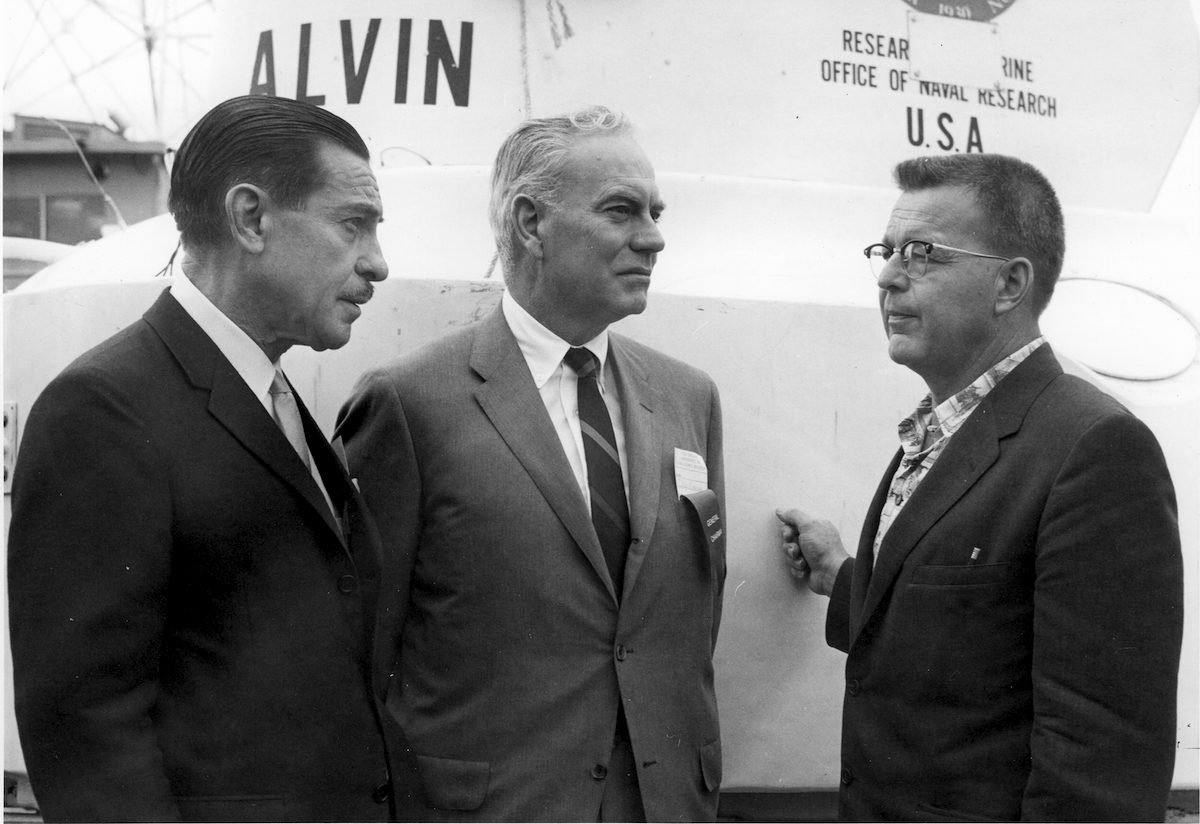

1915-1994

The father of Alvin

Allyn Vine, a WHOI engineer and geophysicist who helped pioneer deep submergence research and technology.

(Photo by Alfred H. Woodcock

© Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

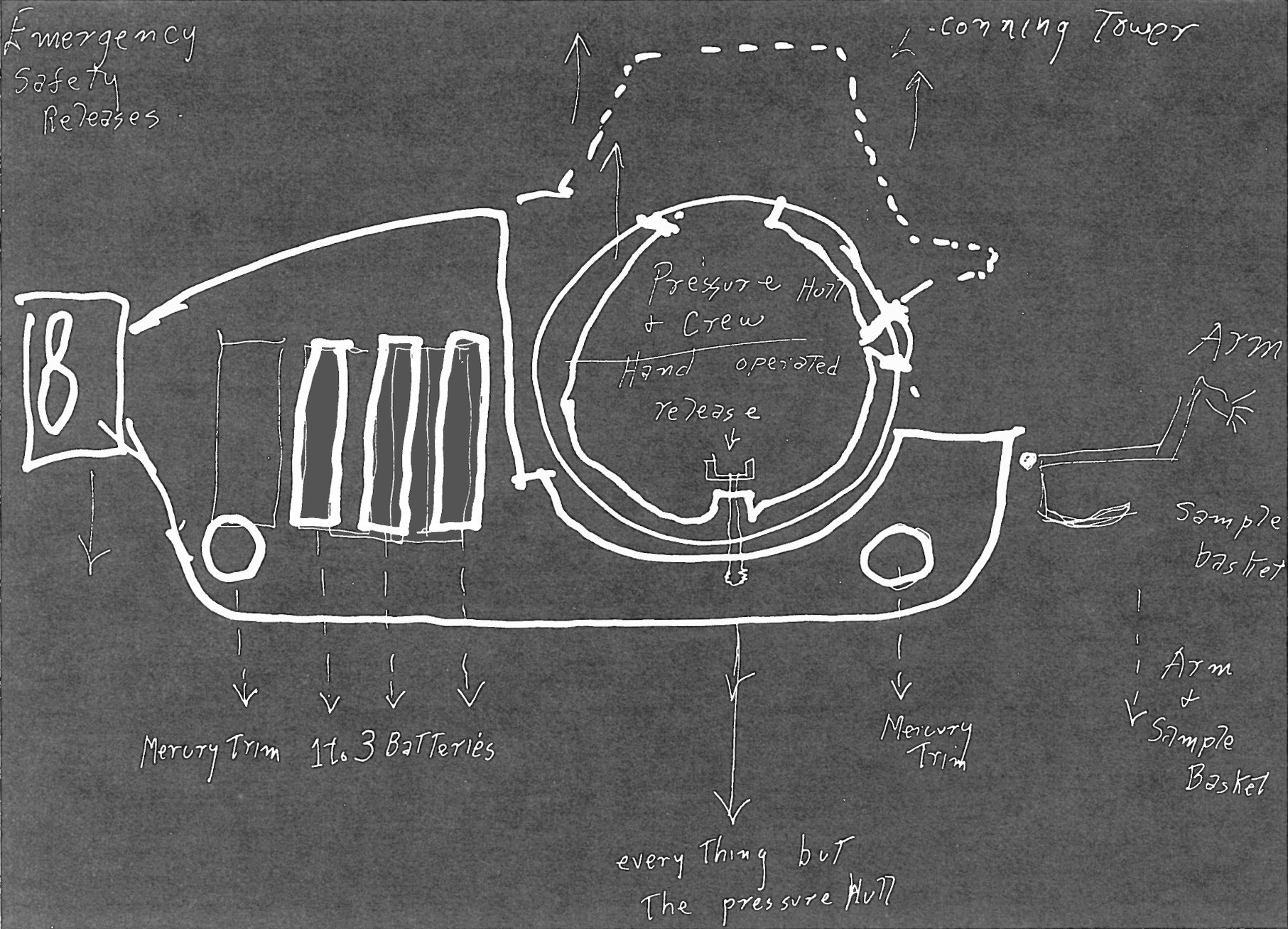

In the late 1950s, when the idea of a human-occupied submersible was just an engineering sketch, WHOI’s newly-formed Deep Submergence Group started calling it “Alvin”– after WHOI scientist Allyn Vine.

Vine was a vocal advocate for developing a scientific submersible to study the deep sea.

“A good instrument can measure almost anything better than a person can if you know what you want to measure,” Vine said at a symposium in Washington D.C. in 1956. “But people are so versatile, they can sense things to be done and can investigate problems. I find it difficult to imagine what kind of instrument should have been put on the Beagle instead of Charles Darwin.”

Vine’s argument for human-exploration of the ocean proved persuasive. The symposium, convened by the National Academy of Sciences and National Research Council, passed a resolution to create a national program that would develop vehicles capable of transporting humans to the deep sea. Six years later, in 1964, Alvin was ready to dive.

Alvin is one of Vine’s best-known projects, but he had a long and varied career as a physical oceanographer at WHOI. In the summer of 1940, Vine sailed into Woods Hole on the research vessel Atlantis as a Lehigh University graduate student working under Maurice Ewing. On that first visit, he persuaded WHOI to start its first machine shop, which he and colleagues used to build bathythermographs. The bathythermograph—which recorded ocean temperature versus depth–was so useful for ship and submarine operations during World War II that in 1948 President Harry Truman awarded then-WHOI President Columbus Iselin the U.S. Medal of Merit for its development. Iselin said the medal should have gone to Vine.

Vine worked closely with the U.S. Navy during the war years. His research included testing antifouling paints, studying the transmission of sound in the sea, developing underwater explosives, designing the first deep-sea cameras, making current and drift predictions to locate downed aviators on life rafts, and troubleshooting issues with submarines.

In peacetime, Vine threw himself into adapting war technologies for science, with a particular interest in exploring the deep sea. Vine wasn’t at his namesake’s commissioning ceremony, because he was deep beneath the surface of the Atlantic Ocean in the French submersible Archimede.

Further reading:

Down to the Sea for Science: 75 Years of Ocean Research Education & Exploration at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, by Vicky Cullen

Trailblazer in the Ocean: Alvin celebrates 50 years of pioneering accomplishments by Lonnie Lipsett, Oceanus

Allyn Vine, 79, Dies; Proponent of Submersibles by William Dicke, The New York Times