MORE TO KNOW

Reconstructing the Bering Sea’s stormy past

Researchers help Bering Sea indigenous communities understand the past and plan for future

By Evan Lubofsky | May 10, 2023

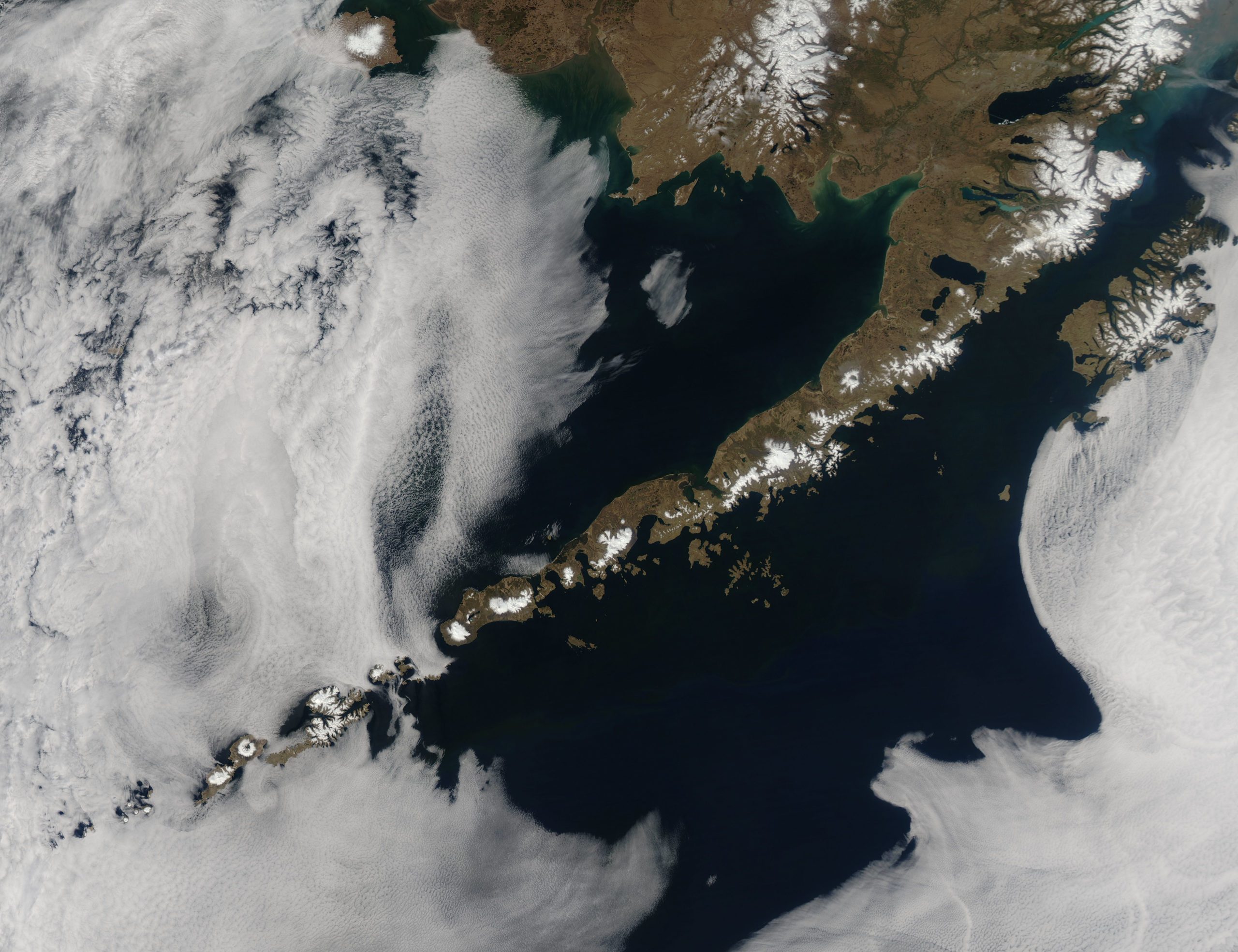

Image by NASA/GSFC/Jeff Schmaltz/MODIS Land Rapid Response Team

In the Bering sea, rapid climate change may be causing more intense storms, flooding, and erosion. To better understand how storm scenarios will play out in the future, researchers from WHOI and their colleagues travelled down the Aleutian Islands chain on the R/V Sikuliaq during the summer of 2022 to reconstruct ancient storms in the Bering Sea.

“The Aleutian Islands are an ideal study site because they experience storms, landslides, tsunamis, and tectonic activity,” said Kelly McKeon, a geologist in the Donnelly Lab at WHOI. “And they are good at recording these events over time in sediments deposited.” (Drone footage by Sarah Betcher, Farthest North Films)

Researchers prepare to collect ancient sediment samples from the seafloor using tubes like the one shown here. Once the tubes are full of sediment, the cores will provide a prehistoric record of extreme events that can be used to understand how storms and climate have changed together in the Bering Sea over the last several thousand years. (Photo by Sarah Betcher, Farthest North Films)

Driving tubes into the seafloor was a team effort between the ship’s crew, scientists, technicians, and members of the Qawalangin Tribe of Unalaska. The science team collected cores as long as 20 meters (65 feet) by vibrating these tubes into the sediment. The resulting cores contain a record of deposition spanning thousands of years of storm history on the island of Unalaska. (Drone footage by Sarah Betcher, Farthest North Films)

WHOI senior scientist Jeff Donnelly (white hard hat), UNCW graduate student Chris Blanco (orange hard hat), and MIT-WHOI Joint Program student Laura Barnett (blue hard hat) help transport a sediment-packed core to a stand where it will be sliced into smaller sections to be shipped back to the lab at WHOI.

“The limited written record from the region means that little is known regarding the history of storms in the Bering Sea before the 20th century,” Donnelly said. “Thus, we have a poor understanding of the risks related to intense storms and how those risks may be changing. This study aims to remedy this by expanding our knowledge of past intense storms back many centuries and even millennia using the sedimentary record.” (Photo by Sarah Betcher, Farthest North Films)

Before sediment coring begins, scientists survey the bathymetry of the bay and choose their coring locations with the help of a sub-bottom profiler. Native Alaskan Piama Oleyer (back right) joined the team as an Indigenous expert on the natural history of Unalaska. Kelly McKeon (front right) and UNCW coastal geologist Andrea Hawkes (left) look at output from the sub-bottom profiler, which tells them how much sediment has accumulated in the basin and detects obstructions that might impede coring. (Photo by Sarah Betcher, Farthest North Films)

The Sikuliaq was sometimes too large to provide access to sites behind shallow sills, so the research team deployed a pontoon boat to core some of these difficult-to-access locations. Specifically designed for sediment coring, the R/V Charlena has a moon pool cut into the deck, making it easy to collect cores through the center of the vessel. (Photo by Sarah Betcher, Farthest North Films)

Because the Aleutian Islands are an active plate boundary, vertical land motion has created a complex sea-level history for the region. As part of the research, the science team also collected sediments on land to help reconstruct this history. They selected sites like this one based on satellite imagery that showed preserved beach ridges from ancient shorelines.

“To know how long an area has been accumulating sediment, you need to know how long it was sitting under the ocean for,” said McKeon. (Photo by Sarah Betcher, Farthest North Films)

Chris LaClair, a research specialist at UNCW, deploys a weather station at one of the coring locations. Instruments like weather stations and wave buoys will help the researchers correlate weather conditions with types of sediment deposits that may be found at these sites. Once the storm history for the region is reconstructed, researchers will compare it to reconstructions of past weather and climate conditions to understand how different aspects of climate, such as sea ice cover, might affect storm variability in the Bering Sea. (Photo by Sarah Betcher, Farthest North Films)

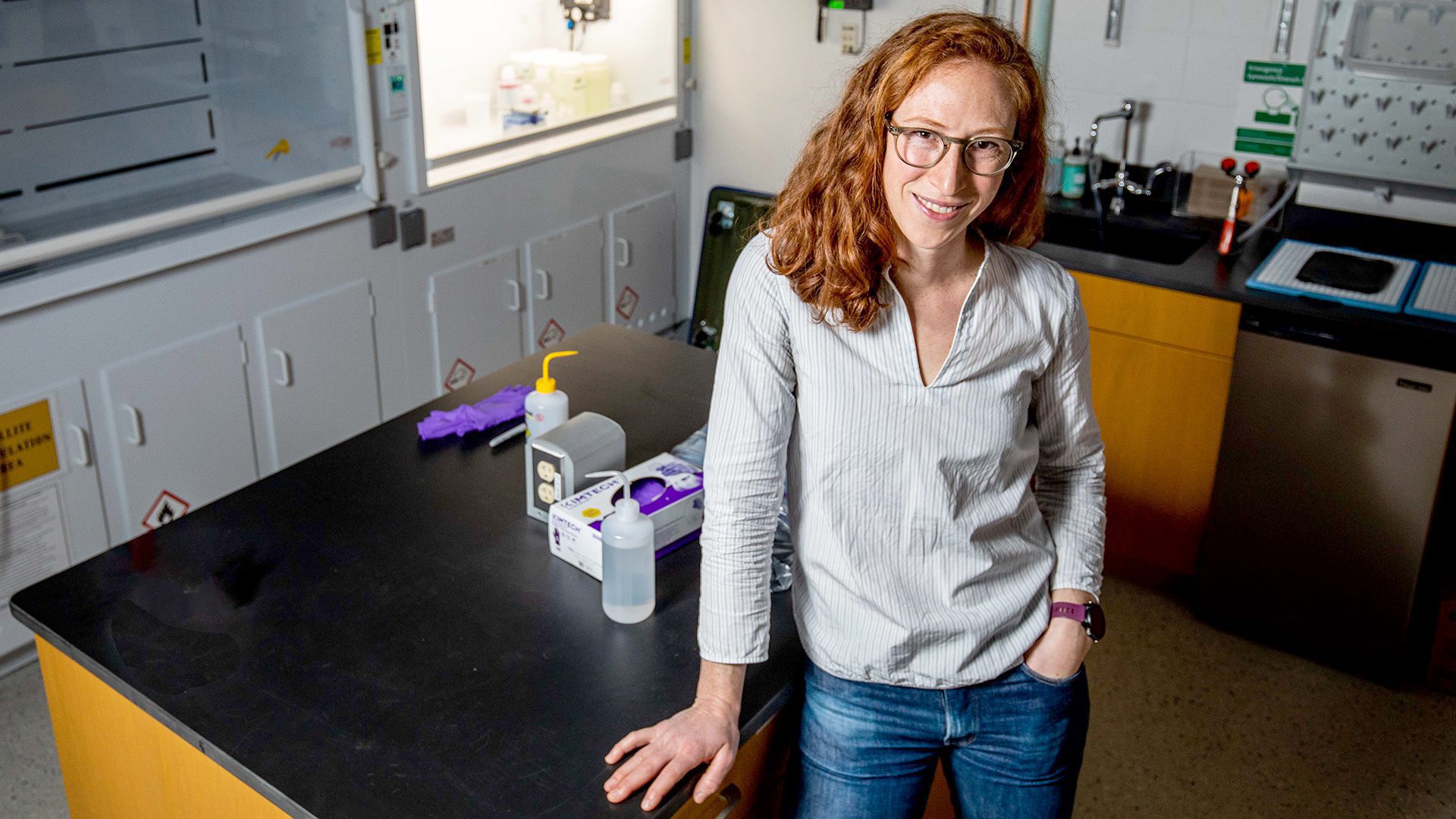

Back in the lab at WHOI, McKeon points to a storm deposit in one of the cores. During an intense storm, high energy waves can carry sediment particles much larger than would normally be transported into the sheltered bays. McKeon can identify deposits associated with extreme storms that washed sediments into the bays many hundreds or even thousands of years ago. (Photos by Daniel Hentz, © Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

Computed Tomography (CT) data from the new scanner at WHOI reveals one of the dense storm event beds (light layer) deposited more than 1500 years ago within the sediments of Unalaska. (Image courtesy of Kelly McKeon, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

“In the Aleutians, the storms are more frequent and more severe than in recent memory,” said Piama Oleyer. “There’s a sad lack of scientific study in the area, yet it’s so desperately needed. I’m hopeful that the outcome of this research is being able to connect the past to the current day somehow.” (Photo by Sarah Betcher, Farthest North Films)

MEET THE AUTHOR Evan Lubofsky

Evan Lubofsky is a science writer and editor at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. After studying journalism at UMass Amherst, he began writing about sensor and...

Read moreRelated Articles

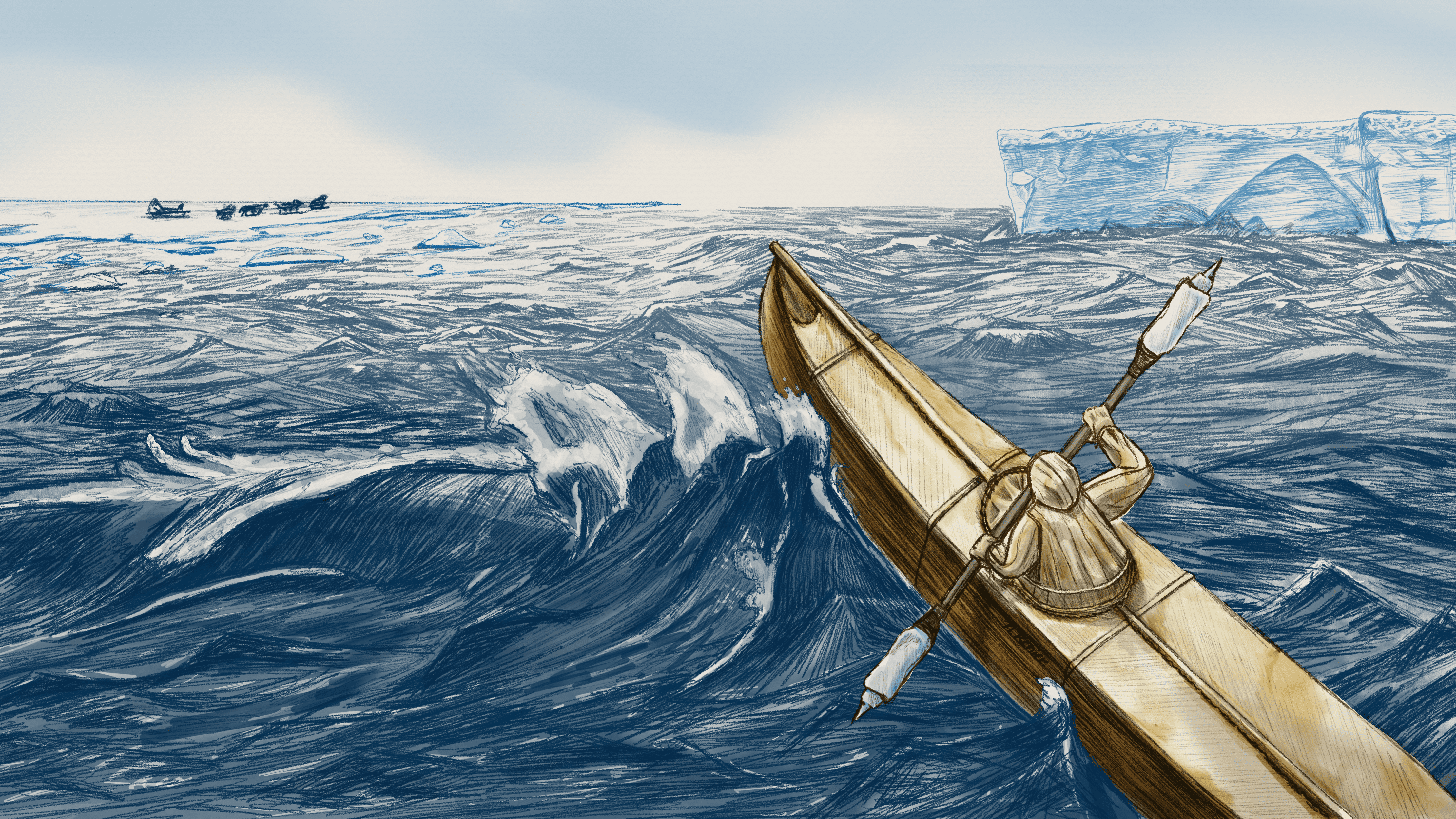

If ancient Beringians got to the Americas by boat, it couldn’t have been easy

Sophie Hines discusses the paleo-research power of fossil corals

Scientists mine ancient dust from the ocean’s loneliest spot