Making a splash on TikTok

Nate “The lumpfish guy” Spada brings ocean science to millions with amazing creatures and a sense of humor

Estimated reading time: 3 minutes

“Hey, aren’t you the lumpfish guy?”

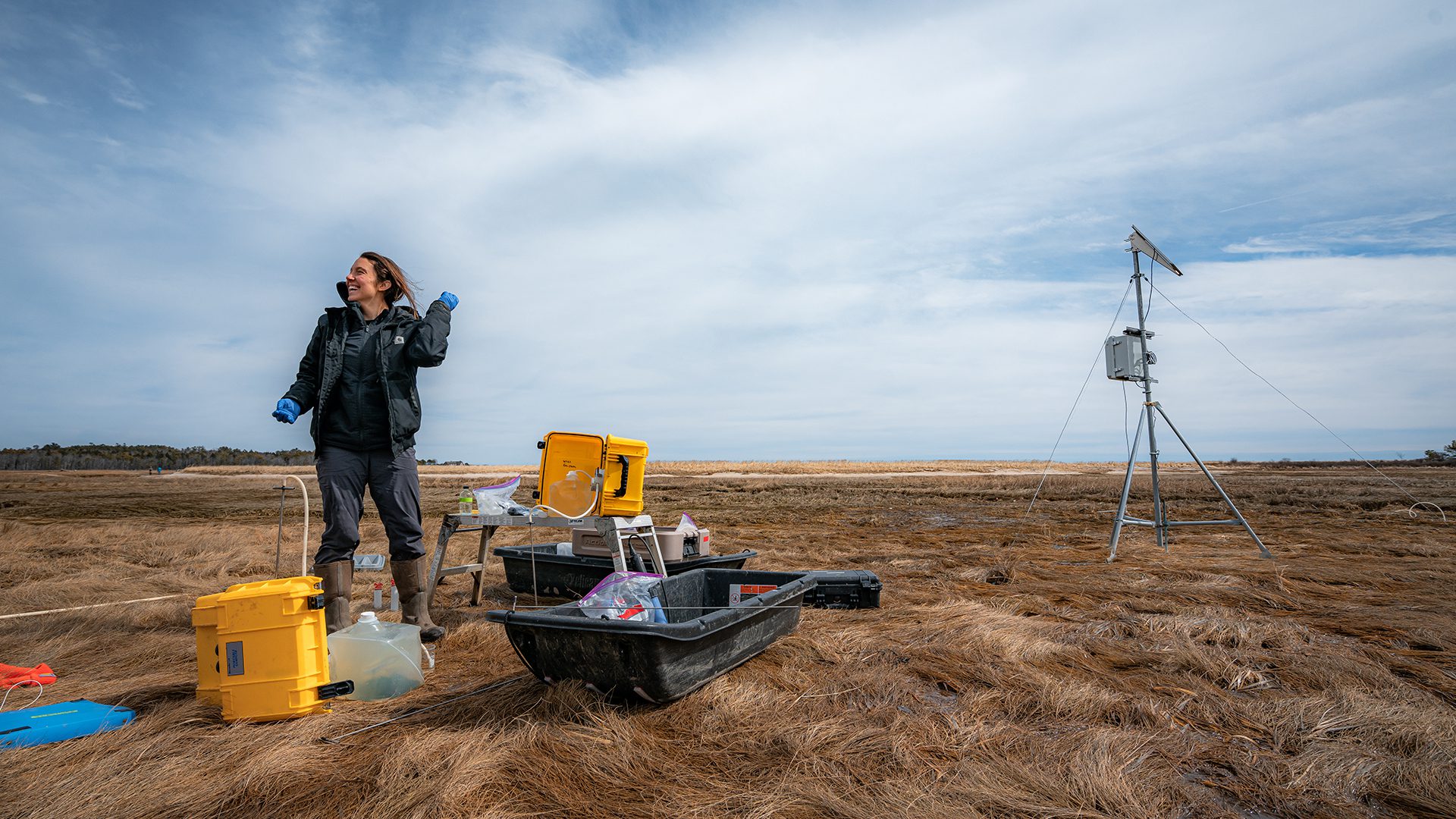

It’s a question that Nate Spada has heard time and time again when meeting people who have binged his wildly-popular series of ocean science videos on TikTok. Spada, a WHOI research assistant who studies harmful algal blooms (HABs) in the Anderson Lab, got his start on the planet’s fastest growing social platform in 2020 after his first video post—of a lumpfish (Cyclopterus lumpus)—went viral.

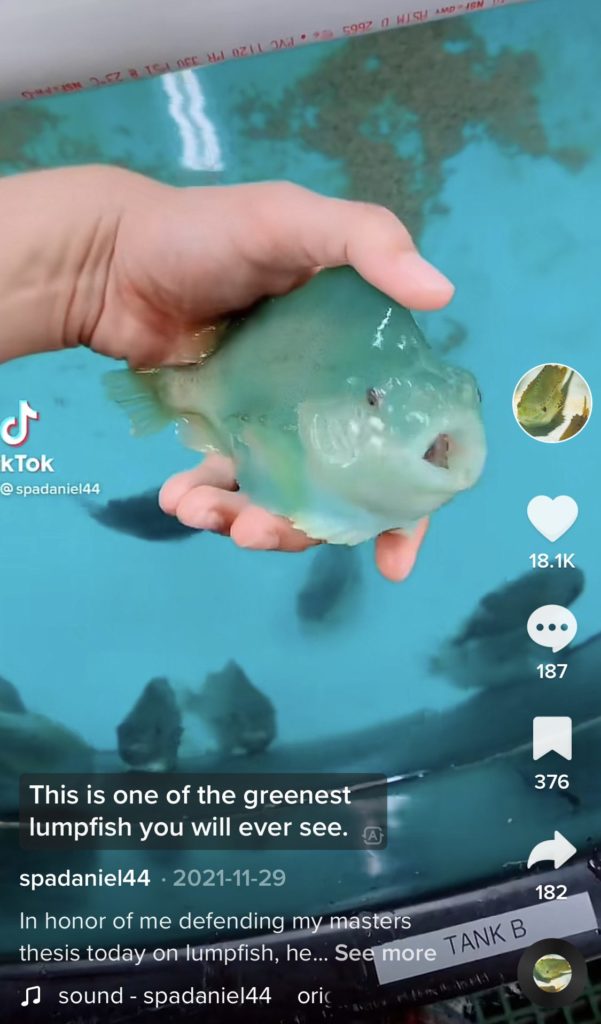

Spada's "Lumpfish" video on TikTok lead to his early success on the platform.

“There weren’t many videos of lumpfish posted on TikTok at the time, so it’s not something a lot of viewers had been exposed to,” says Spada. “But these basketball-shaped creatures are so charismatic with incredibly vibrant colors and a suction cup on their stomach. So, for my first post, I decided to create a video doing a David Attenborough impression looking at the lumpfish. It got something like 4.5 million views in the first month, and the rest was history.”

Beginners luck? Maybe. But today, Spada’s TikTok has 1.7 million followers—not a trivial number for a science-related feed. He says some of his success—maybe a good chunk of it, even—comes from a promise he made to his followers: if they got him to one million, he’d get a tattoo of a lumpfish. It’s currently on his right shoulder. But his popularity also seems predicated on his unique approach to video content, which he characterizes as “cool fish videos with a funny flair.”

“My number one goal is to educate general audiences about science and the ocean,” Spada says, “but I try to do it in a funny and sometimes sarcastic way, which I think can be more engaging for people. There’s no reason you can’t laugh and learn at the same time.”

Spada thinks of his videos as virtual journeys that viewers can take with him to experience and discover new things. In one series, he pulled lobster traps from the University of New Hampshire’s (UNH) marine research pier just to see what was inside and then explained what each of the creatures were. In another, he walked the beach flipping over rocks to see what was underneath. Since it only takes him about ten minutes to produce a video, he sometimes creates them while he’s on the job.

“I might be in the HABs lab transferring a culture of algae and see some really cool color that strikes me,” he says. “I’ll just film and post it right then and there.”

Spada inspects a horseshoe crab in the wet lab at WHOI. (Photo by Daniel Hentz, © Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

Being a TikTok influencer, however, isn’t without its headaches. Spada occasionally gets “backlash and hate” in viewer comments, where people might criticize his animal handling skills, or suggest that fish shouldn’t be used for scientific research. He used to take the negative stuff to heart and comment back, but over time he realized there was no winning at that game.

On the flipside, Spada’s influencer status has helped inspire a number of his viewers. “I had to make a goodbye video for the Coastal Marine Lab at UNH when I graduated and in it, I said that I hope that I made a difference,” he says. “In my DMs and comments section, people were saying that I really did, and added comments like, ‘I want to go back to school now and become a marine biologist.’ It made me feel great.”

Today, Spada is starting to see signs of the platform evolving in a way where more older people are using it learn. “I know a bunch of people my generation and older—even my dad—that are now getting involved in the app because they want to learn about science, but they don’t necessarily want to read through research papers or have someone explain things to them. It’s easier for them to just watch a short video.”

TikTok may be starting to shed some of its “teenage dance video” stigma, but still, less than half of current TikTok users are wedged within the 18-34 age bracket. But Spada is hopeful that in the future, he and others using the tool to communicate science will have a much broader pool of viewers to reach.

“Once more people who are interested in marine science start going on TikTok and interacting with the app, their algorithms will be trained to get more of these videos,” says Spada. “That’s when the real impact will happen and we’ll get that larger audience that ocean science deserves.”