A ‘WHOI Way’ of Doing Things

A conversation with research associate George Tupper

People who have worked at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution know it in their bones. People who work with WHOI feel it, too: There’s a WHOI culture, a WHOI way of doing things. It spawns innovation and produces high-quality results, but it’s not easy to put into words.

George Tupper went a long way toward describing it in an interview for the WHOI Oral History Project. Raised in Minnesota, Tupper never saw the ocean until he was 19. After high school, unable to afford a college education, he enlisted in the U.S. Air Force, where he worked on maintaining radar and missile systems for eight years. “I got discharged in 1967 on a Friday and started working here [at WHOI] on Monday.”

Originally hired by the WHOI Buoy Group as a current-meter technician, he soon began designing moorings and leading Buoy Group cruises, averaging two to three months per year at sea for the rest of his career at WHOI. He “retired” in 2001 but has continued to work as a WHOI casual employee. Since his retirement, he has taken part in roughly 40 research cruises, mostly recently in March, 2010, to Saudi Arabia to analyze water samples from the Red Sea for salt and oxygen content. Something about the WHOI culture keeps bringing people back.

Why did you pursue a career in oceanography after leaving the Air Force?

Well, uh, in all fairness, I was just looking for any job in the electronics field. I can’t hang my hat on getting interested in oceanography. I came to this place as one of many that might employ me.

You came to WHOI from a place where if they asked a new lieutenant, “How would you perform this particular function?” and the correct answer would be, “I’d get six enlisted men and instruct them what to do.”

Yep. Question: “How do you put up that flagpole?” Answer: “Men, put up that flagpole!”

All I had for reference was the military, which was quite hierarchical. I came here, and the first cruise I went, other than being horribly seasick, I was so amazed that the grunts like me, and my co-workers, and the Ph.D.’s were all sweating bullets doing manual labor, working on getting this mooring over the side. The chief scientist was working as well. That was quite an education for me to see everybody pitching in together. Nobody was saying, “That’s not my job. Hey, you go do that.” I’ll never forget it.

There’s not a whole lot of intellectual snobbery going on here. When you have an idea, people don’t necessarily look at you to see how many degrees you have. They listen to ideas, and if it has merit, off you go, and if it doesn’t have merit, it gets quashed, and nobody’s feelings are hurt.

So you went from a situation in which you had to answer to higher authorities, who may not know as much about a subject as you do, to a place where everybody’s on the same boat?

When I first came here, it amazed me how things got done [snapping fingers]—just like that. Things happened quickly, without a whole bunch of authorizations.

One of the glaring differences between the military and when I came here was I was free to innovate. That was like a breath of fresh air. Not that the military was bad, but there was a whole different concept at WHOI of working with an instrument—an instrument, say, designed by some guy who didn’t know a whole lot about where it was going, and how it worked, and what effects the physical environment in which it was used would have.

You put those instruments out to sea for a while, and you start learning things about them. You can see things that you would design differently. And I was given the opportunity to do that.

And the other thing was an enormous feeling that I was trusted. No one was watching my back and saying, “Did you do this? Are you sure you worked eight hours on that?” I’m a grownup, and I was treated like one from the time I got here. It’s a wonderful thing, and it makes you more responsible than if there’s someone looking at you with time charts and stopwatches.

You knew you were never going to become a millionaire working at WHOI.

After I had been here a few months, I got a job offer from someplace else for more money. I said, “No, I’m having too much fun here, thank you.”

What did you think about your co-workers at WHOI?

I was blown away by most of them. It was just a pleasure to be surrounded by people like that, and I learned by working with them. I was kind of argumentative in the Air Force. If I got my mind set a certain way, nobody could change it. The best thing I learned here was to question myself.

My co-workers would challenge me with reasonable arguments, and I began to think, “Wait a minute. Am I trying to prove myself right, or am I trying to learn something?” That’s a real breakthrough: to be totally objective and to be able to say, “I was wrong and I can change my mind.” That’s what working with these guys did for me. You can’t help but respect them. Your sexism goes away, too, because half of them are women.

One aspect of WHOI that strikes me is that if you want world-class science, you obviously need world-class scientists. But you also need world-class technicians, who can deal with, for example, how to deploy 3,000 meters of cable at sea and bring it back safely.

Yeah, and I think that’s in line with the intellectual snobbery that this place doesn’t have. The scientists we work for, who generate the money to do our experiments, have had the wisdom to really be able to delegate the mechanical details. They trust the technical folks that they hire and pay to do the work. It benefits them, and it benefits us.

On research cruises, you’ve got three distinct groups: the ship’s personnel, the technical personnel, and the scientists. How do these groups segregate themselves?

No, no, not on WHOI ships. My perception is, on WHOI ships, there’s little if any segregation. The crews respect the scientists, and the scientists respect the crews, because each one can’t do anything without the other. I think that’s kind of a unique WHOI thing. I’ve been on other ships where it’s not done as well, and all is not wonderful and ginger peachy.

If someone isn’t doing things, for lack of a better term, “the WHOI way,” what do you do?

Hmm, that’s a good question. Whew, because it has happened. Well, you know, it depends on how much “unWHOI-like” they are. If they’re a danger to themselves, or other people, they’ll get talked to by one of us, and if that doesn’t work, by the captain, surely.

Did you have any interest in the science that was being done with your instruments, or was your interest developing the best instrument you could?

I would love to be able to say that I really, truly had an interest in the science. I did, in the sense that I know it’s valuable. And you cannot help but absorb some of the knowledge of the guys that you work for.

I don’t know how this came through to me, but I can remember that ever since I’ve been here, I knew that data is almost sacred. The scientists have a job to do and questions they want to answer. If your methodology allows them to answer those questions, you’ve done your job. With most of the guys that I’ve worked with, there’s a sense of “If I gloss over something, or if I skip this detail, or if I don’t doublecheck that solder joint, or make sure the data tape is in there straight, there goes the scientist’s data record, and for no particular reason other than I was lazy.” And that’s just something that we’d rather work all night to get it right, rather than take a chance on losing what could be invaluable data.

Why don’t you stay retired?

I realized slowly that I really, really like this place. And I really didn’t want to just cut the switch and go away and never come back. I have been here so long that there are things that I know how to get done much quicker than someone else who would have to learn: “Who do I talk to for this? Where do I go for that? Who does this? Who does that?” I know that stuff. I’ve got so much corporate memory. Until I croak, why not utilize it?

—Interview by Frank Taylor. Edited by Cherie Winner and Lonny Lippsett

Slideshow

Slideshow

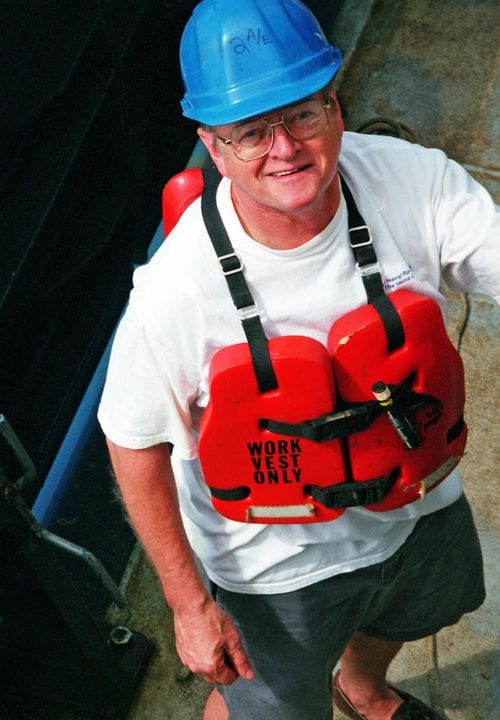

- George Tupper came to work at WHOI in 1967 after an eight-year career in the U.S. Air Force and experienced a culture shift in how work was done. (Terry Joyce, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

- Since George Tupper "retired" in 2001, he remained a casual employee of WHOI and has participated in some 40 research cruises. (Terry Joyce, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

- Over his nearly 40-year career at WHOI, research associate George Tupper has developed, maintained, and operated many different types of oceanographic instruments, inclucing the CTD, which stands for "conductivity-temperature-depth." It measures seawater temperature and salinity through the water column. (Tom Kleindinst, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

- A fogbow—an Arctic meteorological phenomenon—hovers over George Tupper aboard the Swedish icebreaker Oden. Tupper took part in a research cruise in 2007 to search for hydrothermal activity beneath the polar ice cap. (Chris Linder, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

- George Tupper (center) was a workhorse during round-the-clock CTD operations aboard the 2007 expedition to the Gakkel Ridge in the Arctic Ocean. (Chris Linder, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

Related Articles

Topics

Featured Researchers

See Also

- A Mooring Built to Survive the Irminger Sea An article by George Tupper in Oceanus magazine

- WHOI Mooring Operatioins, Engineering & Field Support Group

- Sub-Surface WHOI Mooring Operations Group