Salps Catch the Ocean’s Tiniest Organisms

Oh, what remarkably built internal mucus nets they weave

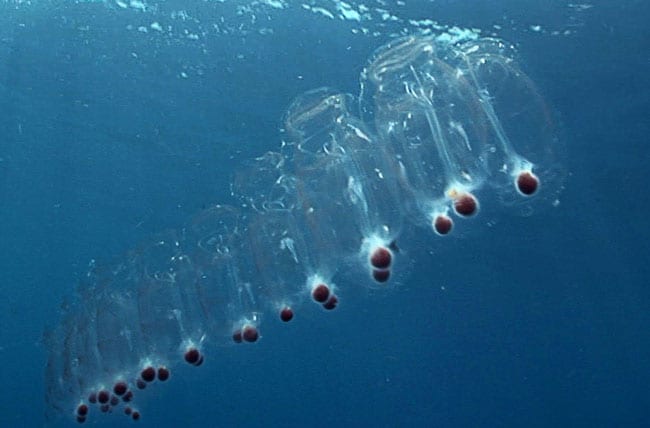

Salps are sometimes called “the ocean’s vacuum cleaners.” The soft, barrel-shaped, transparent animals take in water at one end, filter out tiny plants and animals to eat with internal nets made of mucus, and squirt water out their back ends to propel themselves forward.

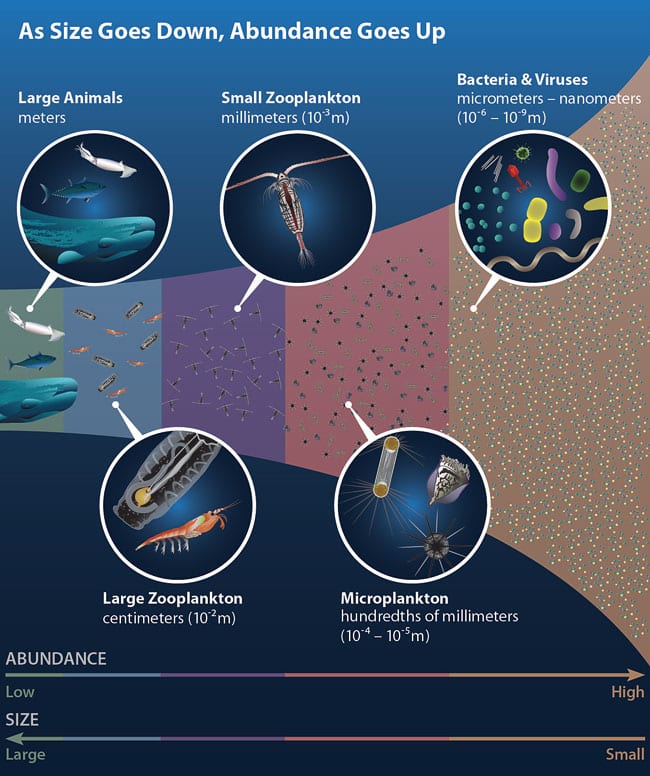

In a surprising new finding, scientists at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology showed that the salps’ nets are remarkably engineered to catch extremely small particles that scientists assumed would easily slip through the 1.5-micron holes in the nets. (A micron is a millionth of a meter, or 10-6m.) Their discovery revealed a previously unsuspected biological mechanism that helps operate the marine food web and also removes the greenhouse gas carbon dioxide from the upper ocean.

In experiments at the Liquid Jungle Lab in Panama, Kelly Sutherland, then a graduate student in the MIT/WHOI Joint Program, and colleagues observed salps in water containing different-size food particles in concentrations representing the real ocean. The particles were smaller, around the same size as, and larger than the mucus net openings.

Sutherland found that “80 percent of the particles that were captured were the smallest particles offered in the experiment,” she said. “It’s counterintuitive. Your intuition tells you that the salps should capture particles larger than the holes in their nets. They catch those things—and things that are smaller than the holes.”

The key is that the mucus strands are sticky. “It’s like dust blowing through a window screen; any dust that hits the window screen strands sticks to them,” said Sutherland, now a postdoctoral scholor in bioengineering at the California Institute of Technology.

That allows salps to “consume particles spanning four orders of magnitude in size,” said Laurence Madin, biologist and director of research at WHOI, and Sutherland’s doctoral advisor. “This is like eating everything from a mouse to a horse.” Sutherland, Madin, and Roman Stocker of MIT’s Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering reported their findings in the Aug. 9 issue of Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The finding is important for a number of reasons. First, it helps explain how salps—which can exist either singly or in “chains” that may contain a hundred or more individuals—can survive in the open ocean, their usual habitat, where the supply of larger food particles is low. “Their ability to filter the smallest particles may allow them to survive where other grazers can’t,” Madin said.

Second, and perhaps most significantly, it enhances the importance of the salps’ role in cycling carbon from the atmosphere into the deep ocean. As they eat, they consume a very broad range of carbon-containing particles and efficiently pack the carbon into large, dense fecal pellets that sink rapidly to the ocean depths, Madin said.

“This removes carbon from the surface waters,” Sutherland said, “and brings it to a depth where you won’t see it again for years to centuries.” And more carbon sinking to the bottom reduces the amount and concentration of carbon in the upper ocean, letting more carbon dioxide enter the ocean from the atmosphere, explained Stocker.

The research, funded by the National Science Foundation and the WHOI Ocean Life Institute, “does imply that salps are more efficient vacuum cleaners than we thought,” Stocker said. “Their amazing performance relies on a feat of bioengineering—the production of a nanometer-scale mucus net—the biomechanics of which still remain a mystery.” (The net strands are mere nanometers, or billionths of a meter, thick.)

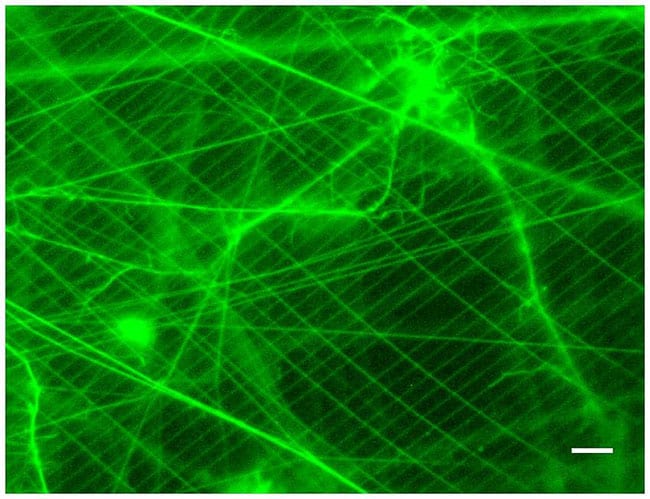

A big step in the research was getting accurate images of the salps’ nets, to get precise measurements of the size and pattern of holes within them. Previously, scientists had to dry and freeze the nets to take images. “That distorts something as fragile as a mucus net,” Sutherland said. “We wanted accurate measures while the nets were wet.”

To make the first images of “live” mucus nets in salps, Sutherland inserted thin pieces of glass (slide cover slips) into living, swimming salps’ body cavities, letting the mucus net adhere to it. “You can never tell if a salp has a net in it or not,” she said, “because it’s transparent in a transparent animal.”

She retrieved nets and, working with Anthony Moss, a marine biologist at Auburn University, she stained them with a fluorescent dye that revealed the meshes in all their glorious precision and regularity.

Slideshow

Slideshow

- Kelly Sutherland, now a postdoctoral scientist at CalTech, and Larry Madin, her doctoral advisor at WHOI, studied the feeding and locomotion of salps, such as this one preserved in a jar. With MIT professor Roman Stocker (not shown), they showed that salps are able to catch and eat some of the smallest particles in the ocean. (Photo by Tom Kleindinst, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

- Transparent tubular animals, salps produce a feeding net of mucus that hangs inside their bodies. As they swim, they catch food particles on the net. (Photo by Larry Madin, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

- The green-stained mucus feeding net of a salp, photographed under a microscope, reveals amazingly regular openings only about 1.5 microns (1.5 millionth of a meter) on a side. The net catches particles that don't fit through the mesh, but its strands also catch much smaller particles, down to the size of bacteria.

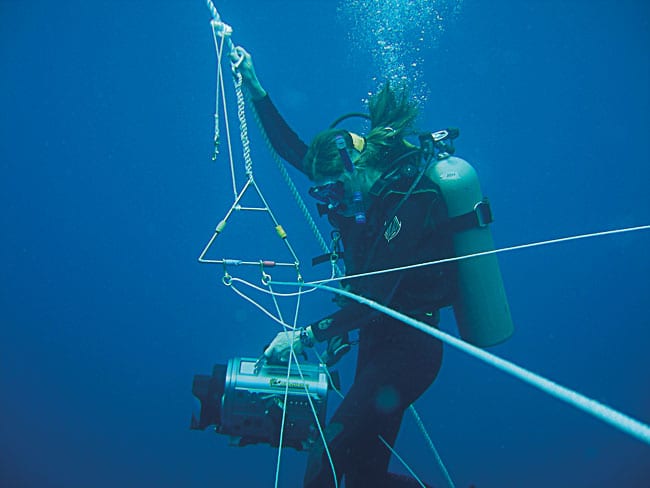

(Photo by Kelly Sutherland, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution) - Working on living salps requires an ocean-going ship or a lab near open ocean water. Kelly Sutherland, while a graduate student at WHOI, did her research at the Liquid Jungle Lab in Panama. There, deep water is not far from shore, and Sutherland could collect them by scuba diving. (Photo by Andrew Gray, UC Santa Cruz)

- Salps can be connected in long chains of identical animals, all swimming together. In this way, they feed efficiently by filtering food from the water they swim through. (Photo courtesy of Kelly Sutherland, © Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

- Kelly Sutherland doing an experiment with living salps in the Liquid Jungle Lab, Panama. She fed them particles of known sizes to determine what their feeding nets could capture. (Photo by Alexandra Techet, Massachusetts Institute of Technology)

- Kelly Sutherland and Larry Madin study a variety of gelatinous (jelly-like) ocean animals.

(Photo by Tom Kleindinst, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution) - Marine life ranges in size from viruses, at nanometers (10-9m), to whales tens of meters long. The bigger the organism, the fewer there are in the ocean. In general, creatures in one size range prey on the next range below them. But salps' unique feeding nets catch not only the next size down, but also some of the tiniest and most abundant cells in the sea.

Video

Related Articles

- Edie Widder: A light in the darkness

- Five times the ocean helped us learn about the human body

- Mesobot, Follow that Jellyfish!

- Tiny Jellyfish with a Big Sting

- Journey Into the Ocean’s Microbiomes

- Mysterious Jellyfish Makes a Comeback

- Tiny. Ubiquitous. Vital. Delicate. Vulnerable.

- Bacteria Hitchhike on Tiny Marine Life

- Exhibit Spotlights Sea Butterflies

Featured Researchers

See Also

- Introduction to Salps from Dive & Discover

- Dye Sheds Light on Jet-Propelled Salps A graduate student reveals locomotion in the ocean [from Oceanus magazine]

- Transparent Animal May Play Overlooked Role in the Ocean from Oceanus magazine

- Larry Madin, director of research, WHOI

- Professor Roman Stocker, MIT

- Liquid Jungle Lab