Following the Polar Code

Crew of R/V Neil Armstrong renews their commitment to Arctic science with Advanced Polar Training

By Daniel Hentz | AUGUST 11, 2025

Captain Mike Singleton eased up the thrusters on the 400-foot icebreaker, USCG Polar Star, as it cleaved a path through the sea ice. “Nice and easy,” he thought.

A quarter mile ahead of him lay the mission: rescue of the 600-foot dry-bulk carrier M/S Ocean Giant, which days earlier had become beset by an Arctic ice field. It was Singleton’s job to free the vessel from the ice before the exit he’d just created froze over again. Within an hour, Polar Star had plowed its way around the stranded vessel, wedging itself between Ocean Giant and crimping sheets of sea ice. Frozen ridges began to pile up along Singleton’s starboard side. If he wasn’t careful, these ice peaks could amass too quickly and push back against his ship.

Forward, reverse, forward, reverse—the Polar Star found its rhythm, piercing the ice just a few meters (several yards) away from the carrier, and then using its stern and lateral thrusters to gently sweep away the pieces. Within two hours, a path was clear, and the Ocean Giant ignited its engine and found its point of egress.

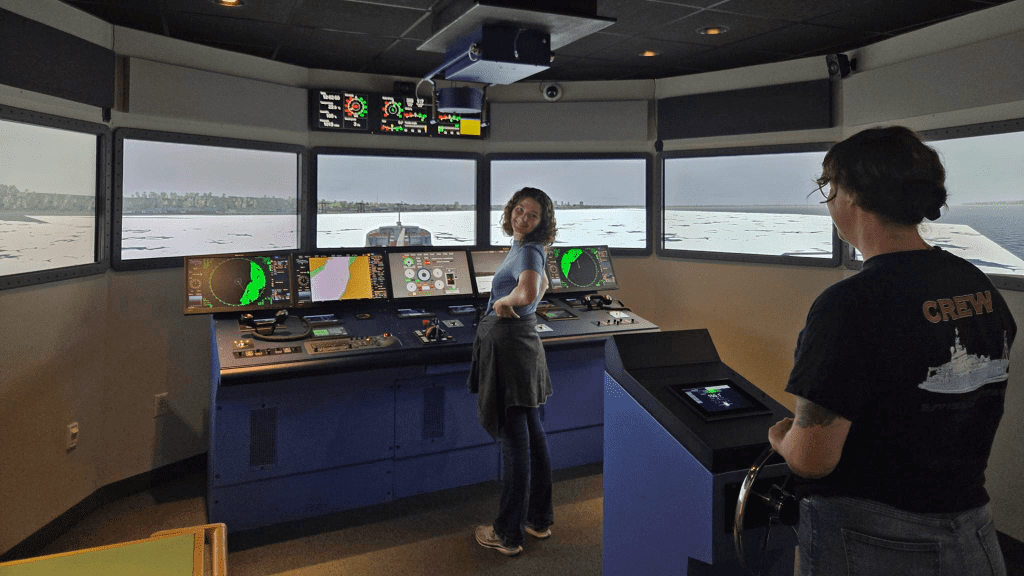

“Great job, Mike,” cracked a voice over the Polar Star’s radio. “Let’s take a break, and we’ll try a different simulation after lunch.” White lights blared on, and the computer screens that had served as windows on Singleton’s bridge flickered off. He had passed another virtual exercise.

R/V Neil Armstrong's third mate, Chrissy Hogan, and second mate Mariah Kopec-Belliveau drive an icebreaker in the simulation room at Maine Maritime Academy. (Photo courtesy of Mariah Kopec-Belliveau, © Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

For the past 18 months, the Office of Naval Research’s R/V Neil Armstrong and its WHOI-based crew have been working toward their Polar Code certification, a rigorous set of safety and environmental regulations set forth by the International Maritime Organization (IMO) for vessels operating in polar waters. Training simulations, like the one Singleton went through, came as part of the week-long National Science Foundation (NSF)-funded Advanced Polar Training required of Armstrong’s senior mariners. Singleton was one of six who completed the course, which helped earn the ship its polar certification from the American Bureau of Shipping in June of 2025.

“I've never had to break ice, certainly not like that,” said Singleton, R/V Neil Armstrong’s relief captain.

Sailing through polar waters isn’t for the faint of heart. A calm, sunny day can rapidly degrade into thick fog and a minefield of pack ice. These regions are so remote that vessels in distress may wait days before help arrives.

R/V Neil Armstrong isn’t an icebreaker, isn’t rated for dense ice fields, and doesn’t intentionally enter them. But its summer operations in areas like Baffin Bay and the Irminger Sea often require maneuvering around icebergs—frequently in low visibility.

The Polar Code expanded on the crew’s foundational maritime training. Trainees learned to interpret ice maps (or “Egg Codes”) to better assess conditions and make safer navigational decisions. WHOI’s Ship Operations also developed a new manual to guide Armstrong’s conduct in high-latitude waters.

Although government-owned vessels like the Armstrong aren’t required to carry Polar Code certification, WHOI pursued it voluntarily—as both an investment in safety and a signal of environmental responsibility.

“We were being asked to go to the Arctic more often, earlier in the year, and stay longer,” said WHOI Director of Ship Operations Paul Gallagher. “We chose to go above and beyond to be better prepared and reduce institutional risk.”

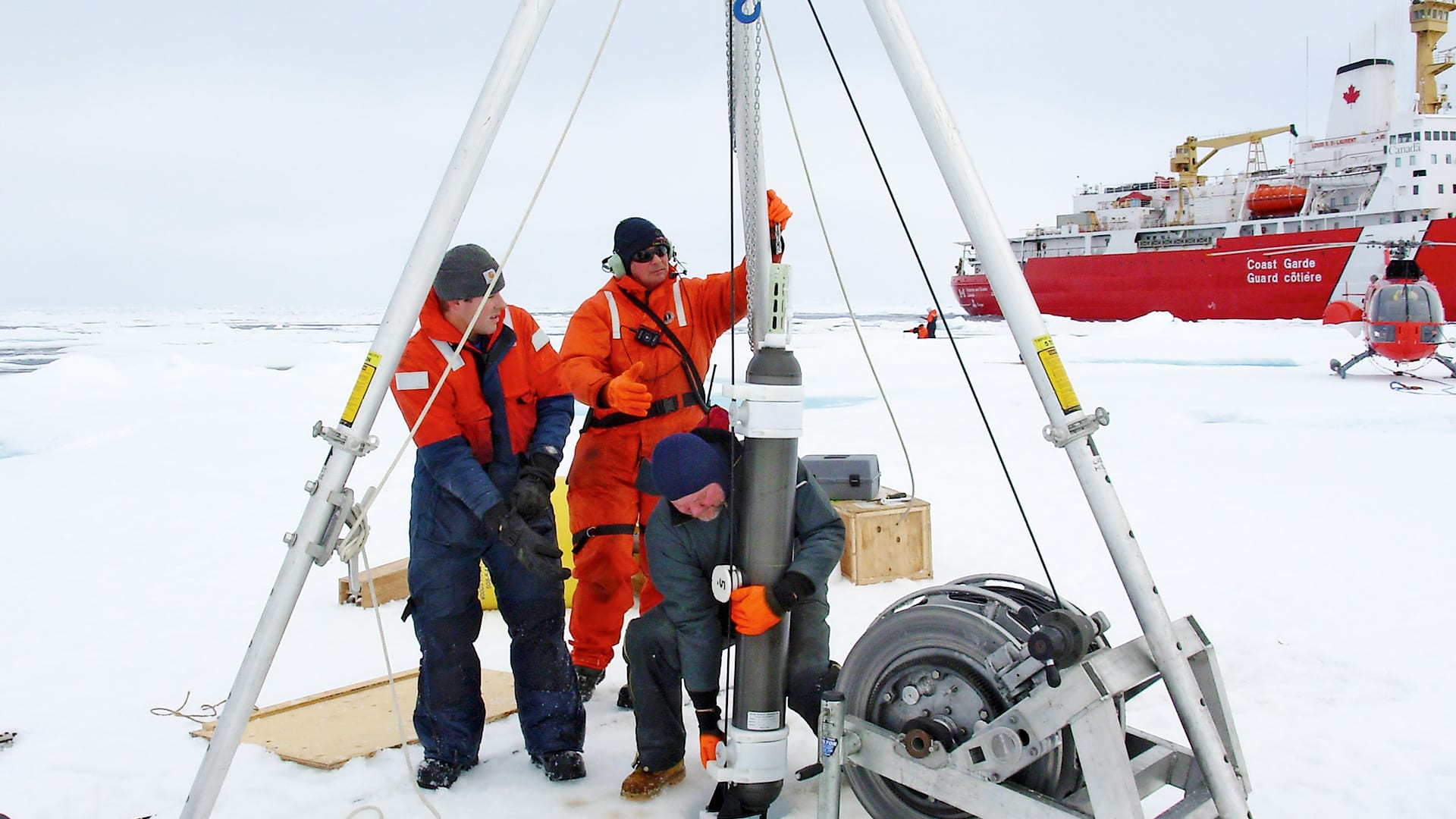

Each year, the Armstrong supports critical Arctic science missions, including long-term programs like the Ocean Observatories Initiative’s (OOI) Irminger Array and the Overturning in the Subpolar North Atlantic Program (OSNAP).

Newly trained, the ship’s crew says the Advanced Polar Training course deepened their readiness for the next cold water expedition.

“We’re experienced in these waters and know how to behave,” Singleton said. “Nothing—nothing will ever come close to being there in person.”

(Left to right) Chief Mate Diego Gevaudan, Relief Captain Mike Singleton, and Second Mate Mariah Kopec-Belliveau stand at the bridge of R/V Neil Armstrong after returning to Woods Hole from a recent research cruise. (Photo by Daniel Hentz, © Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)