As the ocean warms, a science writer looks for coral solutions

Scientist-turned-author Juli Berwald highlights conservation projects to restore coral reefs

Estimated reading time: 3 minutes

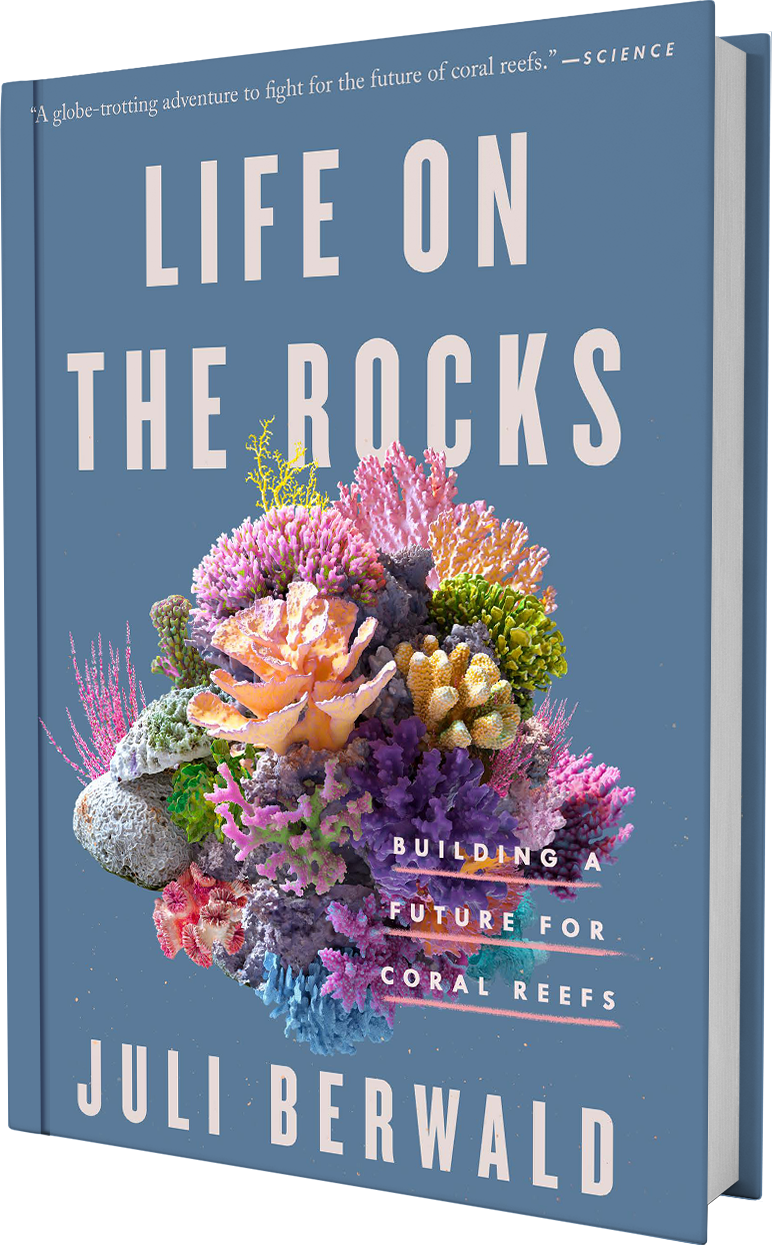

Juli Berwald felt lonely and adrift on her junior study abroad, but when she saw a poster for a weeklong course, she grabbed a tear-off tab. As a math major, Berwald knew nothing about marine ecology or diving, but when she plunged into the Red Sea, she was captivated by colorful and complex gardens teeming with animal life, and their outsized role in the health of marine ecosystems.

Berwald returned to Amherst to finish college, and immediately dove into self-directed coral studies, intent on becoming a marine biologist. But without the prerequisite coursework for graduate programs, she had to build her credentials from the ground up, including a move to Woods Hole for a summer job at the Marine Biological Laboratory scrubbing laboratory glassware.

As a graduate student at the University of California, Berwald finally appeared to have found her place in marine science, constructing mathematical algorithms to study the link between light and photosynthesis through satellite imagery. Despite having secured a postdoctoral position, though, she had not found her right fit with academia. Once again, Berwald pivoted to something entirely unexpected.

But what she discovered in her research was alarming: the vibrant underwater gardens of her memory were disappearing. Once densely crowded reefs were bleaching white, their symbiotic relationships with algae severed by warming waters and a rapidly changing environment. The reefs also faced threats like water quality issues, illegal fishing, bottom trawling, ship anchors, and disease.

Looking ahead to 2050, scientists warn, we could lose the animal forever. But “I didn’t want to write an obituary,” Berwald told a recent audience at a WHOI event sponsored by the Yawkey Foundation. Instead, her book asks us to envision the utterly unforeseen, weighing different strategies to make reefs more resilient.

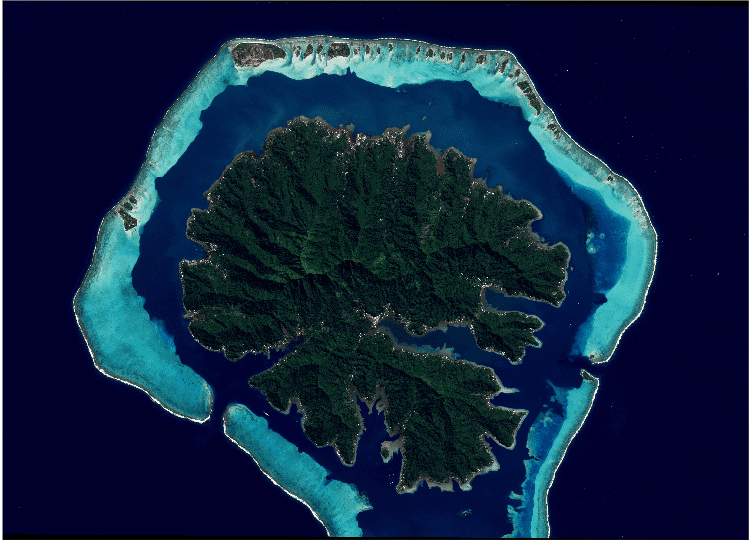

In The Coral Triangle of the Pacific Ocean, Berwald describes steel rods that are arranged on degraded reef sections. These star-shaped rebar, studded with coral fragments, have shown promise in fostering new growth and boosting biodiversity. In the lab, researchers test other innovations: mapping DNA to genetically engineer more climate-resilient coral and rearing larvae no bigger than pinheads until they are old enough to survive on the wild reef.

While each of these techniques have had varying levels of success, how to bring them from the local to the ecosystem scale persists as one of the biggest challenges. It’s a question that drives the same determination and fortitude of WHOI scientists and engineers as they develop cutting-edge technologies and protocols.

Following Berwald’s presentation, microbial ecologist Amy Apprill highlighted two innovations in WHOI’s interdisciplinary Reef Solutions group. The first was an eDNA (short for Environmental DNA) sampler that captures the genetic traces of organisms as they move through the water. In just a jar of water, researchers get a snapshot of biodiversity that helps them diagnose a reef’s health before treatment, so they know where to invest their time and effort.

Apprill also demonstrated RAPS, a Reef Acoustic Playback System, used by WHOI scientists Aran Mooney and Nadege Aoki. The underwater speaker broadcasts the grunts, choruses, and snaps of fish and invertebrates from healthy reefs to attract coral larvae to settle and grow into thriving colonies.

While there’s no silver bullet, Berwald reminds us that the question isn’t whether we have the necessary tools, but whether we can coordinate our best research and engineering into a global rescue mission for coral reefs.