In 2006 WIRED Magazine published an article listing “The Top 50 Best Robots Ever” (both real and fictional). Among the mechanical honorees were 2001: A Space Odyssey’s Hal 9000, R2D2, two of NASA’s Mars rovers, and a curious starship-shaped robot from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution named ABE. But who or what is an ABE?

WHOI engineer and the creator behind ABE’s design, Al Bradley makes adjustments to the vehicle before a dive to the “Lost City” hydrothermal vent field in the Atlantic. (Photo by John Hayes, © Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

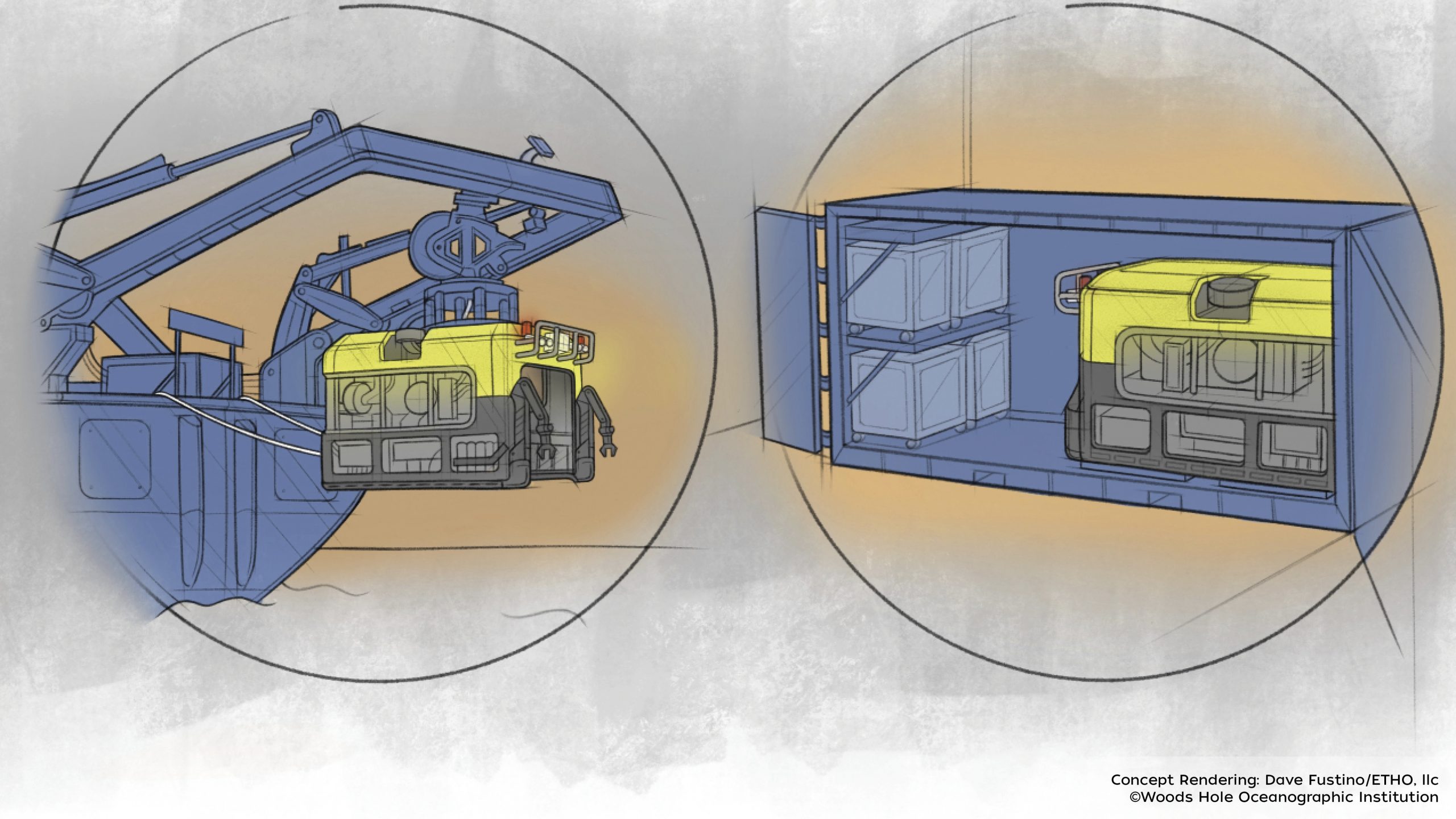

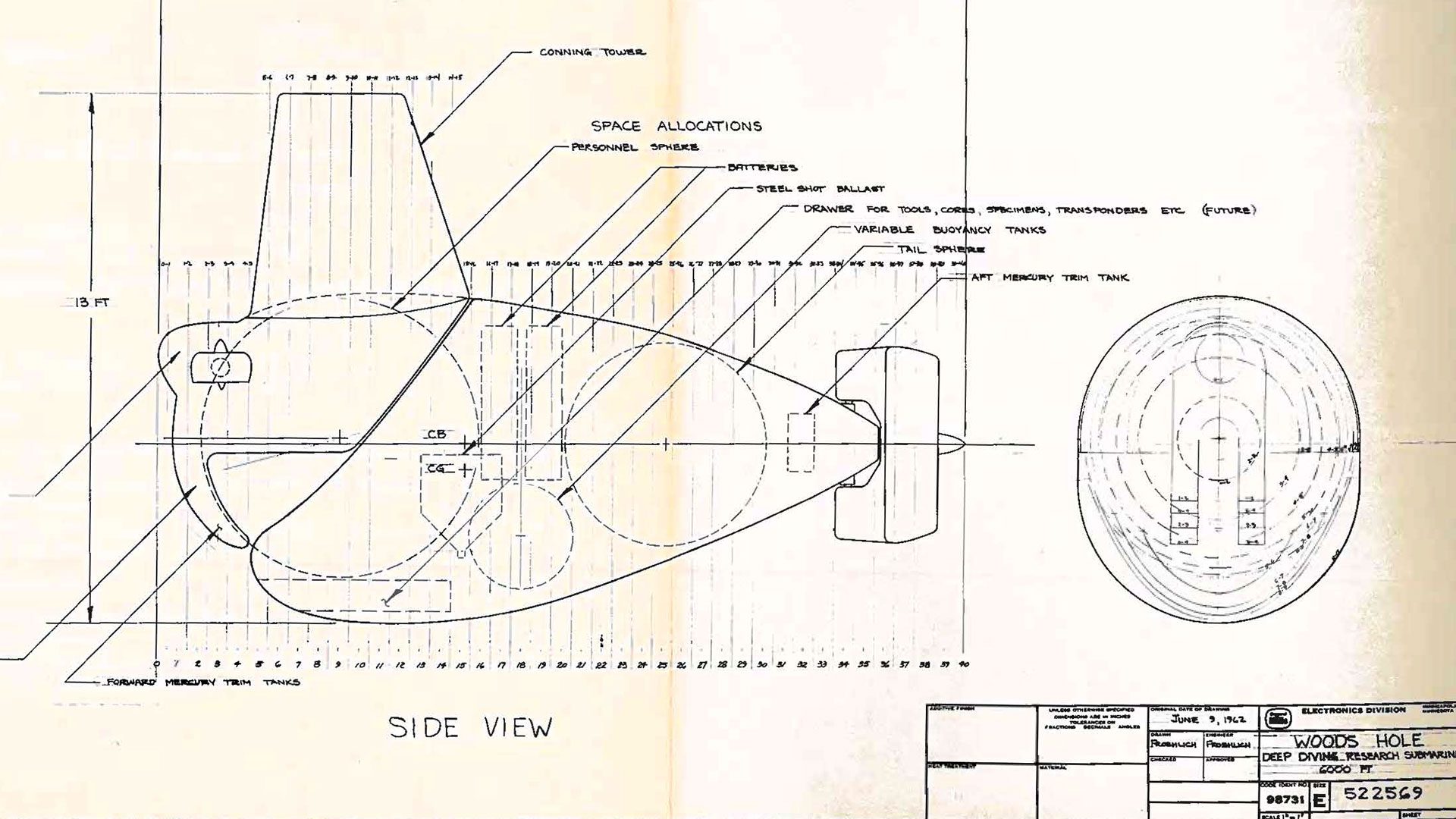

In the decades following Bob Ballard’s first discovery of hydrothermal vents in 1977, scientists scrambled to get to the seafloor to learn more. That insatiable curiosity created problems of its own. Deploying more seasoned deep-sea submersibles like HOV Alvin was costly, and pilots wanted to reserve the sub to search for new vent sites. In an effort to free up Alvin to explore new locations, then-WHOI engineer Al Bradley developed the Autonomous Benthic Explorer (ABE)—initially to gather more data about the life and chemistry of previously established vent sites. But the bot quickly became so much more than that.

Armed with bathymetric software, a pre-programmed route, and a 12-bit camera (a little more resolution than the average iPhone), ABE was able to generate large-scale maps that identified treacherous obstacles and geological wonders that would’ve otherwise been missed. This, in turn, informed Alvin’s dive plans, so scientists could be more deliberate about where they wanted to go. WHOI’s benthic explorers had suddenly gone from fumbling around in the dark to moving more intentionally under ABE’s light.

“We were like hikers with no heading,” says WHOI engineer Dana Yoerger, who programmed the vehicle and processed its data. “ABE gave us the map to find our way around.”

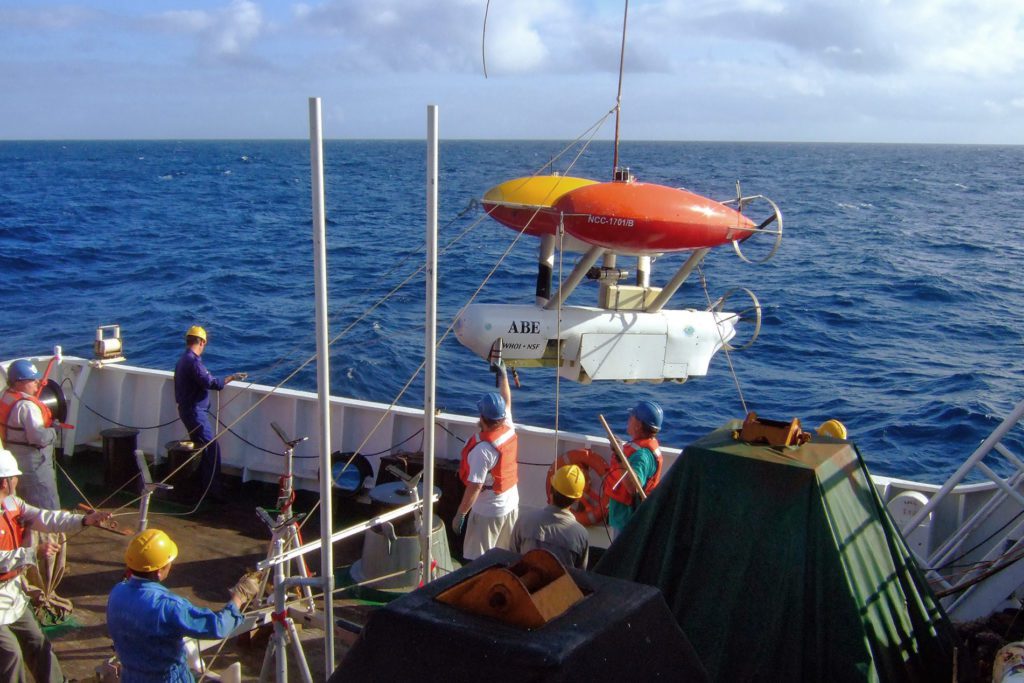

ABE’s successes quickly garnered the attention of others who wanted to use the vehicle for deep-sea research. In 1999, the vehicle made the first high-resolution maps of an underwater mountain ridge called the Southern East Pacific Rise. Six years later, ABE helped scientists make the first discovery of hydrothermal vents in the Southern Atlantic Basin and then unexplored vents in the Southwest Indian Ocean. ABE was a discovery machine, and it became clear that its autonomy was a big reason why.

“Because it didn’t get bored, ABE could do a better job of sampling than a human could,” says WHOI geochemist Chris German, one of the vehicle’s most steadfast users. “And it could do the same surveys as some of our remotely operated vehicles in a fraction of the time.”

Thanks to that efficiency, autonomous underwater vehicles, or AUVs, are now a staple of the National Deep Submergence Facility at WHOI. By 2008, interest in ABE’s capabilities helped drum up funding for another self-guided bot, hybrid vehicle Nereus. Then came hybrid vehicle Nereid Under Ice, which is still in operation, and ABE’s successor, AUV Sentry, which today has accomplished over 700 scientific dives. Vehicles became faster and more streamlined, with more accurate track lines and bigger sensor payloads. Now, it’s rare to have an Alvin dive plan that isn’t in some way informed by an autonomous scout.

“The lesson ABE taught us was that these [robots] are perfectly complementary to other vehicles,” adds Yoerger.

But as with all good things, ABE’s time came to an end when it disappeared during a mission off the coast of Chile in 2010.

ABE is brought back aboard the Chinese research vessel Da Yang Yi Hao following a mission to study hydrothermal vents along the East Pacific Rise, a deep-sea volcanic mountain range in the Pacific Ocean. (Photo by Dana Yoerger, © Woods Hole Oceaongraphic Institution)

On the surface, the robot’s “death” seemed unceremonious. Aboard the research ship that deployed it, pings on a computer screen resembling the vehicle’s location along the seafloor suddenly and quietly stopped. At depth, however, something far more violent had likely occurred. If ABE had indeed imploded as its caretakers thought, the resulting energy given off by the vehicle’s destroyed pressure casings would have been equivalent in magnitude to three sticks of dynamite. Some in the science community mourned the robot. There were even obituaries in The New York Times and the journal Nature.

Today, ABE’s legacy continues to pave the way for new vehicles that are headed to the seafloor with the shared mission of broadening humanity’s understanding of the ocean.

“ABE broke the mold,” says German. “It proved conceptually what could be done.”