One researcher, 15,000 whistles: Inside the effort to decode dolphin communications

By Evan Lubofsky | December 9, 2025

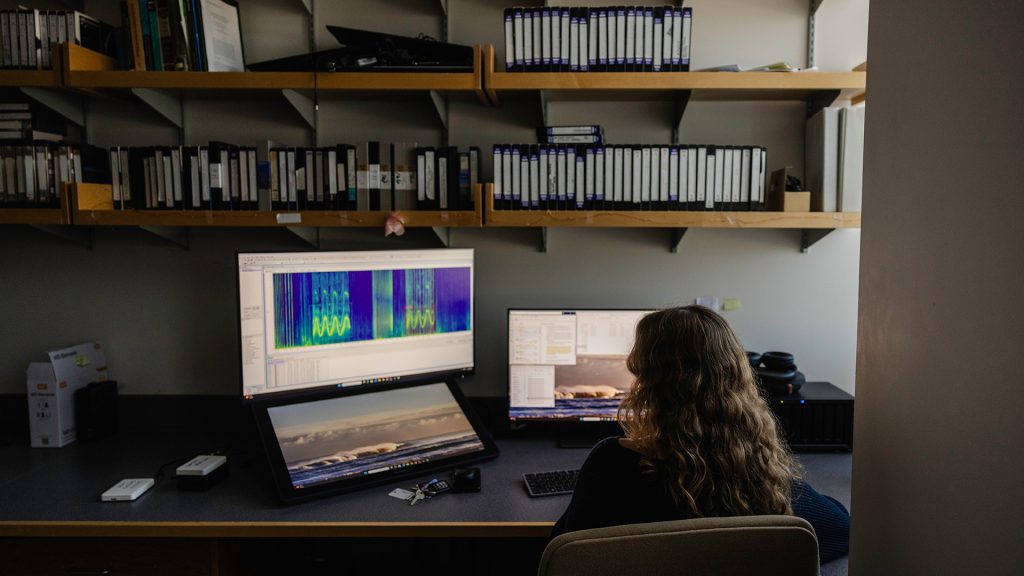

Kate Fligstein sits at her desk beneath a wall of long wooden shelves filled end to end with VHS tapes. They’re filled mostly with archival audio tracks from decades of bottlenose dolphin studies conducted by her supervisor, Laela Sayigh, a WHOI biologist and one of the world’s leading dolphin communication experts.

Fligstein, a research assistant in the Sayigh Lab, stares at her monitor as a graph comes into view. It’s a spectrogram—the fancy term for an audio file presented in visual form—of a dolphin whistle. It was produced by one of 170 wild bottlenose dolphins living year-round in Florida’s Sarasota Bay, and recorded using underwater microphones known as hydrophones, which are temporarily affixed to the animals with suction cups.

This particular whistle has a series of peaks and troughs like a financial chart. As Fligstein studies its waveforms on her screen, she cross-references field notes taken when the animal was present to identify it. Then, she checks that individual’s historical files to see if this recent whistle matches up with previous ones the dolphin has made.

“Any file I work on requires me to reference at least three components,” says Fligstein. “There’s the sound analysis program displaying the audio file; the metadata spreadsheet, where I track progress for dozens of files within a given year; and field notes, which provide me with information that is not discernible from the audio file alone.”

In this case, the new whistle is a match with previous ones made by the animal, so Fligstein marks it as a signature whistle—a unique call that functions like a name and allows a dolphin to communicate his or her identity. Sayigh and other researchers have been decoding these distinctive signature sounds, which often sound like birds chirping, for years and understand them reasonably well.

But it’s the subset of whistles that Fligstein classifies as non-signature—those beyond a dolphin’s own unique signature—that Sayigh is currently more interested in. These vocalizations have not been well studied, so little is known about what dolphins are communicating when they eek out a non-signature whistle.

“We only recently discovered that there are numerous shared, stereotyped non-signature whistles that can be produced by many different individuals in the population,” says Sayigh. “We are currently carrying out playback studies to try to determine what these whistles mean to the dolphins, and whether they might possibly function in a way similar to our own words.”

Sayigh has a healthy data set to draw on; Fligstein has audited and classified around 15,000 dolphin whistles in just the past 5 months, more than a third of which she’s tagged as non-signature. And, there’s funding from a portion of a $100,000 prize Sayigh and her colleagues at the Brookfield Zoo Chicago’s Sarasota Dolphin Research Program won for identifying the first evidence of possible language-like communication in dolphins.

“The Coller-Dolittle prize, along with ongoing support from the Avatar Alliance Foundation, has enabled us to expand our field playback experiments to study the functions of non-signature whistles,” says Sayigh. “We need a lot of data from animals of different ages and sexes, who are engaged in a variety of activities, to understand how these whistles function.”

Despite the importance of accurately classifying dolphin whistles, Fligstein is currently the only person auditing them and there’s far more data than one person can process. And doing it manually can be a very time-consuming: complex files with multiple whistles can take up to a week to classify. Sayigh sees a clear role for AI to help. She and her team are currently working with colleagues at Aarhus University in Denmark to develop AI methods that could help automate the classification process and process larger datasets.

“Once this system is up and running, we are hoping to be able to use it to help us classify non-signature whistles into stereotyped categories,” she says. “This would enable us to expand to larger datasets, for example we could detect non-signature whistles in data collected from an entire network of hydrophones throughout the Sarasota study area.”

But for now, Fligstein will continue auditing the whistles, one file at a time. Despite the labor-intensive nature of the work, she loves the process and being part of the broader effort to understand what these animals are saying.

“Communication is so fundamental to being a human, to being a living thing,” says Fligstein. “Information is constantly being communicated to us, from your dog barking at you to play, to the wind indicating a storm is coming. Many of these signals – like non-signature dolphin whistles – we can’t yet understand, but I find it fulfilling and a privilege to be part of the work to unravel these clues.”

Fligstein scans through recordings of dolphin whistles in WHOI's Marine Research Facility. (Photo by Daniel Hentz, © Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)