Building a Tsunami Warning Network

Preparing for the next big wave is only partly about science

Since the great Indonesian earthquake and tsunami of December 26, 2004, policy-makers and scientists around the globe have been embracing a rare moment of public attention on the oceans, accelerating plans to create a comprehensive tsunami-warning network and to make citizens better prepared for the next massive wave. Another potent earthquake along the same fault on March 28, 2005, has increased that sense of urgency.

The Bush Administration has proposed spending $37.5 million over two years to greatly expand the nation’s tsunami monitoring network by 2007; the U.S. Congress is offering a competing plan that would spend $35 million per year through 2012. Internationally, the Indian, Australian, and Japanese governments have proposed systems for the Indian Ocean, as well as the Germans, who also propose networks for the Mediterranean Sea and North Atlantic.

But in the rush to set up networks, some scientists are raising questions, seeking to prevent a noble idea from being an uncoordinated, feel-good gesture that is at best inefficient, and perhaps ineffective. The questions include:

- Will there be enough funds to build the network and to maintain it in the future?

- Will funds for the proposed networks be in addition to, or merely redirected from, other scarce funding for ocean science?

- Can network efforts be coordinated with international partners and other global scientific efforts to maximize their benefits and mitigate their costs?

- What is the use of getting warnings from the sea, if no infrastructure exists in developing countries to convey it adequately to people on shore?

Making big plans

The U.S. initiative, which will be led by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS), would deploy 32 new buoys equipped with instruments to detect the pressure of a tsunami wave in deep ocean water. (See Throwing DART Buoys into the Ocean.)

Seven buoys would be moored in the Caribbean Sea and western Atlantic Ocean, with 29 more spread around the Pacific Rim, including four that are already operating.

The system also would include 40 gauges for sea level and tides, upgrades to 20 ocean-bottom seismometers, and funding for communications systems, risk assessment, computer modeling and prediction, education programs, and emergency preparedness.

The program does not provide much, if any, funding for ocean scientists outside of NOAA or USGS.

Internationally, the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty Organization (CTBTO) is in the process of setting up 320 seismic monitoring stations around the world, and 175 are already working (including eight in Indonesia, Thailand, and Sri Lanka). But the system was designed for reconnaissance, not to disseminate emergency warnings. Scientists and tsunami monitors currently rely on the Global Seismic Network to detect the location and depth of earthquakes—a small fraction of which may spawn tsunamis. In March 2005, the organization began making plans to provide real time data from selected stations on a test basis to tsunami warning centers and national data centers.

The expanded tsunami network would be a key first piece in the Global Earth Observation System of Systems (GEOSS), a 60-nation program to coordinate studies of Earth systems that NOAA Administrator Conrad Lautenbacher has been promoting. Proposed several years ago, GEOSS has been stalled in hard budget times, but the tsunami network has provided motivation to get the program off the ground.

“The world’s attention has been focused on the vulnerability of people who live on the edge of the ocean, and we have a responsibility to respond to their need,” said John Marburger, science adviser to President George W. Bush, during a January news conference.

Budget crest or trough?

The proposed $37.5 million for the U.S. tsunami-monitoring program does not necessarily mean new money for ocean science. NOAA has requested $9.5 million for the tsunami program in the agency’s 2006 fiscal year (FY06), which begins Oct. 1, 2005; USGS requested $5.4 million.

But the current plan calls for the program to start in 2005 in order to be completed by the summer of 2007. To accomplish that, NOAA and USGS are requesting $22 million as part of an $80 billion emergency-spending bill submitted to Congress in February 2005 for military operations in Iraq and Afghanistan.

If the supplemental appropriation for tsunamis is not approved, however, NOAA would either have to have to take funding from other programs in the FY05 budget or push the start of the network back until 2006. Not incidentally, the NOAA research budget is scheduled to be cut by 6.7 percent in FY06; USGS will lose 4.6 percent.

Even if NOAA and USGS receive the $37.5 million, that will only put 20 of the 32 buoys in the ocean. Deploying the other 12 will require additional funding in 2007.

“If there is no ‘new’ money, they will have to take the funds for the hardware and ship time out of existing ocean funds,” said Robert Weller, WHOI senior scientist in Physical Oceanography Department and director of the NOAA-sponsored Cooperative Institute for Climate and Ocean Research. “This will, at a time of very tight funds, most likely severely damage one or more other programs.”

Built to last

The crucial issue, as ocean scientists see it, is sustaining the system once it is installed. Estimates range from $5 million to $12 million per year—or 10 times the $37.5 million startup costs—to maintain the buoy-and-seismometer network and for staffing the operations centers and research and education programs to make the network useful.

“The Administration’s proposed tsunami warning system would deploy many single-purpose buoys,” John Orcutt, deputy director of Scripps Institution of Oceanography and president of the American Geophysical Union, said in testimony to the Science Committee of the U.S. House of Representatives. “Major tsunami events occur at time scales from decades to centuries, and even in the Pacific, tsunamis don’t occur often. Between major tsunamis, the NOAA Pacific Tsunami Warning Center in Hawaii has a hard time maintaining its budget and personnel.”

“We can think of solutions to the tsunami problem, but we have to decide if they are worth the cost,” added Robert Detrick, a marine geologist and vice president for marine operations at WHOI. “Does society have the willpower to pay for these observations over decades or centuries? If we build a platform that allows other research to be conducted, we will give the system value even if a tsunami never occurs.”

For instance, tsunamis could be just one of several natural hazards and phenomena monitored by a more well-rounded observing system. Such a system would simultaneously address several societal needs and scientific concerns—El Niño, earthquakes, ocean circulation changes, chemistry, ocean life—so that even if there is not a tsunami for a hundred years, the observation program could collect other critical data.

“This event is another indication of the pressing need for ocean observations on a global scale,” said Weller. “We should be moving toward a long-term, ocean-observing strategy. We should take this opportunity and accelerate a multi-agency, multipurpose program to get global real-time ocean observations for diverse societal benefit.”

The Ocean Observatories Initiative led by the National Science Foundation includes an array of deep-ocean buoys that serve a variety of research endeavors—including bottom pressure gauges and seafloor seismic instruments—with instruments strung from the sea surface to the ocean floor. That program also includes cabled seafloor observatories, robotic vehicles, and drifting observatories.

David Green, leader of planning and integration for the NOAA program, said the agency has been told to design a tsunami-specific network, and while it is “planning for expanded capability—a platform for future sensors—we are not building that in right now.”

Waves of information

“Is a tsunami network a real help for society?” Weller asked. “You can have warning buoys, but if there is not the shore-side infrastructure, training, and education to make use of the warnings, what good has been accomplished?”

WHOI Senior Scientist Alan Chave recalls growing up in Honolulu, where there are sirens and regular tsunami drills to keep the population prepared for the inevitable. “How do we get the word out to the people whose lives we want to save?” Chave said. “It could be difficult in countries with so little infrastructure. We need to be clever.”

In a January hearing before the Science Committee of the U.S. House of Representatives, Chairman Sherwood Boehlert, a Republican from New York, criticized the Bush Administration’s $1.5 million proposal for tsunami education and outreach, calling it “tip money in this town.”

“We need an education and awareness campaign, including emergency planning, drills, and training,” said Laura Kong, director of the International Tsunami Information Center. “The challenge in the South Pacific, for instance, is that there are many small islands and poor countries with very little infrastructure.” (See MIT/WHOI Graduate Leads the World’s Tsunami Awareness Program.)

News Analysis by Mike Carlowicz

Slideshow

Slideshow

Satellite images reveal the shore of Banda Aceh, Indonesia, on June 23, 2004. (Credit DigitalGlobe)

Satellite images reveal the shore of Banda Aceh, Indonesia, on June 23, 2004. (Credit DigitalGlobe)- This December 28, 2004 image of Banda Aceh shows the total devastation from the tsunami wave. (Credit DigitalGlobe)

- Gleebruk Village in Indonesia is lush with vegetation and teeming with human activitiy on April 12, 2004. (Credit DigitalGlobe)

- By January 2, 2005, the landscape of Gleebruk Village has been scoured by the violent tsunami surge. (Credit DigitalGlobe)

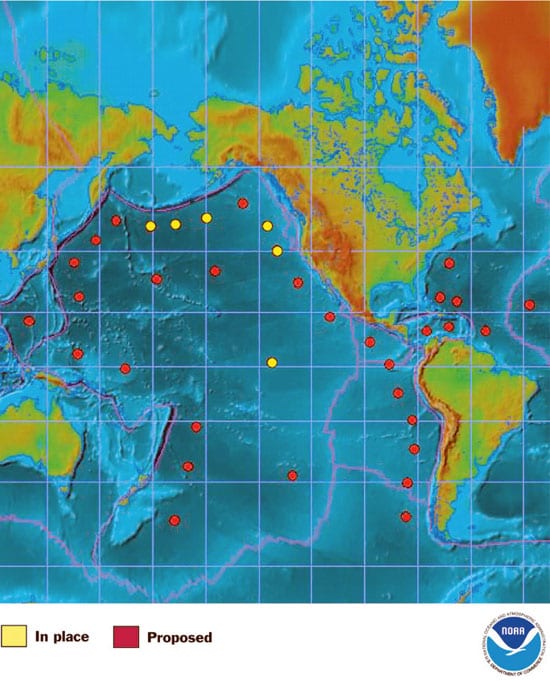

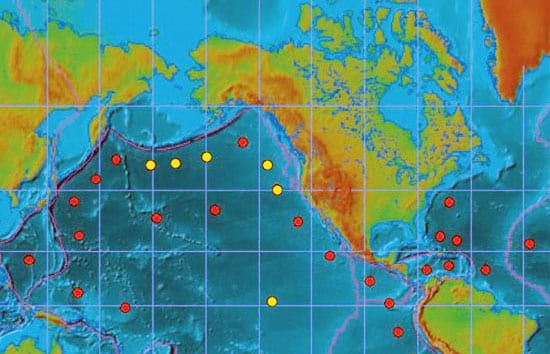

- A global network of seismic monitoring instruments—including 141 existing and 8 planned stations—allows researchers to detect and locate undersea earthquakes. It does not, however, confirm the presence of a tsunami wave—only the possibility of one. (Credit NOAA)

- The tsunami monitoring network proposed by the Bush Administration will include 36 buoys in the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans, four of which are already operating. (Credit NOAA)

Related Articles

- Can seismic data mules protect us from the next big one?

- A New Tsunami-Warning System

- Lessons from the 2011 Japan Quake

- How to Survive a Tsunami

- Morss Colloquia Focus on Science and Society

- Lessons from the 2004 Indian Ocean Tsunami

- A ‘Book’ of Ancient Sumatran Tsunamis

- MIT/WHOI Graduate Leads the World’s Tsunami Awareness Program

- Throwing DART Buoys into the Ocean

Featured Researchers

See Also

- USGS: March 28 Indonesian Earthquake Information

- U.S. House of Representatives - Tsunami Legislation

- U.S. Senate: The Tsunami Preparedness Act of 2005 - Full Committee Hearing

- NOAA Tsunami Resources

- Tsunami Slide Sets

- NOAA Indonesia Tsunami Animations

- Tsunami Information from WHOI's Coastal Ocean Institute