Robot Paints Stunning Map of Deep-sea Volcano

Sonar images reveal submerged Pacific Ocean volcano in glorious detail

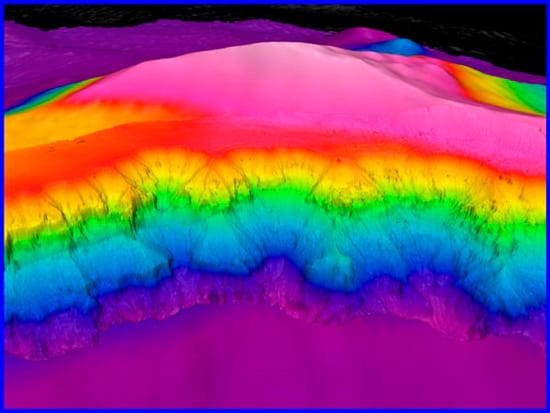

Painting with sonar, each brushstroke a “ping” of sound reflected off the seafloor, the robotic underwater vehicle called ABE created a masterpiece of a landscape—one that is submerged about a mile deep in the Pacific Ocean.

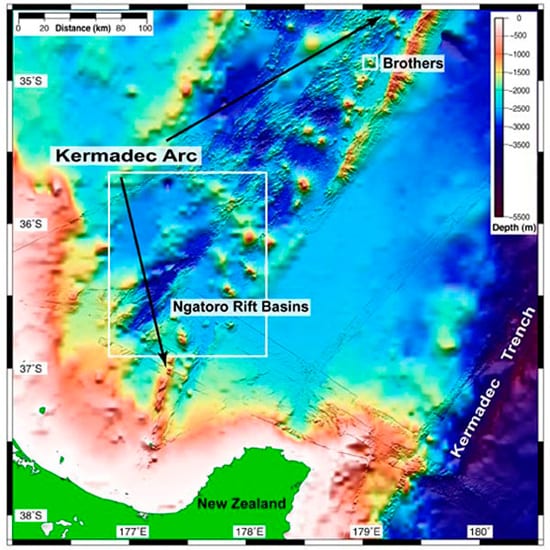

On an international expedition last summer, scientists from Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) turned the sonar data collected by ABE (the Autonomous Benthic Explorer) into a richly textured three-dimensional seascape of the cantankerously cratered Brothers Volcano, roughly 290 nautical miles (537 kilometers) northeast of New Zealand.

“When we first gazed at the map of the northwest slopes of Brothers volcano tacked up on the lab wall by ABE’s lead engineer Dana Yoerger, we thought that our eyes were playing tricks on us,” wrote Bob Embley, the expedition’s chief scientist and a geophysicist from NOAA’s Pacific Marine Environmental Laboratory in Oregon. “The clarity of the fine-scale features was absolutely stunning.”

“The map that ABE produced of the caldera at Brothers is astounding, and is like viewing the detailed topography of White Island (one of New Zealand’s largest continental volcanoes), if you were to walk around it on foot,” Embley wrote on the NOAA Ocean Exploration Web site. The three-week expedition last July and August aboard the German research vessel Sonne also included scientists from New Zealand and Germany.

Above and into the caldera

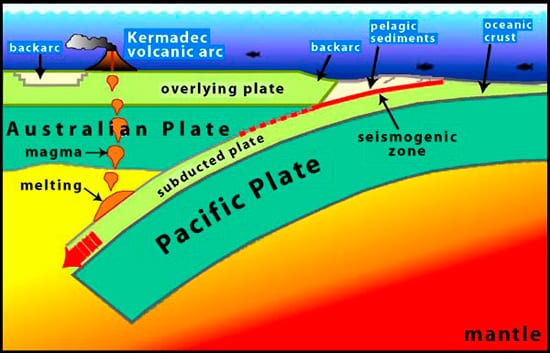

Brothers volcano is one of a string of 33 volcanoes in the Kermadec arc, part of the Ring of Fire that forms a necklace of volcanoes around the entire Pacific Ocean. It forms where the mammoth Pacific tectonic plate plummets beneath the Australian tectonic plate in a process called subduction. Some 125 feet (200 kilometers) beneath the seafloor, subducting materials begin to melt, producing hot, buoyant magma that rises and periodically erupts through the overlying Australian Plate to form the volcanoes that make up the Kermedec arc.

The eruption that created Brothers Volcano was intense and explosive, creating steep walls whose slopes average 45 degrees. “But that average doesn’t tell you the whole story,” Yoerger said, “because you’ll get a steep drop followed by a modest drop followed by a sheer drop. Its highest point is close to three John Hancock buildings tall in Boston terms. Imagine something that steep and rough. If we could have seen the terrain, we would have been pretty scared.”

At the top, the steep walls caved in to form a caldera, or crater, as wide as Mount St. Helens’. The insides of the caldera walls are rugged, with ampitheater-sized slumps of old rock sliding into the crater.

“It was pretty impressive terrain,” said Yoerger, who led a three-member ABE team from WHOI that included Andy Billings and Al Duester. “There were lots of things that could have gone wrong.”

For example: “On the first dive, ABE sprang a leak,” Yoerger said. Billings, Duester, and the ship’s crew dismantled ABE “down to every wire and bolt” and in one day fixed the corroded connector that caused the leak. “It was one of the handful of spectacular at-sea fixes I’ve ever seen,” Yoerger said.

“We’re not shy about throwing the vehicle [ABE] into really rugged terrain,” Yoerger said. “It did fine and never came close to colliding into anything. It’s perfectly comfortable—if that’s the right word to apply to a robot—working in that kind of steep terrain.”

Twin volcanic peaks

ABE completed eight dives totaling 96 hours. It “flew” in densely packed lines to cover the entire volcano, maintaining a constant height just above the volcano’s rugged, ever-changing contours. The ability to gather sonar data right near the seafloor translates into higher precision—much the way hiking a mountain provides more details than flying high above it. Whereas older sonar maps of Brothers had a resolution of football field-sized features, the new map enables scientists to see features the size of a beefy linebacker or two.

Also equipped with chemical, temperature, and other sensors, ABE located hydrothermal vents that emit hot, mineral-rich fluids from the seafloor. When the hot fluids mix with cold ocean water, metals precipitate on the seafloor. Hydrothermal venting is particularly intense on two volcanic peaks, fed by fresh eruptions, that are forming inside Brothers’ caldera. They were discovered in 1998 on another Sonne expedition by Cornel de Ronde, a geologist at the Institute of Geological and Nuclear Sciences in New Zealand, who returned to Brothers on the 2007 expedition.

De Ronde said these areas, which lie within New Zealand’s exclusive economic zone, may contain aggregations of copper, zinc, lead, and gold that are large enough to be mined.

“If we can understand the evolution of the hydrothermal venting inside Brothers, it will enable us to transport this understanding to other submarine volcanoes along the Kermadec Arc,” said de Ronde. “This is the first time anywhere in the world that a submarine arc volcano like Brothers has been mapped and surveyed for hydrothermal venting at such incredibly detailed scale.”

When Yoerger brought down the final map of the Brothers volcano caldera, “we just sat there in silence for a few seconds staring at it, knowing that we were probably the first to see a submarine volcanic caldera as it really ‘is’,” Embley wrote in the final log for the expedition Web site.

“Well, I was never good at drawing or painting as a kid,” Yoerger responded. “I guess I need a few technological aids to make pretty pictures. I can’t do a thing with water colors, but I can do it with a robot—and the ABE team.”

The 2007 New Zealand American Ring of Fire exploration expedition was a collaboration among GNS Science in New Zealand, IFM-GEOMAR of Germany, the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Ocean Exploration Program, and Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution.

Slideshow

Slideshow

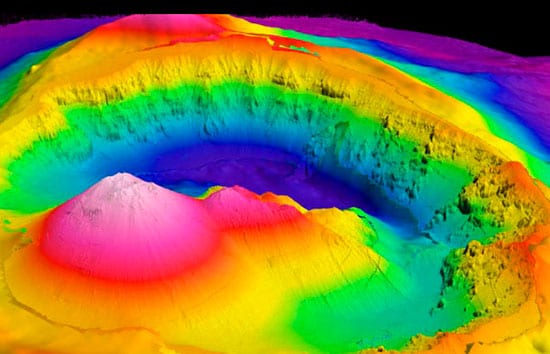

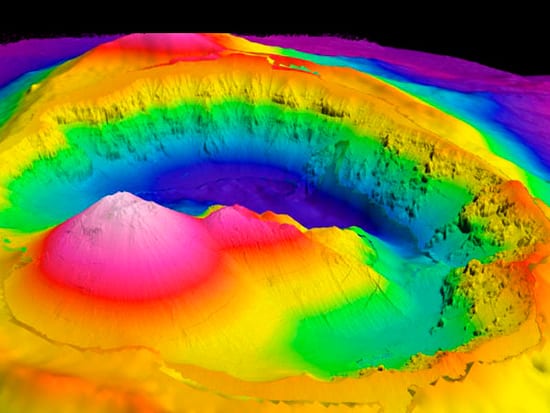

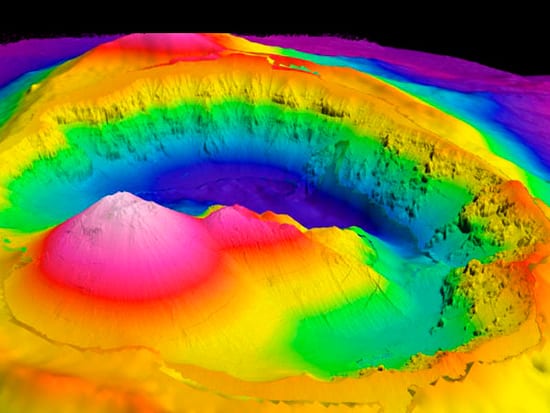

The deep-sea robot ABE (Autonomous Benthic Explorer) created this map of the active underwater Brothers Volcano. (See fly-through movies below.) This view looks from the south into the crater at the summit of the volcano, the site of recent eruptions and ongoing hydrothermal venting. The caldera has two volcanic cones, the smooth one in the left foreground rises about 350 meters (1,150 feet) above the caldera floor to a depth of about 1,100 meters (3,600 feet) below sea surface. A smaller cone to the right, which is probably older but still has an intense hydrothermal system at its summit. (Image courtesy of New Zealand American Submarine Ring of Fire 2007 Exploration, NOAA Vents Program, NOAA-OE.)

The deep-sea robot ABE (Autonomous Benthic Explorer) created this map of the active underwater Brothers Volcano. (See fly-through movies below.) This view looks from the south into the crater at the summit of the volcano, the site of recent eruptions and ongoing hydrothermal venting. The caldera has two volcanic cones, the smooth one in the left foreground rises about 350 meters (1,150 feet) above the caldera floor to a depth of about 1,100 meters (3,600 feet) below sea surface. A smaller cone to the right, which is probably older but still has an intense hydrothermal system at its summit. (Image courtesy of New Zealand American Submarine Ring of Fire 2007 Exploration, NOAA Vents Program, NOAA-OE.)- A close-up view of the northwestern wall of Brothers volcano shows ampitheater-sized slumps of old rock that have slid toward the seafloor. The 2-meter-resolution imagery taken by ABE (in the foreground) is overlaid on 25-meter-resolution imagery taken by the ship-based EM300 sonar. (Image created by the NOAA Vents Program.)

- Andy Billings, an engineer from Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, makes final checks on the ABE autonomous vehicle before its first dive at Brothers volcano. (Photo courtesy of New Zealand American Submarine Ring of Fire 2007 Exploration, NOAA Vents Program)

- The New Zealand American Submarine Ring of Fire 2007 expedition aboard the research vessel Sonne targeted the Brothers Submarine Volcano and the Ngatoro Rift Basins, north of New Zealand.Bathymetry data are: satellite-derived (bottom, 3500-meter resolution); EM300 (top, along the arc, 30-meter resolution). Plate tectonic features are also indicated. (Image courtesy of satellite-derived bathymetry from Sandwell and Smith, EM300 bathymetry data courtesy of Pacific Marine Environmental Laboratory, the Institute of Geological & Nuclear Sciences, NOAA Vents Program and NOAA-OE.)

- In a collision of tectonic plates, the Pacific Plate is being subducted beneath the Australian Plate, bringing along oceanic crust and a thin veneer of pelagic sediment. Behind the subduction zone, the crust of the Australian Plate is extended, forming backarc basins. At certain depths, usually around 200 kilometers (about 100 nautical miles), subducted materials melt, producing magmas that rise buoyantly to pond in the overlying mantle wedge and periodically erupt on Earth's surface as lavas, forming arc volcanoes. (Illutration courtesy of Institute of Geological and Nuclear Sciences Ltd.)

- Dana Yoerger developed the Autonomous Benthic Explorer with Al Bradley and now heads the ABE team. Yoerger is a scientist in Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution's Department of Applied Ocean Physics and Engineering. (Photo by Tom Kleindinst, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

Video

Related Articles

- How did the ocean remain so quiet during Tonga’s eruption?

- Spock versus the volcano

- In Search of the Pink and White Terraces

- ROV Jason Images the Discovery of the Deepest Explosive Eruption on the Sea Floor

- Undersea Asphalt Volcanoes Discovered

- Deeply Submerged Volcanoes Blow Their Tops

- Plumbing the Plume That Created Samoa

- New Wrinkles in the Fabric of the Seafloor

- Jason Versus the Volcano

Featured Researchers

See Also

- New Zealand American Submarine Ring of Fire 2007 Expedition from the NOAA Ocean Explorer Web site

- ABEThe Autonomous Benthic Explorer from Oceanus magazine

- NOAA's Pacific Marine Environmental Laboratory

- GNS Science New Zealand

- IFM-GEOMAR The Leibniz Institute of Marine Sciences at the University of Kiel

- AUV ABE/Sentry from the WHOI National Deep Submergence Facility Web site

- The ABE Web site