Busting myths about HABs

WHOI researchers give you the facts about toxic algal blooms

This article printed in Oceanus Summer 2025

This article printed in Oceanus Summer 2025

Estimated reading time: 4 minutes

Harmful algal blooms (HABs) can pose a threat to people, pets, and livestock, as well as aquatic and marine life. WHOI researchers in the Anderson and Brosnahan Labs are investigating what drives HABs; their efforts to track blooms are leading to innovative new ways to relay real-time warnings to communities to prevent illness and death from HAB toxins. Researchers Don Anderson, Mindy Richlen, and Evie Fachon weigh in on some common misconceptions about HABs and human health.

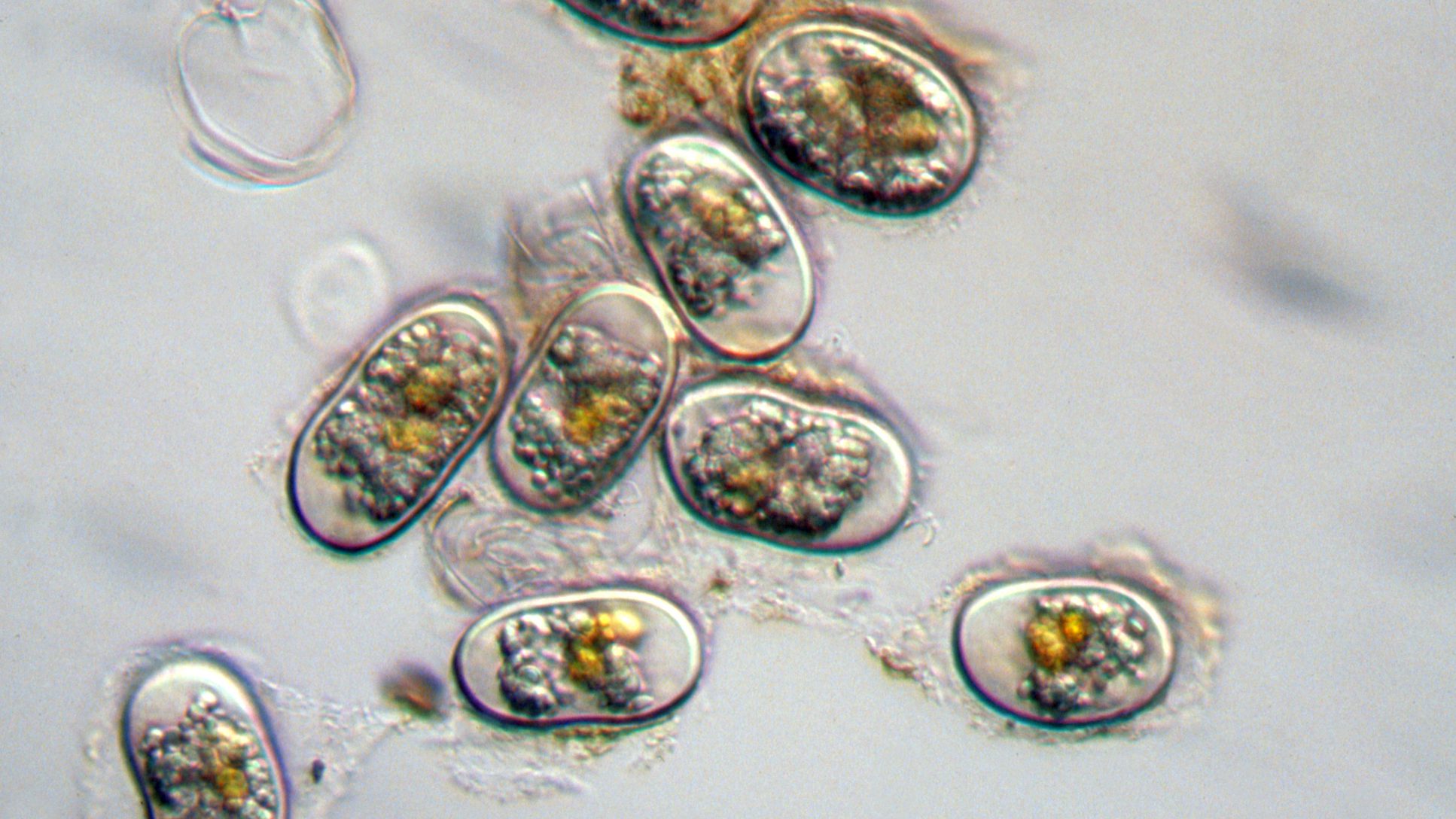

Harmful algal bloom (HAB) cells shown under a microscope. (Photo by Don Anderson, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

Myth 1

HABs always change the color of the water.

HABs used to be known as “red tides,” and the term is still used in some areas today, particularly those where large, visible blooms regularly occur. Algal blooms vary in size and duration, and truly massive events can be seen from space. The concentration of single-celled algae in the water column affects water clarity and color—millions of cells reflect light differently than clear water does.

But just because water looks clear doesn’t mean it’s safe.

“Some HABs are dangerous at very low cell concentrations,” Anderson said. It all comes down to the species of algae growing in the water. Some are highly toxic, making the water unsafe even when it looks clear, and eating shellfish from these waters can be dangerous.

“Animals like clams retain and accumulate the toxin as they feed, without any real harm to the shellfish themselves because they filter so much water,” Anderson noted. But “consuming one or two shellfish can be lethal to humans in rare cases.”

Myth 2

You can stay safe from toxins if you cook, freeze, or can seafood.

This myth likely arises from the practice of freezing, canning, and cooking to preserve meat and make it safe to eat. Heat during cooking denatures proteins, which changes their shape, rendering pathogens like bacteria harmless. But toxins produced by HABs are not proteins, so they’re not significantly affected by cooking, freezing, or canning processes.

“Heating may slightly reduce toxicity,” Anderson said, “but most HAB toxins are heat and acid stable and do not break down significantly when exposed to typical cooking temperatures and conditions.”

Evie Fachon arranges Alexandrium cultures in the incubator at WHOI’s Anderson Lab. (Photo by Daniel Hentz, © Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

Myth 3

You can build up a tolerance to HAB toxins over time.

When exposed to foreign cells and proteins, the immune system learns to recognize and respond to the invaders. However, since HAB toxins are not proteins, they’re unable to stimulate a strong immune response. In fact, long-term exposure to small amounts of these toxins can have the opposite effect.

“With one toxin family called the ciguatoxins, responsible for ciguatera fish poisoning, you become more susceptible over time,” Richlen said. “That may be because the body stores the toxins in fat. As someone is exposed to ciguatoxins through their diet, their body’s capacity to deal with it diminishes. In effect, one becomes sensitized over time.”

Anderson added, “Fortunately, most other HAB toxins do not have this characteristic, but in general, most people do not develop immunity or tolerance from toxin exposure.”

Myth 4

To be safe from HABs, you should eat shellfish only in months that contain the letter ‘r.’

This myth has a bit of truth to it—at least in northern temperate regions. That’s because the only months without an “r” are in spring and summer, which coincide with most algal blooms. The saying goes back to at least the 1500s, having originated, apparently, in Europe.

Although this “rule” may have been a good guide in the past, that’s no longer the case.

“Toxic blooms can happen any time of year, so you can’t rely on that,” Fachon said. That’s especially true for tropical and subtropical regions, where winter blooms are common. “Even in temperate regions, blooms now extend into months when they didn’t used to occur, as regional waters warm with climate change,” she added.

Myth 5

HABs pose a threat only to people.

Humans, seabirds, and marine mammals are all at high risk of poisoning by HAB toxins. In each case, “they have picked up that toxin through the food web,” Anderson said. In truth, HAB poisoning has caused spectacular die-offs or illnesses of marine seabirds and mammals. A 1961 event inspired Alfred Hitchcock’s movie The Birds. Seabirds in California “had domoic acid poisoning,” Fachon said. “And that was what was causing them to behave erratically.”

Some blooms don’t release toxins but still pose a danger to ecosystems. A dense layer of algae on the water’s surface shades aquatic plants, threatening the base of the aquatic food web. When that large mass of algae dies, its decomposition consumes oxygen in the water, suffocating fish and other animals.

Hundreds of dead fish from the Gulf of Mexico killed by a red tide are washed up on Siesta Beach at Sarasota, Florida, USA. (Photo by Michele and Tom Grimm / Alamy Stock Photo)