Noah’s Not-so-big Flood

New evidence rebuts controversial theory of Black Sea deluge

Estimated reading time: 5 minutes

This article printed in Oceanus September 2009

This article printed in Oceanus September 2009

A long time ago, whether your time frame is biblical or geological, the Black Sea was a large freshwater Black “Lake.” It was cut off from the Mediterranean Sea by a high piece of land that dammed the entry of salty seawater through the narrow connecting Bosphorus valley.

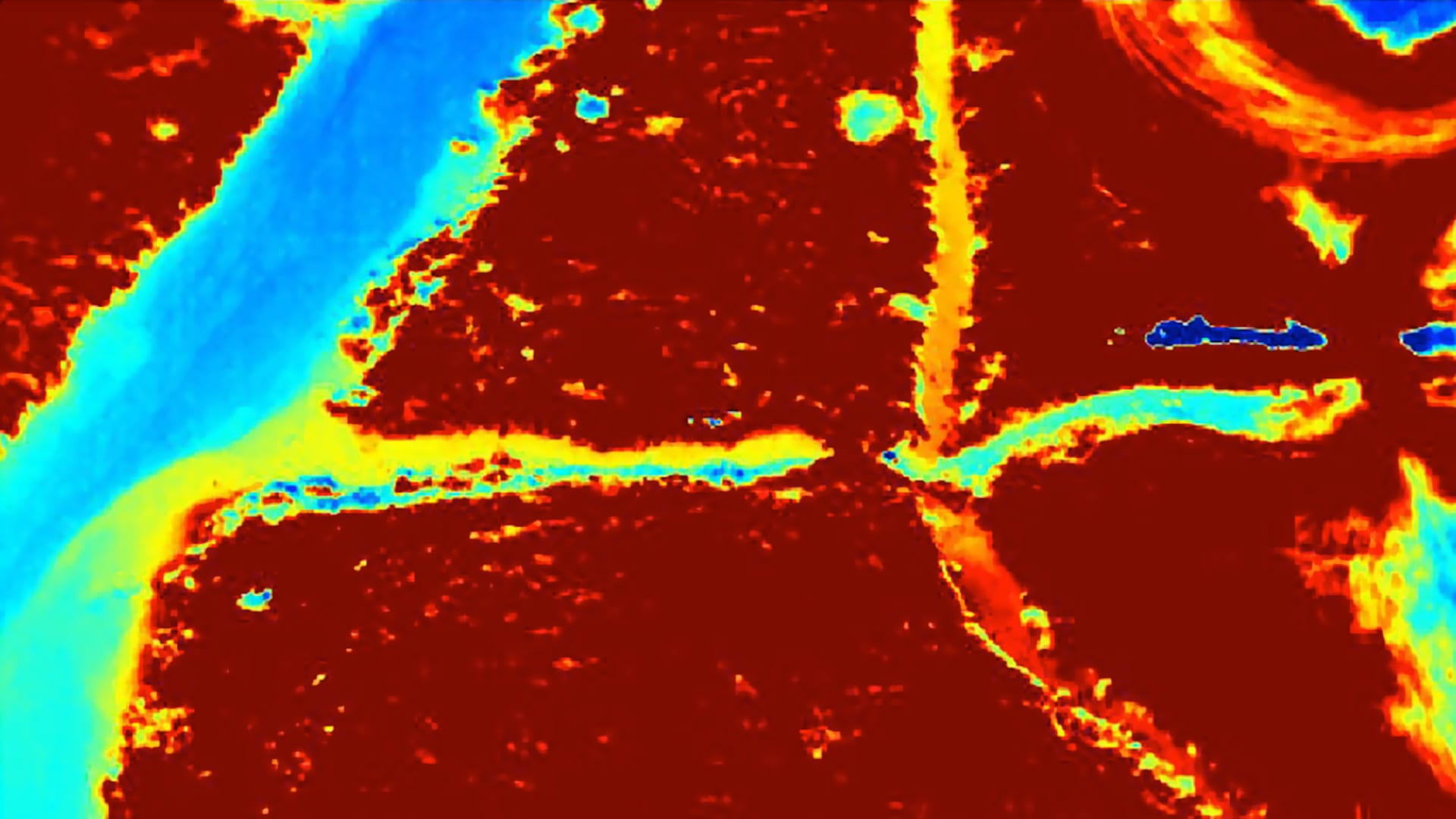

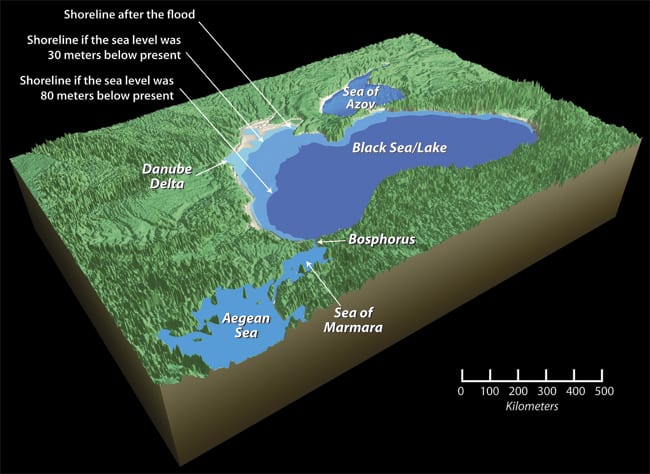

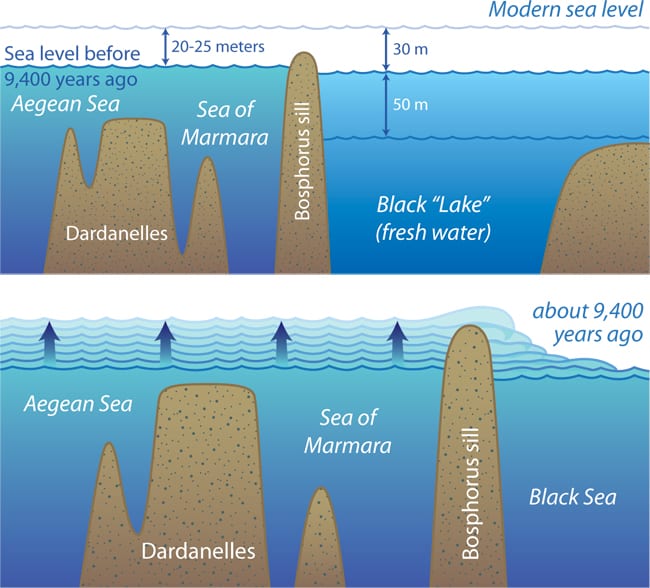

A provocative theory proposed in 1997 that water levels in “Black Lake” were 80 meters lower than today. When the Aegean and Black Seas were reconnected 9,400 years ago, the resulting would have drowned about 70,000 square kilometers. New evidence indicates that the lake’s water level was only 30 meters lower than today, and so the flood inundated only about 2,000 square kilometers. (Illustration by Jack Cook, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

When Earth’s last ice age waned, water frozen into vast ice sheets melted and returned to the ocean, elevating sea levels. About 9,400 years ago, Mediterranean waters rose above the dam, reconnecting the two seas. They surged over the now submerged Bosphorus Sill with the force of 200 Niagara Falls, according to a controversial theory proposed in 1997 by Columbia University marine geologists Bill Ryan and Walter Pitman. The resulting deluge, they speculated, could have wiped out early human settlements around the lake’s perimeter and inspired the Noah’s Ark story in the Bible, the Sumerian epic of Gilgamesh, and catastrophic flood myths among other peoples.

The story behind the stories sparked a best-selling book, considerable popular interest, and a lot of subsequent research to support or refute the theory.

Now, a new study in the January 2009 issue of Quaternary Science Reviews suggests that if the flood occurred at all, it was much smaller—hardly of biblical proportions. Liviu Giosan of Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) and Florin Filip and Stefan Constantinescu of the University of Bucharest found evidence that Black Lake/Sea water levels rose only 5 to 10 meters around 9,400 years ago, not 50 to 60 meters as Ryan and his colleagues proposed. The flood would have drowned only about 2,000 square kilometers of land (about half of Rhode Island), rather than 70,000 square kilometers (more than the entire state of West Virginia).

Top: When sea levels were lower 10,000 years ago, the Black Sea was a large freshwater Black Lake. It was dammed off from the salty Mediterranean Sea by the then high-and-dry Bosphorus Sill. Some say the water level in Black Lake was 80 meters lower than it is today, but new research claims it was only 30 meters lower.

Bottom: Why is that important? Because as the ice age waned and sea levels rose, water overtopped the Bosphorus Sill into Black Lake. A controversial theory says this might be the source of the Noah's flood story, but a new study claims that the Black Sea rose only about 5 to 10 meters, not a more catastrophic 50 to 60 meters. (Illustration by Jack Cook, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

A core through the Danube delta

Fueling the debate is the difficulty of finding reliable ways to reconstruct “Black Lake’s” water level before the flood. Investigating seafloor features, Ryan and Pitman inferred former shorelines or beach dunes, now drowned, and estimated that Black Lake was at least 80 meters lower than the Black Sea today.

But sand deposits are molded and eroded by underwater currents and can be misleadingly interpreted as dunes or beaches, and so they are less than reliable indicators of past sea levels, Giosan and colleagues said. Instead, they went to the Danube River, which empties into the Black Sea and forms an immense, flat, stable sedimentary delta. It’s like a big tabletop that forms right where land meets water and doesn’t easily move up or down. As such, it makes an excellent sea-level marker.

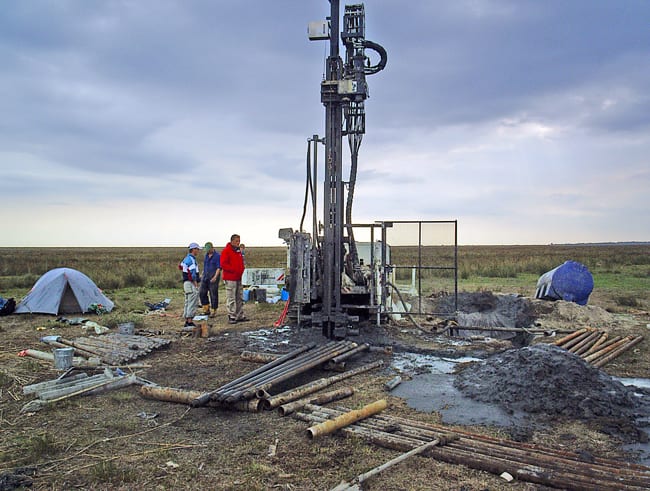

WHOI geologist Liviu Giosan at work on a core in WHOI's McLean lab. Giosan and his colleagues used cores from the delta of the Danube River, which empties into the Black Sea, to reconstruct sea level for the Black Sea and determine if it was catastrophically flooded around 9,400 years ago. Their work showed that flood occurred at all, it was much smaller than previously proposed by other researchers. (Tom Kleindinst, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

In 2007, Giosan and his colleagues drilled a 42-meter-deep core through sediments that have piled up since the early Danube delta began forming before 10,000 years ago. At the base of the modern Danube delta, they found deep delta sediments formed in fresh water, subsequently overlaid by fine sediments formed in seawater.

Was the drowning of the first delta the result of seawater overflowing the Bosphorus sill and surging up the beach? To figure out when sediments are deposited, whether on the seafloor, lakes or on land, scientists use radiocarbon dating of organic materials including fossil shells of clams or snails found in the layer. But that can sometimes be misleading, because waves can erode sediments on the seabed, heave up older shells, and redeposit them in “younger” sediments.

A new approach

To reduce the uncertainties, Giosan and his team used an approach that had not been used before in the Black Sea. They dated only bivalve shells whose halves were still attached to each other, as they are when the animals are alive. The shells are held together by an organic substance. It degrades quickly, and the shells separate when the animal dies. Still-attached shells indicate that the animals died in the layer at the time it was created and were not subsequently moved by waves.

Combining the more precise dating technique with a more reliable sea-level marker, the researchers could be confident and conclude that the “Black Lake” water level at the time of the flood was around 30—not 80—meters lower than present, and the flood raised the level by only 5 to 10—not 50 to 60—meters.

A more modest flood “still could have put an area of 2,000 square kilometers of prime agricultural land in the Danube delta under water, which has important implications for the archaeology and anthropology of Europe,” Giosan said. But was it enough to prompt an ark?

The research was funded by the WHOI Coastal Ocean Institute, the U.S. National Science Foundation, and the Romanian National Science Foundation.