Climate & Weather

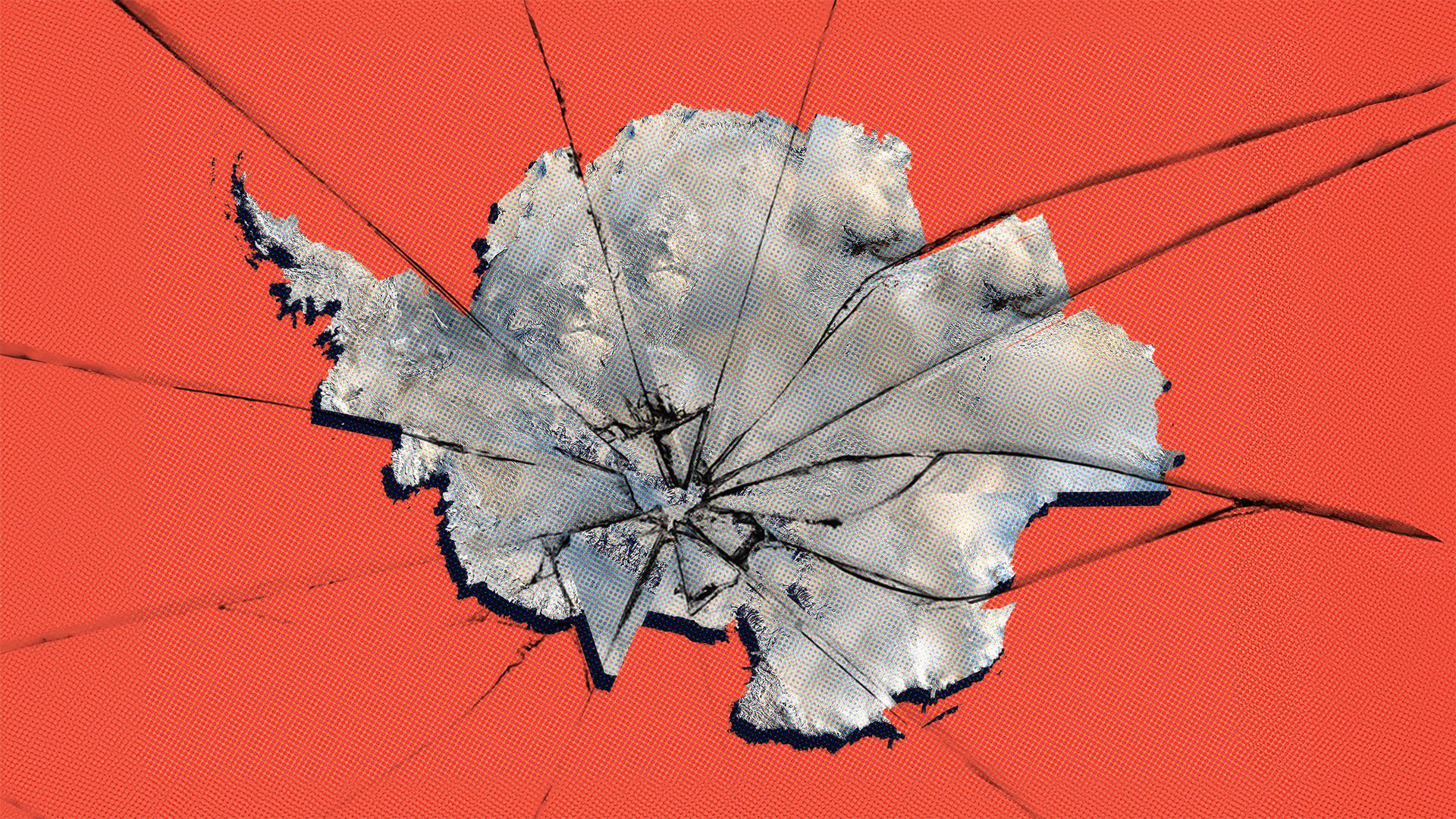

A cold case, filed

In March 2022, the world was abuzz with news of the Conger ice shelf’s collapse in East Antarctica. The shelf, measuring 460 square miles—an area larger than New York City—was a region as obscure to the public as it was remote. And for good reason: an ice shelf had never before collapsed in East Antarctica. So, how did this one?

It took two weeks for the ice shelf to blow apart, in an area widely considered by scientists to be relatively stable amid the changes wrought by global climate change. Stable because East Antarctica sits above sea level in generally cooler air temperatures, unlike West Antarctica and the Antarctic Peninsula, where warming Atlantic waters regularly lap up against a literal watch list of vulnerable ice shelves. Most scientists had little reason to suspect the Conger shelf would collapse, given its location. Catherine Walker, a glaciologist at WHOI, wasn’t most scientists.

Three months before Conger’s collapse, Walker had been scanning satellite images of a nearby ice shelf in East Antarctica when she noticed something weird happening to Conger.

“Looking at a big satellite picture of the ice shelf, [the surface] just looked like some bumps, but when you zoomed in, there were cracks probably hundreds of meters long,” says Walker. “By the time we started watching Conger before it broke up, these fractures were probably 16-20 kilometers (10-12 miles) long.”

Now, after a year of data analysis and investigation, Walker suspects the fissures that led to the collapse were caused by a perfect storm of conditions.

Her forensic tools, which include five types of satellite imagery ranging from standard high-resolution cameras to thermal imagery, provided an x-ray view of fractures both above and even below the ice shelf.

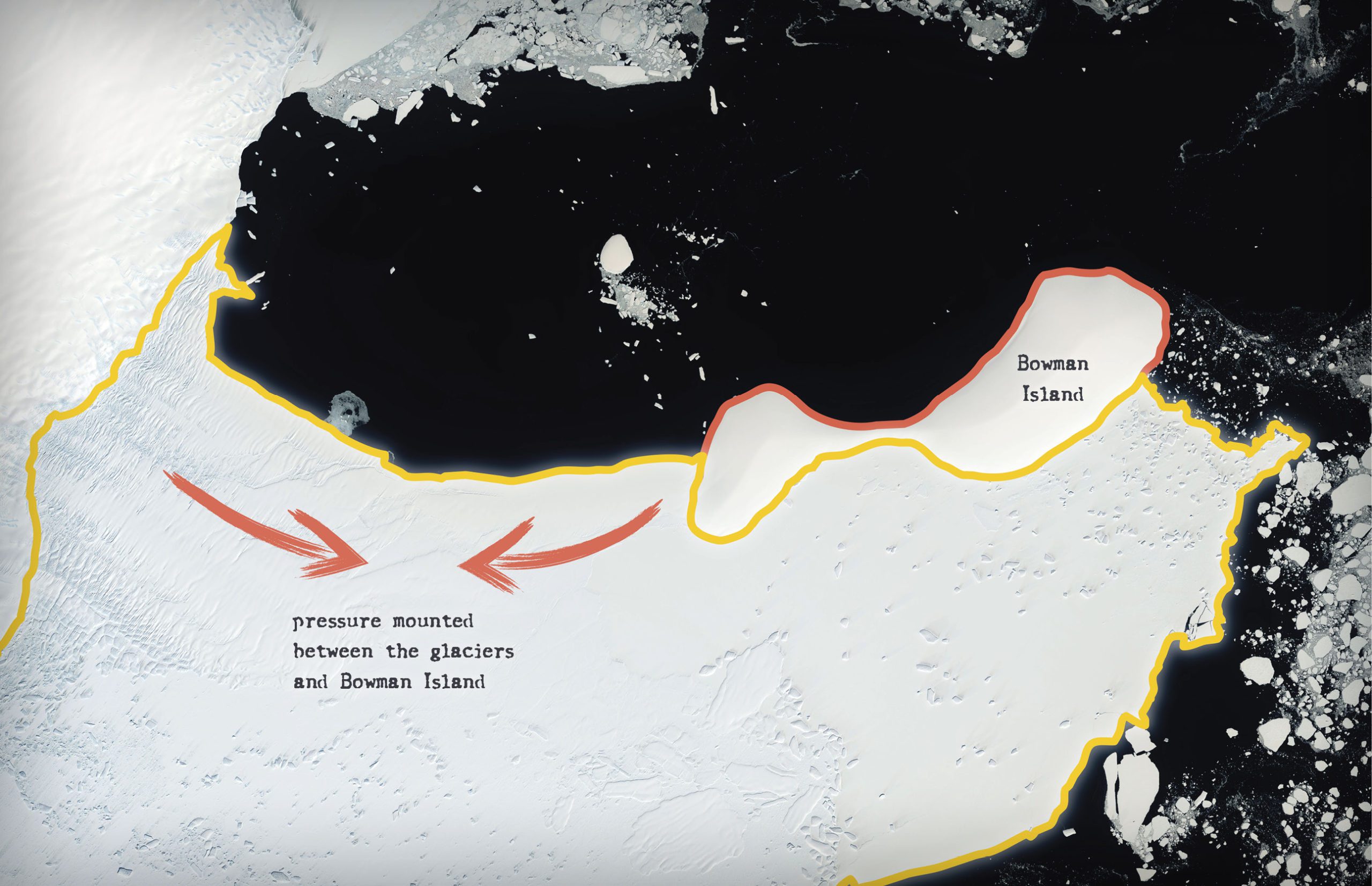

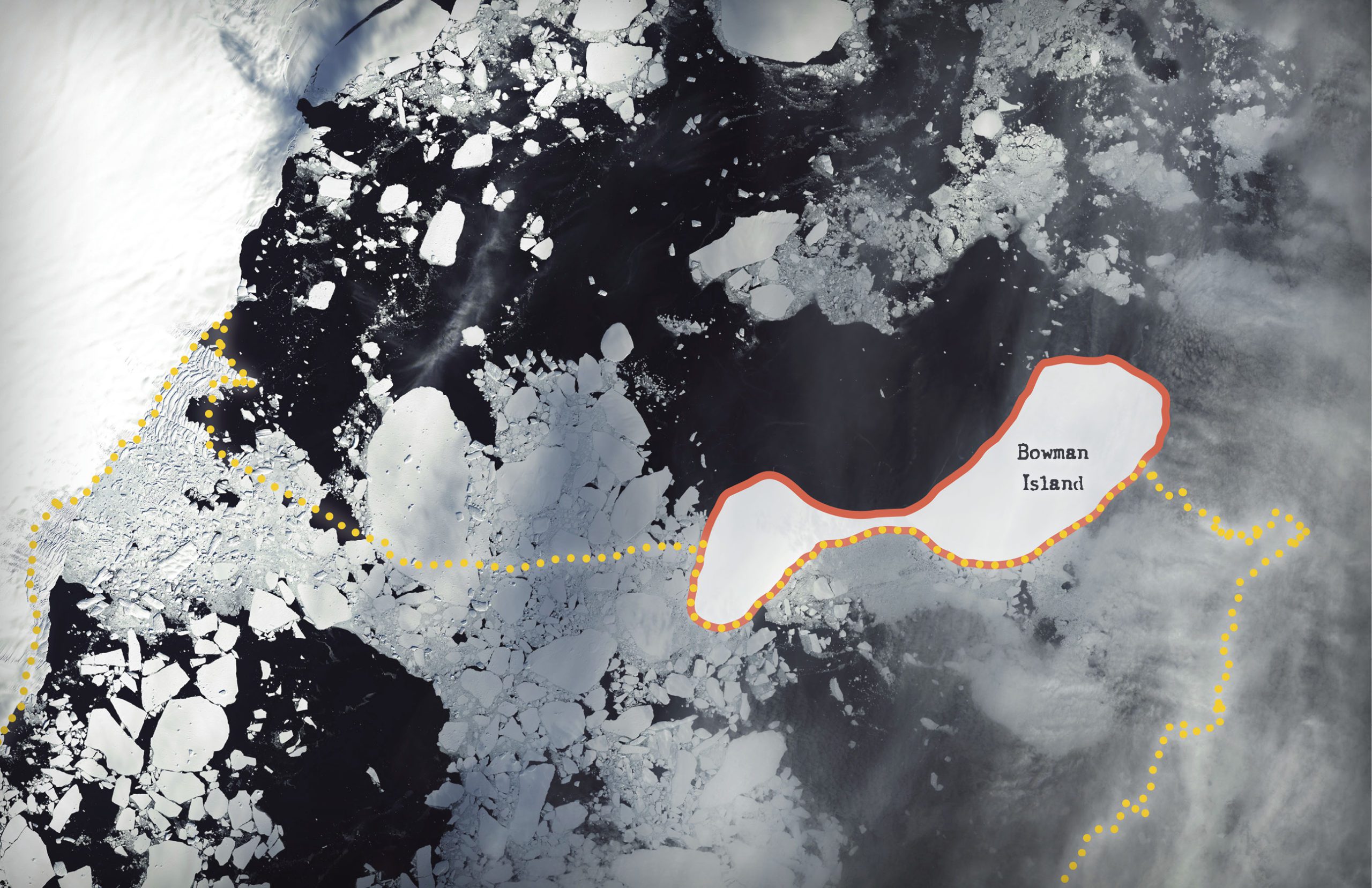

The first signs of stress appeared in 2020 when crescent-shaped cuts showed up along the ice shelf’s exterior along with a growing spider web of cracks. Both were clues of mounting pressure, which had likely originated behind the ice shelf. There, warming global temperatures had caused the melting of glaciers inside the continent’s interior, which began pressing forward toward the coast. In the ocean in front of Conger, was Bowman Island, a landmass connected to the shelf through a bridge of ice. As Conger was thrust forward by the glaciers behind it, Bowman stood in the way. The ice shelf had nowhere to go.

“Bowman Island essentially became a slow-moving rock hitting a windshield,” says Walker.

In 2022, an anomalously warm rain poured over the ice sheet, deepening its cracks and melting the already thin structures that held Conger together.

The ice sheet’s collapse has since put the whole region’s stability into question. East Antarctica, which comprises more than two-thirds of the continent, could have more devastating impacts on sea-level rise than West Antarctica if its ice shelves continue to falter. For Walker, Conger made it impossible to ignore the East Antarctic’s vulnerability.

“It shows how much we still don’t know,” says Walker. “Once you get rid of ice shelves like this one, that’s when you see Antarctica really start to change.”