Action, Camera … Lights

New deep-sea “light post” illuminates the ocean's perpetual night

Exploring the seafloor can be like using a flashlight to find something in a dark basement. Just one-third of a mile beneath the sea surface, ambient light fades to black, requiring oceanographers to beam their own light to see what’s around them, as well as to take photos and video of the deep.

Until now, illumination has come mainly from multiple lights mounted on deep-sea vehicles. In summer 2005, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution scientists and engineers designed something entirely different: a tall, portable light system. Named the “deep-sea light post,” it blazes with a single, 1,200-watt bulb on top of an 8-foot pole, powered by five 100-pound batteries in watertight housings.

The light post’s light is about 20 times more powerful than the average 60-watt household bulb. It gives off nearly as much light as one of the bulbs used to illuminate Boston’s Fenway Park.

Best of all, the 1,400-pound instrument—which weighs 200 pounds in water—can be moved around the seafloor by the remotely operated vehicle Jason 2. This provides oceanographers with views of large seafloor features from different angles, essentially transforming areas of the deep sea into a photography studio.

Getting the big picture

As high-resolution photography and video have become more affordable and routine in deep-sea research in the last decade, so has the need for powerful and adaptable lighting systems. WHOI geologist Dan Fornari spearheaded the project to build the light post in just six weeks with several WHOI researchers and engineers, including Marshall Swartz and Steve Liberatore.

It was first tested in September 2005 for use with a new University of Washington high-definition video camera mounted on Jason 2that provided live broadcasts from the seafloor to the Internet. WHOI engineer Robert Fuhrmann, a member of the Jason 2 team, assisted with operations.

“SPECTACULAR,” oceanographer Debbie Kelley of the University of Washington wrote of the light post in an e-mail after testing the instrument on the Juan de Fuca Ridge offshore Seattle. There, the rugged and strangely beautiful seafloor landscape is carpeted with crabs, snails, and tubeworms living around tall hydrothermal vent chimneys, some the size of six-story buildings.

“The camera worked, the light turned on, and it was as if we had walked into the Land of the Hobbit,” Kelley wrote from the research vessel Thomas G. Thompson. “It gave us views of the field we have never seen before. It was something I will not forget for a long time.”

The light post’s broad, bright beam gave Kelley and John Delaney, both lead scientists on the expedition, a chance to see a large portion of the 25-meter (82-foot) hydrothermal chimney called Hulk.

“For the first time, I got a big overview of the structure,” Kelley said. “Normally I’m just getting little glimpses.”

Adding improvements

With light post’s success on the expedition, Fornari has written a proposal to the National Science Foundation to start improvements. Currently, the light post had to be switched off and on using Jason 2, which can be time-consuming. Fornari proposes to add acoustic controls to trigger the power switch and to command pan-and-tilt functions to move the light head. He also plans to double the light post’s power; batteries now provide 70 minutes of light operation while on the seafloor.

Powerful lights, adapted for use in the cold temperatures and crushing pressure of the deep ocean, have been developed by the San Diego-based company DeepSea Power & Light and used on diving vehicles at WHOI since the early 1990s. Hollywood directors have even capitalized on this type of intense lighting, perhaps most famously in filming underwater scenes in the 1997 movie Titanic.

“Light is key for getting excellent images of the seafloor,” Fornari said. He envisions having at least two light posts to meet researchers’ needs and to gather photographs and film to help people learn about deep-sea research.

With lights external to Jason 2, for example, scientists will be able to photograph the vehicle working on the seafloor and give people a better idea of exactly how scientists do research in the deep.

“We want to show our vehicles working on the seafloor,” he said “in the same way that NASA provides images of the Shuttle working in space.”

Funding to develop the deep-sea light post came from Multidisciplinary Instrumentation in Support of Oceanography, a community instrumentation facility for deep-sea digital imaging at WHOI funded by the Ocean Sciences Division at the National Science Foundation.

Slideshow

Slideshow

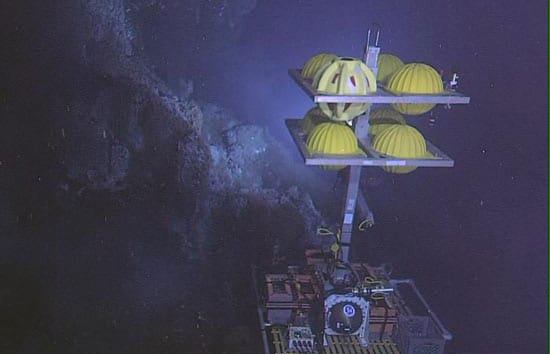

- The deep-sea light post, on deck this September on the research vessel Thomas G. Thompson, uses a single, 1,200-watt bulb (shown here under the lower left yellow flotation ball). It is powered by five 100-pound batteries in watertight housings, which are secured at the instrument's base. The yellow balls at top provide buoyancy and stability.

- In a painting of a hydrothermal chimney named Hulk on the Juan de Fuca Ridge, a camera mounted on the remotely operated vehicle Jason 2 captures high-resolution images using light from the deep-sea light post. The light post?s light is about 20 times more powerful than the average 60-watt household bulb. (Illustration by E. Paul Oberlander, WHOI) (Illustration by E. Paul Oberlander, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

Video

Related Articles

- How WHOI helped win World War II

- Learning to see through cloudy waters

- Are warming Alaskan Arctic waters a new toxic algal hotspot?

- 5 essential ocean-climate technologies

- A curious robot is poised to rapidly expand reef research

- A new way of “seeing” offshore wind power cables

- New Techniques Open Window into Anatomy of Mollusks

- The Deep-See Peers into the Depths

- Re-envisioning Underwater Imaging