Are we heading toward another Little Ice Age?

WHOI climate scientists sound off on the likelihood of 'global cooling'

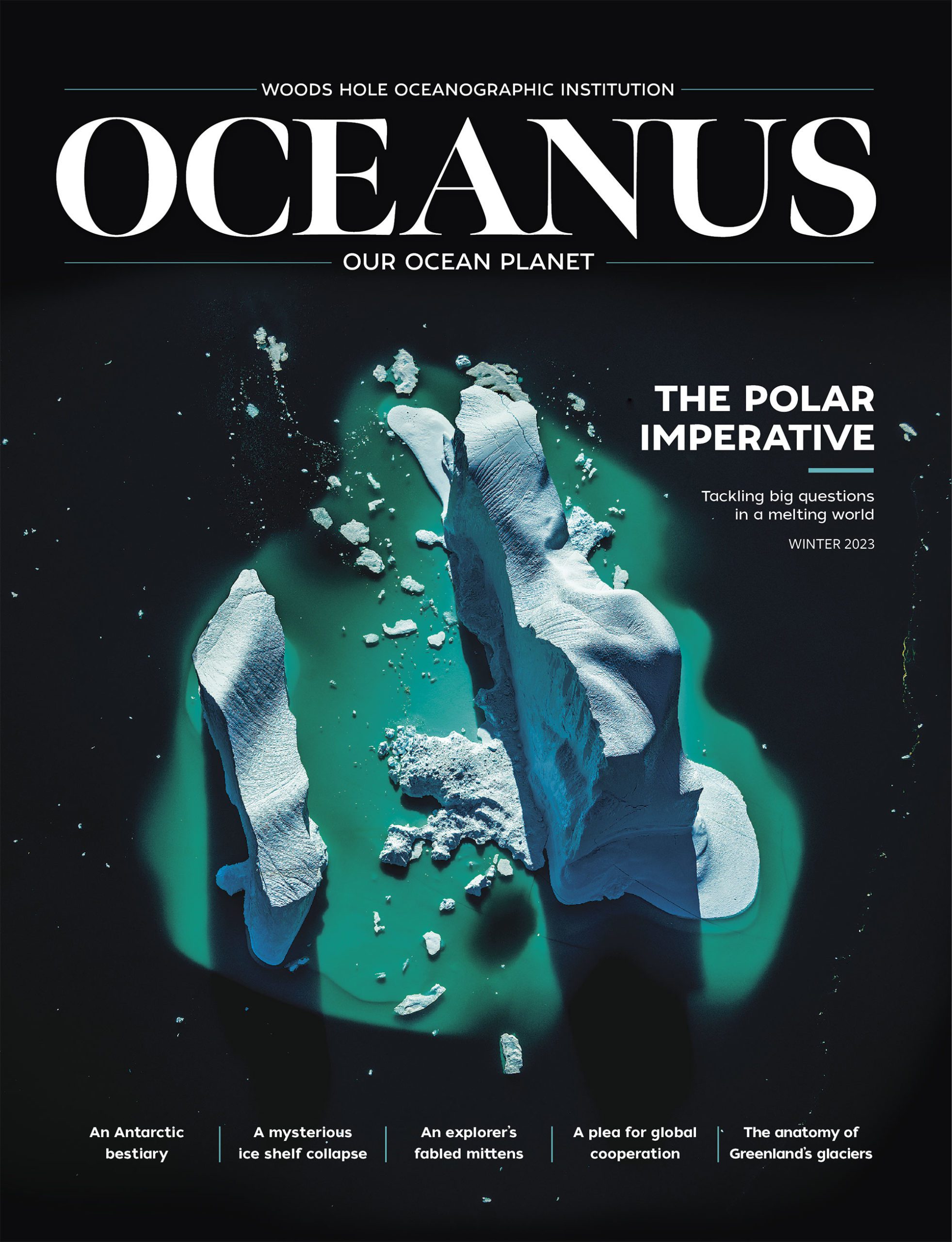

This article printed in Oceanus Winter 2023

This article printed in Oceanus Winter 2023

Estimated reading time: 4 minutes

In the 2004 blockbuster “The Day After Tomorrow,” the Northern Hemisphere experiences an abrupt and catastrophic plunge into Ice Age conditions. The culprit? Extreme rates of melting ice from the poles cause a massive disruption in the ocean currents that distribute heat around the planet. In the movie, North Atlantic currents responsible for the temperate climate along the North American East Coast and Western Europe suddenly grind to a halt, causing the northern United States and the United Kingdom to freeze over and unleashing terrible storms around the world.

It might seem completely off-base to imagine that the heat-trapping gases emitted by humans could cause “global freezing” rather than “global warming.” But in fact, scientists have long hypothesized that greenhouse gases could cause cooling in some places and warming in others due to changes in ocean circulation. There is genuine concern and no shortage of studies looking into whether the unprecedented melting of the Greenland Ice Sheet is impacting the North Atlantic subpolar gyre and Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC), important drivers of the ocean’s circulation system and Earth’s climate.

So, could we one day see the abrupt climate change depicted in “The Day After Tomorrow”? Or can we expect a more gradual transition to a “mini Ice Age” as some have speculated?

Probably not, says WHOI physical oceanographer Jake Gebbie.

To look into our climate future, we need to review the past. An Ice Age is a “glacial period” in which the Earth’s surface and atmosphere cools by over 5°C, causing the polar ice caps and glaciers to expand. Brought on by naturally-occurring shifts in the Earth’s orbit and tilt, which change where solar energy hits Earth’s surface, these periods occur fairly regularly and can last tens of thousands of years.

A shorter period of cooling, such as the “Little Ice Age” between the 14th and mid-19th centuries, saw temperatures that were half a degree Celsius (about 1°F) cooler in Europe than today’s average temperatures. During the Little Ice Age, volcanic activity blocked solar radiation from reaching the Earth, which, combined with naturally reduced solar activity, the build-up of solar-reflecting ice (the albedo effect), and other potential factors, all conspired to cool the northern hemisphere.

“What caused the Little Ice Age to last for centuries in the Northern Hemisphere is a matter of debate,” Gebbie says. “The ocean had a role, but the driver likely had more to do with volcanoes and solar activity. There is less evidence that it was driven by ocean circulation.”

So, let’s say that, in the next few years, a spate of volcanoes erupt and sunspots reduce solar radiation as much as they did during the Little Ice Age. With today’s record-breaking heat waves, would those natural phenomena be enough to cool the planet to pre-industrial temperatures–or even trigger a Little Ice Age? Not likely, says Gebbie, because there’s now so much heat baked into the Earth’s system that the melting ice sheets would not readily regrow to their previous size, even if the atmosphere cools.

“So far, there may be a balance in the North Atlantic between the energy from atmospheric CO2 ramping up and the countereffects of ocean circulation,” Gebbie says. “But the CO2 is accelerating so much. For that reason, the community consensus is that possibility of the North Atlantic significantly cooling in the near future is very low.”

How do scientists know about the past climate? In some cases, the climate record is preserved in ice cores. In a 2021 research study, WHOI glaciologist Sarah Das and colleagues investigated a 140-meter long cylinder of ice from a mountain range in coastal Greenland. They found that periods of rapid warming over the past 2,000 years actually caused more snow to fall in west Greenland, causing some coastal glaciers to expand.

WHOI glaciologist Sarah Das conducting fieldwork in Greenland (Photo by Chris Linder, © Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

“Now we’re past the tipping point. The rapid warming of the past century is accelerating glacier melting so much that the ice caps are shrinking rather than growing,” says Das. “These coastal records are a clue to just how much we’ve already switched the state of the climate system.”

The trajectory of Earth’s orbit is very slowly shifting the Northern Hemisphere away from the summer sun, Gebbie says, so that could help preserve some Arctic ice. But despite this trend–and geological evidence of minor planetary cooling over the last four thousand years–the signs don’t point to an actual glacial period.

“Those changes are very slight, much smaller than what we’ve seen over the last five decades,” Gebbie points out. Based on the growth of ancient marine creatures buried in ocean sediment, Gebbie says these changes likely reflect fluctuations in summertime temperatures rather than Earth’s average temperature.

For those who look to the possibility of an impending Little Ice Age to counterbalance the impacts of human-induced climate change, the scientists say, be careful what you wish for.

“The ocean is acting to slow down global warming now. But even after we figure out a way to decarbonize our economy, the ocean will continue the warming trend because the heat is already in the pipeline,” Gebbie says. “All the evidence we have so far is that the rate we’re changing the planet is greater than what the Earth can account for. It moderates on time scales way beyond our lifetimes.”