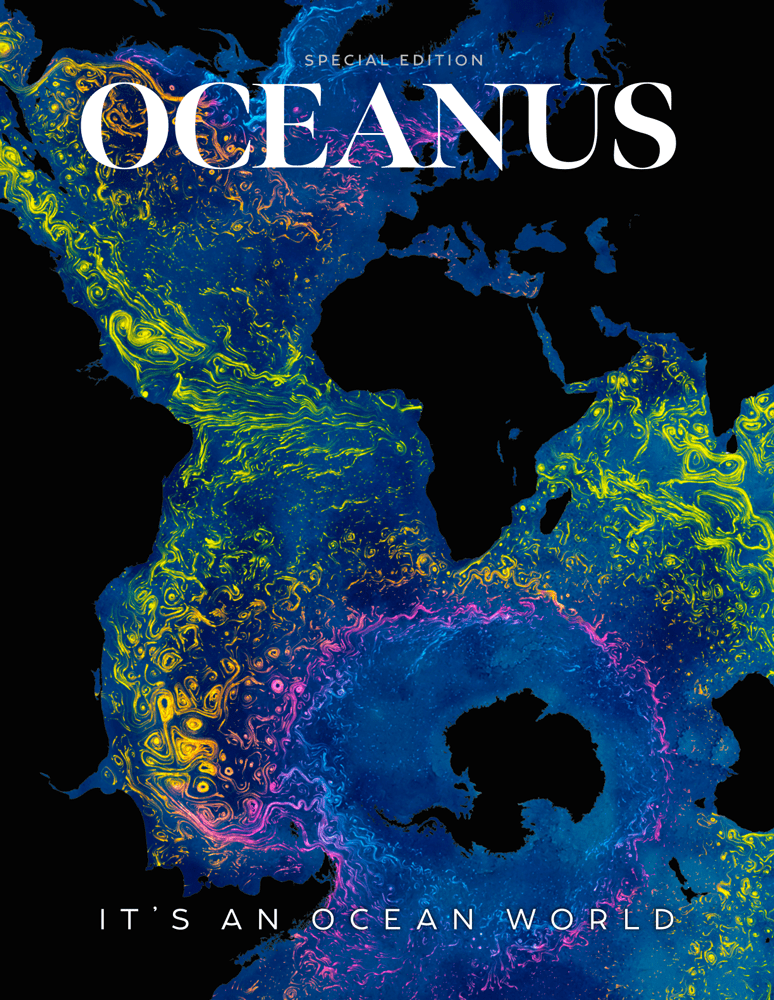

This article printed in Oceanus Winter 2025 - SPECIAL ISSUE

This article printed in Oceanus Winter 2025 - SPECIAL ISSUE

Estimated reading time: 8 minutes

In February 1977, the research vessel Knorr was 200 miles (322 kilometers) north of the Galápagos Islands. On board were geologists, geochemists, and geophysicists searching for evidence of hot water venting out of the ocean floor. The thriving ecosystem they encountered 8,000 feet (2,400 meters) below the surface would fundamentally change our understanding of life on this planet, and beyond it.

For 12 hours, the Knorr towed ANGUS—a newly designed search and survey platform equipped with strobe lights, cameras, and a temperature sensor—over the rugged volcanic terrain. ANGUS captured some 3,000 photos of the seafloor (some pictured below) and detected a single temperature anomaly, a spot where the water was unusually warm. When the researchers reviewed the images taken near the anomaly, they saw something that had previously been thought impossible—a lava flow covered with a field of white clams and brown mussel shells.

Over the course of the expedition, the researchers found the first known active hydrothermal vents, places where seawater interacts with magma-heated rocks, causing reactions that spew nutrients and chemicals into the surrounding area. Researchers descending in the submersible Alvin encountered eight-foot-long (2.4-meter) tube worms and football-sized clams thriving in an ecosystem fueled entirely by chemosynthesis.

“It created a whole new field of biological science,” says Susan Humphris, a scientist emeritus at WHOI who has spent her career studying the geology and geochemistry of hydrothermal vents. “Hundreds of new organisms have now been described from these vents.”

WHOI’s work is grounded in marine science and exploration, but the impacts of its discoveries and technologies often reach far beyond the ocean’s shores. The discovery of hydrothermal vents offered a new perspective on the origins of life. If microbes feeding off chemicals could form the basis of a food chain without sunlight or plants, then life could have evolved in places we had never even considered. It sparked a new search for life beyond Earth’s boundaries—inspiring missions to places as far away as the moons of Jupiter and Saturn.

It also spurred the development of new technologies, including remotely operated vehicles (ROVs) and deep-diving autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs), to explore the deep sea and collect samples. Some of the microbes collected at hydrothermal vents produce an enzyme that helps doctors test patients for infectious diseases. Others are being studied as sources of new anti-cancer drugs, antibiotics, and other treatments.

“The fact that you have a community of animals able to withstand very high temperatures has turned into something that is helping biomedical research,” says Humphris.

Developments at WHOI have had wide-ranging impacts that touch human health, infrastructure design, emergency response, national security, and much more. And the institution continues that work by protecting our coasts, developing robotic technologies and communication, leveraging artificial intelligence and machine learning, managing marine resources, and finding new ways to address climate change.

A legacy of innovation

Since the institution’s founding in 1930, WHOI scientists, engineers, and technicians have been dedicated to advancing knowledge of the ocean and its connections with the rest of the planet. And not just physical connections but human ones too—the ocean covers roughly 70 percent of the Earth, so it should be no surprise that it has shaped our society in addition to our environment. Breakthroughs in ocean science can be as much about helping people as they are about understanding and protecting the ocean.

During World War II, for example, oceanography made several key contributions to the Allied Forces. WHOI researchers developed instruments for measuring underwater shock waves and explosions, created seafloor maps to aid with submarine navigation and sonar transmission, and identified temperature differentials in the ocean that would bend sonar signals and allow submarines to hide from detection.

WHOI scientists also tackled the problem of biofouling—when organisms like barnacles and algae adhere to ships’ hulls, slowing them down and making them less efficient. Removing this unwanted growth traditionally required ships to be hauled out of the water and scraped down. But anti-fouling paints developed at WHOI have helped cut down on maintenance time and saved the U.S. Navy millions of dollars.

Oceanographic research is vital for national security, with acoustic monitoring and studies of ocean dynamics improving navigation, providing battlefield awareness, and aiding stealth communication. These technologies benefit coastal communities too: WHOI-designed floats, drifters, and other instruments monitor fluctuations in ocean temperature and currents that influence the strength and movement of hurricanes and other storms. Data from these instruments improve predictions and help provide early warnings for the people who live in harm’s way.

“The partnership between science and engineering is so important,” says WHOI chief scientist Dennis McGillicuddy. “Sometimes science leads technology, sometimes technology leads science, but that interface is fertile in so many ways.”

In many cases, a piece of technology was designed to solve a specific problem, such as how to sample chemicals in the scorching water near a hydrothermal vent. But these developments often end up serving a broader purpose.

When the Deepwater Horizon oil rig exploded and sank in 2010, unleashing an estimated 200 million gallons of oil into the Gulf of Mexico, WHOI scientists rushed to apply their tools and talents to an unfamiliar problem. They had expertise—and technology—that could help with the problem. Acoustic instruments that were initially built to track river flow rates and measure density deep underwater were put to work measuring just how much material was gushing out of the broken pipe. Tools designed to collect fluids and gases at hydrothermal vents helped determine the chemical composition of the oil at its source. AUV Sentry tracked the oil plume and current-mapping gliders helped predict where it would spread. Existing studies of deep water ecosystems in the Gulf helped measure less-obvious environmental impacts.

“Our response, and our ability to respond, to the Deepwater Horizon event demonstrates the value of basic research and the assets associated with that research, which might be vessels, vehicles, laboratory tools, techniques, sampling devices,” says Robert Munier, vice president of Marine Facilities and Operations, in 2011. “That really allowed us to respond in a way that was immediate and effective.”

The horizon ahead

The breadth and depth of scientific expertise at WHOI, combined with the engineering and ship operations that support access to the ocean all over the world, enable the institution to continue making groundbreaking discoveries and building tools that serve the global good. Researchers collaborating across the fields of chemistry, physics, biology, geology, physical oceanography, policy, and engineering are advancing research while helping to address some of the world’s biggest challenges.

WHOI is at the forefront of an effort to understand whether the ocean could be used to sequester more carbon from the atmosphere, to help slow the effects of climate change. This includes conducting experiments to support and expand natural carbon sinks, such as seagrass beds and saltmarshes, and to enhance the ocean’s alkalinity to counter ocean acidification and increase its ability to absorb carbon. The institution is currently planning field trials to measure the effectiveness and potential consequences of fertilizing areas of the ocean with iron, which could spark plankton blooms that would absorb carbon dioxide near the surface and sink it into deeper waters. Using this method, estimates suggest that fertilizing only a portion of the Southern Ocean could sequester as much as one gigaton of carbon per year—around 2.5 percent of current annual global emissions.

“WHOI is well positioned for this kind of research—which involves the biology of the ocean, the chemistry of the iron, the physics of ocean currents, and the tremendous technology required to measure the intended consequences and monitor the unintended consequences—because we have experts in all of these topic areas,” McGillicuddy says. WHOI senior scientist Ken Buesseler leads an international consortium, Exploring Ocean Iron Solutions, dedicated to providing answers to these questions so that society can make informed choices about what to do about the changing climate.

Scientists at the institution are working to address ocean-related human health issues as well, from forecasting the arrival of harmful algal blooms (and potentially reducing their frequency) to measuring the distribution of microplastics in the ocean and better understanding their health risks. They are developing new techniques to restore coral reefs, such as using sound cues to encourage coral larvae to repopulate degraded areas, and creating digital twins that will help scientists evaluate the solutions that work best for these ecosystems and the communities that rely on them.

WHOI is also making breakthroughs in underwater communications and autonomous vehicles. Recently, the U.S. Navy launched and recovered a WHOI-designed REMUS AUV through the torpedo tube of a Virginia-class submarine. It’s a “stunning technological achievement,” according to McGillicuddy, one that will allow the Navy to expand the capabilities of crewed submarines, using AUVs to assist in intelligence, mapping, and other missions.

The institution also shares its research capabilities with the larger oceanographic community by hosting scientific facilities. The National Ocean Sciences Accelerator Mass Spectrometry facility (NOSAMS) and the Northeast National Ion Microprobe Facility (NNIMF) help researchers date and analyze samples from all over the world; the Ocean Bottom Seismic Instrument Center (OBSIC) provides seafloor seismographs and technical support to help researchers study and monitor earthquakes, volcanos, and other dynamic processes; and the National Deep Submergence Facility (NDSF) provides access to a fleet of underwater vehicles, including the human-occupied vehicle (HOV) Alvin.

The result is a whole-system view of ocean science that facilitates new discoveries and provides opportunities for collaborations and innovation.

“We rely on the ocean for food, water, energy—all of these aspects which feed directly into human well-being and prosperity,” McGillicuddy says. The advances made at WHOI help ensure that these resources are available now and in the future, and provide the foundation for solutions to some of the biggest challenges on Earth.