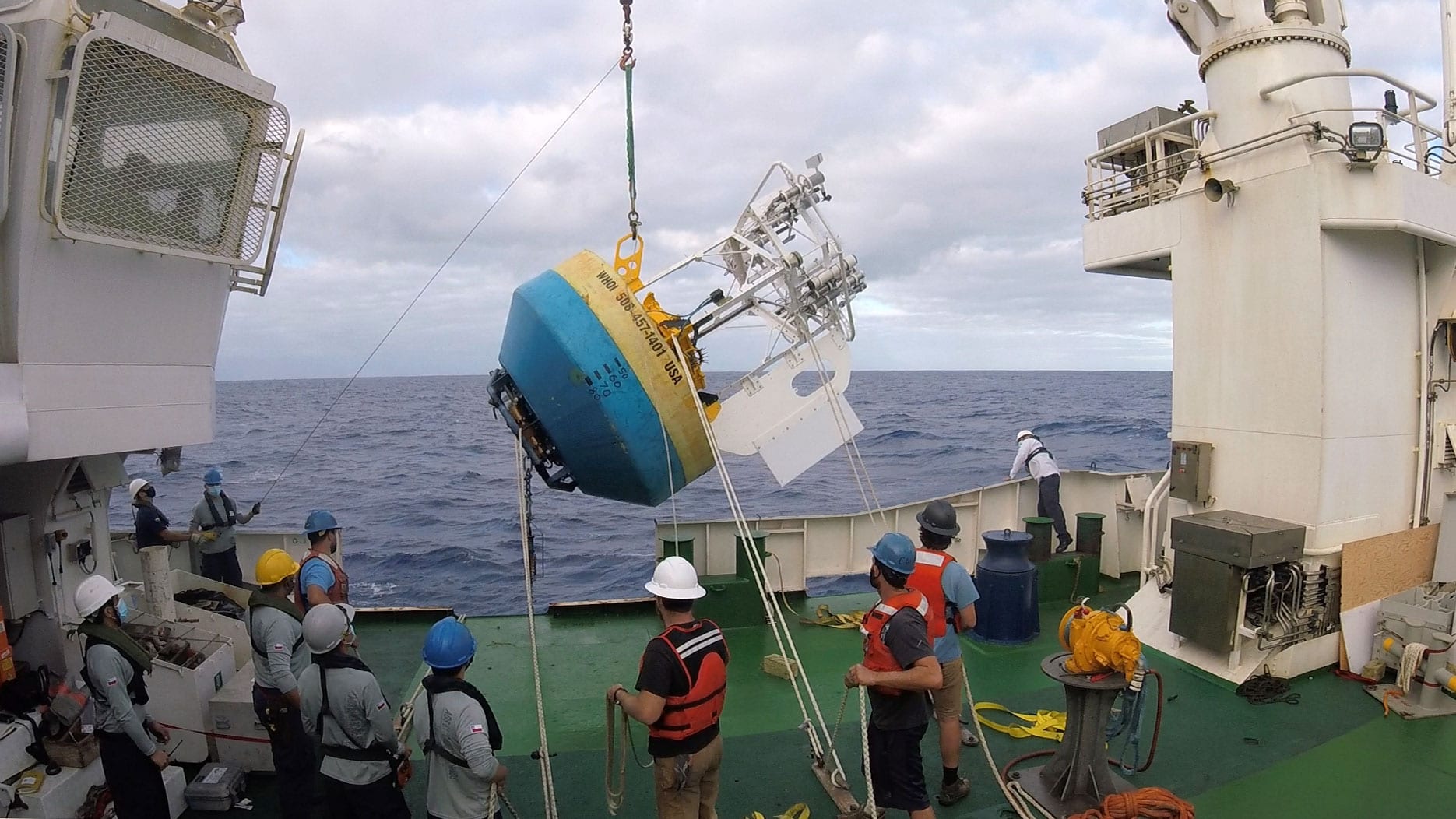

The third time was the charm for WHOI researchers and their Chilean partners to replace an instrument-rich surface mooring in the eastern tropical Pacific, 976 nautical miles east of Valparaiso.

Two earlier attempts to deploy a new Stratus Ocean Reference Station to collect atmospheric and oceanographic data had been scrubbed. First, because of the coronavirus and then because of the ship's late unavailability. Each time, the buoy had been shipped to Chile and then sent back to Woods Hole.

So when the new buoy was finally lowered into the ocean over the side of the Chilean Navy ship Cabo de Hornos on January 28, researchers' frustrations turned into relief and a sense of mission accomplished.

The Stratus 19 deployment continues a more than 20-year ongoing presence of a buoy in the otherwise data sparse area. It also continues a cooperative relationship with the Chilean Navy and Chilean scientists.

The buoy's instrumentation provides data on surface meteorology; air-sea fluxes of heat; upper ocean temperature, salinity, and velocity variability; and other measurements at basically one-minute intervals. Researchers use the data to calibrate climate models which otherwise can include inaccurate sea surface temperature measurements for the region. Since 2000, WHOI's Upper Ocean Processes Group has maintained the buoy in that region where stratus clouds make remote sensing difficult. It's one of three ORS that WHOI maintains.

The first attempt to install Stratus 19 was in March 2020. The buoy and instrumentation were sent to Chile and reassembled, the boat was about to be loaded, and the crew, including WHOI researchers, were about to embark on a two-week mission. At first the crew thought they could try to pull off the mission, despite reports of the coronavirus.

"What we do is inherently dangerous: going on a boat 1000 miles off the coast, using heavy machinery, and deploying a huge buoy. The idea of calling off the mission because of an influenza-like bug initially seemed a little overcautious," said WHOI's Emerson Hasbrouck, chief engineer for all three deployment efforts and chief scientist for the January deployment. "However, while we were onshore preparing to set sail, things globally started snowballing" about the pandemic.

The mission was postponed.

"There were too many things saying this cruise was fraught with peril," said Robert Weller, senior scientist with WHOI's UOC Group. The Chilean Navy's contractual flexibility also was helpful. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, which supports the ORS mission, pays for WHOI's use of the Cabo de Hornos.

A deployment attempt in December, 2020 was postponed one day before the buoy was shipping back to Chile, because the boat was not available then.

Location of the Stratus 19 Ocean Reference Station in the eastern tropical Pacific, 976 nautical miles east of Valparaiso (Illustration by Tim Silva, © Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

When the Navy alerted WHOI about an opening for ship time in January, researchers already had their bags packed and were ready to go.

"We felt like, we've got to retrieve the old buoy before it breaks. We can't go much longer," said Weller. Stratus 18 was far past its expected 12-14-month lifespan.

“There were too many things saying this cruise was fraught with peril.”

—Robert Weller, WHOI senior scientist

Following COVID-19 protocols and rushing to depart, researchers reassembled the buoy onboard instead of onshore, steamed to the location, and carefully lowered the buoy and its instrumentation into the water. "You can't just roll up, put down the tailgate, and throw the buoy off the back as you drive away," said Hasbrouck. After testing the new buoy, they retrieved the old one, which they don't think lost too much data, and went back to shore.

"This work is important and it's difficult even when we are not in COVID times," said NOAA's OceanSITES program manager Jim Todd added. He said the partnerships with Chileans help to make it a success.