Estimated reading time: 3 minutes

This article printed in Oceanus Summer 2025

This article printed in Oceanus Summer 2025

Nearly every spring and summer since 2010, giant blooms of seaweed have developed in the central Atlantic Ocean. Patches of the floating brown plant—known as Sargassum—have stretched from the west coast of Africa to the Caribbean and Gulf of America in what is known as the Great Atlantic Sargassum Belt. Scientists tracking the blooms in this part of the North Atlantic say the growth and breadth is unprecedented, begging the question—why is this happening?

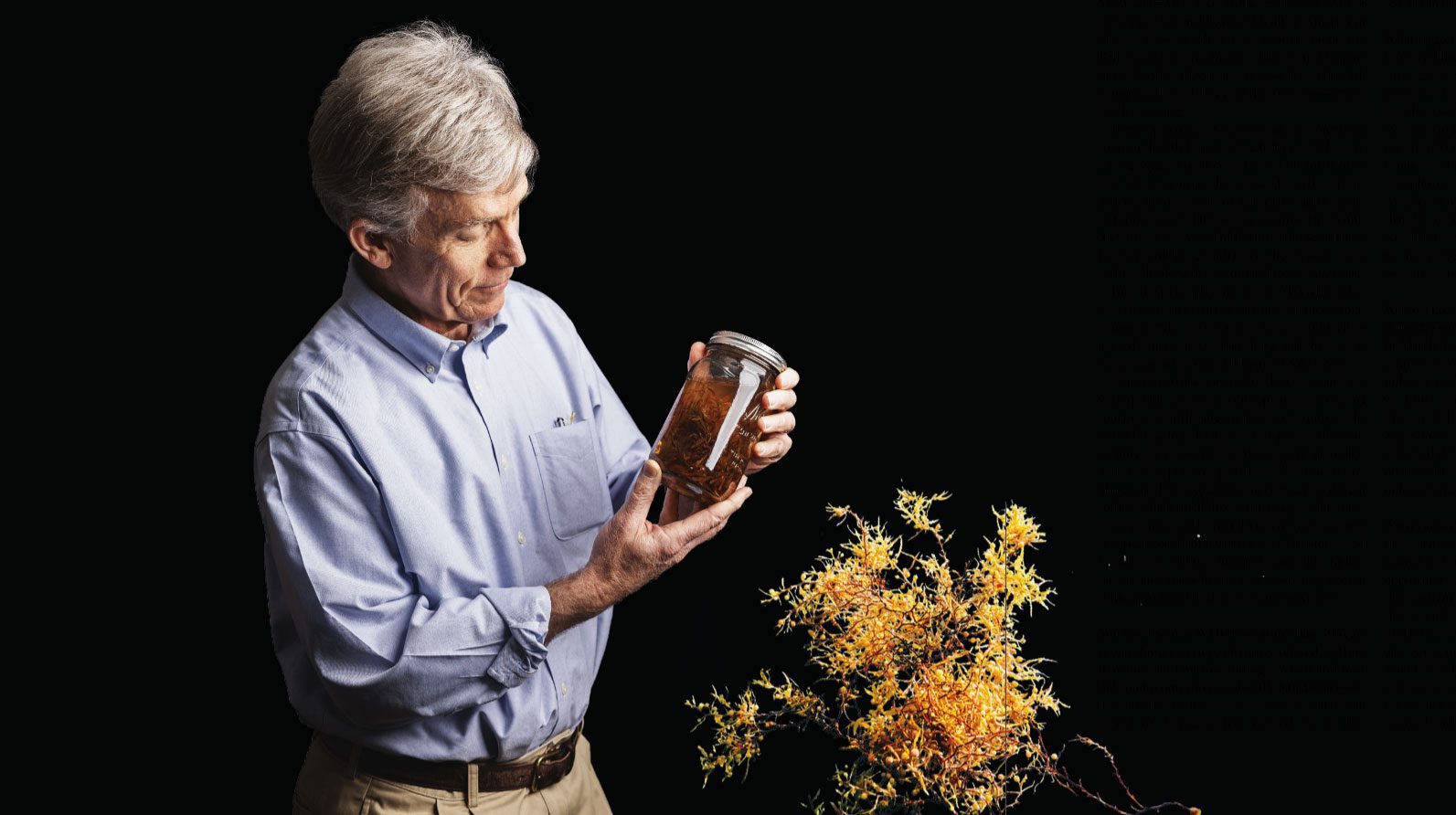

In the open ocean, Sargassum patches contribute to ocean health by providing habitat and by producing oxygen via photosynthesis. Fishermen know that Sargassum means life, a place for crab, shrimp, and juvenile fish species to hide and for adult species to forage, said WHOI senior scientist Dr. Dennis McGillicuddy. As a child, while fishing offshore Florida with his grandfather, they would chase mahi-mahi along the sea surface lines of Sargassum.

But despite playing what McGillicuddy describes as an essential role in a balanced environment, “like many other things, too much of a good thing can be a bad thing, and that’s what we’ve seen in the recent blooms of Sargassum.”

Tons of rotting seaweed on beaches can have widespread economic consequences, deterring tourists and inflicting on local communities the cost of ongoing cleanup and disposal. Also concerning are the related cardiovascular, neurological, and respiratory problems. When it decays along coastlines, Sargassum emits the gas hydrogen sulfide, which smells like rotting eggs and irritates the eyes, nose, and throat. In recent years, doctors reported more than 11,000 cases in Martinique and Guadeloupe of breathing problems, skin rashes, nausea, and headaches from exposure to hydrogen sulfide produced by decomposing Sargassum.

You have been at WHOI for more than 30 years researching a variety of topics related to fluid dynamics and marine biology. When and how did you become interested in the Sargassum issue?

Friends of WHOI with homes on the Caribbean island of Antigua first alerted me to this problem. Since 2010, Antigua’s shorelines have been inundated with Sargassum, so they asked us what was going on. I realized that it wasn’t just a problem in Antigua; this was part of a basin-scale bloom of macroalgae. In fact, it is perhaps the most conspicuous bloom of marine macroalgae ever observed.

What triggers these blooms?

From satellite and collected data from ships taken since 2010, we can see biomass continuing to grow over time. There is year-to-year variability, but the problem seems to be getting worse, and we are trying to understand why. One hypothesis is that it relates to nutrients in the marine environment. Our data shows that the nitrogen and phosphorus content of the seaweed in the Great Atlantic Sargassum Belt is significantly higher than the content found in more traditional habitats, like the Sargasso Sea around Bermuda. Now we are trying to understand where the nutrients come from to sustain these blooms.

Where have you observed Sargassum blooms through your field research?

In March, I was on an NOAA ship servicing an array of moorings along a north-south line, 200 miles west of Africa. That cut right through what we think may be the initiation zone for these blooms. I’ll never forget it; we started seeing Sargassum at about ten and a half degrees north, and we did not get out of the belt until 30 miles north of the equator. We witnessed 600 nautical miles of Sargassum.

What can we do about this issue?

If it turns out that the sources of nutrients are related to human activities, then there may be an opportunity to mitigate. And if it turns out that the nutrient sources are natural, then we hope that scientific understanding will provide some predictive capability to develop coping strategies. For example, seasonal forecasts for Sargassum would be helpful for coastal ecosystem managers and businesses to plan in advance for inundation events and perhaps find alternative uses for the seaweed, such as fertilizer.