How an MIT-WHOI student used Google Earth to uncover a river–coral reef connection

By Amelia Macapia | November 26, 2025

It was Megan Gillen’s first year of graduate school, a time she had imagined mapping and documenting marine landscapes from research vessels like other MIT-WHOI Joint Program students. As COVID-19 spread across the world, and international travel became restricted, fieldwork was no longer a possibility. From her apartment in Cambridge, Massachusetts, she began searching for another way to conduct research for her qualifying exams in geomorphology, the search for processes that actively changed the landscape.

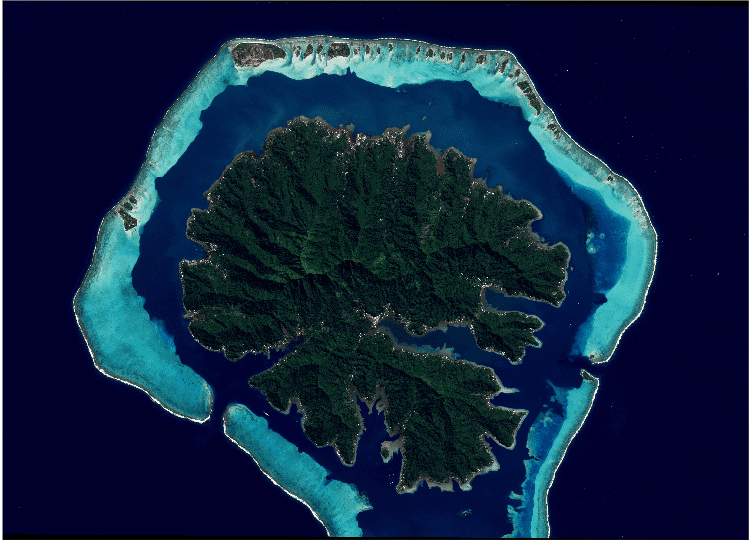

The reefs she wanted to study were thousands of miles away, so her search turned digital in search of a morphologic signature, evidence of a relationship determined through the shape and size of the land. She and Joint Program Professor Taylor Perron, masked and six feet apart, began a careful survey across Google Earth, panning over continents and coastlines. They were hovering above a chain of volcanic islands and fringing and barrier reefs of coral rings known as atolls in the Southern Pacific Ocean: the Society Islands. The scatter of cyan rings encircling the forested islands flashed across the screen, so bright they were piercing.

Perron pointed out something interesting: dark blue channels slicing cleanly through some of the atolls, otherwise identical to coral that grew in a closed circle. These openings, or reef passes, are so deep and wide that ships can navigate through them. From Gillen’s screen, it looked like the reef passes lined up with the flooded mouths of valleys, embayments where large island rivers deposit into the sea. Gillen began to wonder if it was rivers that had shaped those passes.

Researchers have been analyzing island evolution and atoll formation since Darwin’s expedition on the HMS Beagle. The only literature Gillen could find on reef passes was from the 1940s, but those researchers merely observed the coincidence of reef passes and alignment with embayments and made no further study of it. For Gillen, it wasn’t enough to cite an assumption, she wanted to identify and measure the precise forces that opened those striking gaps in coral rings.

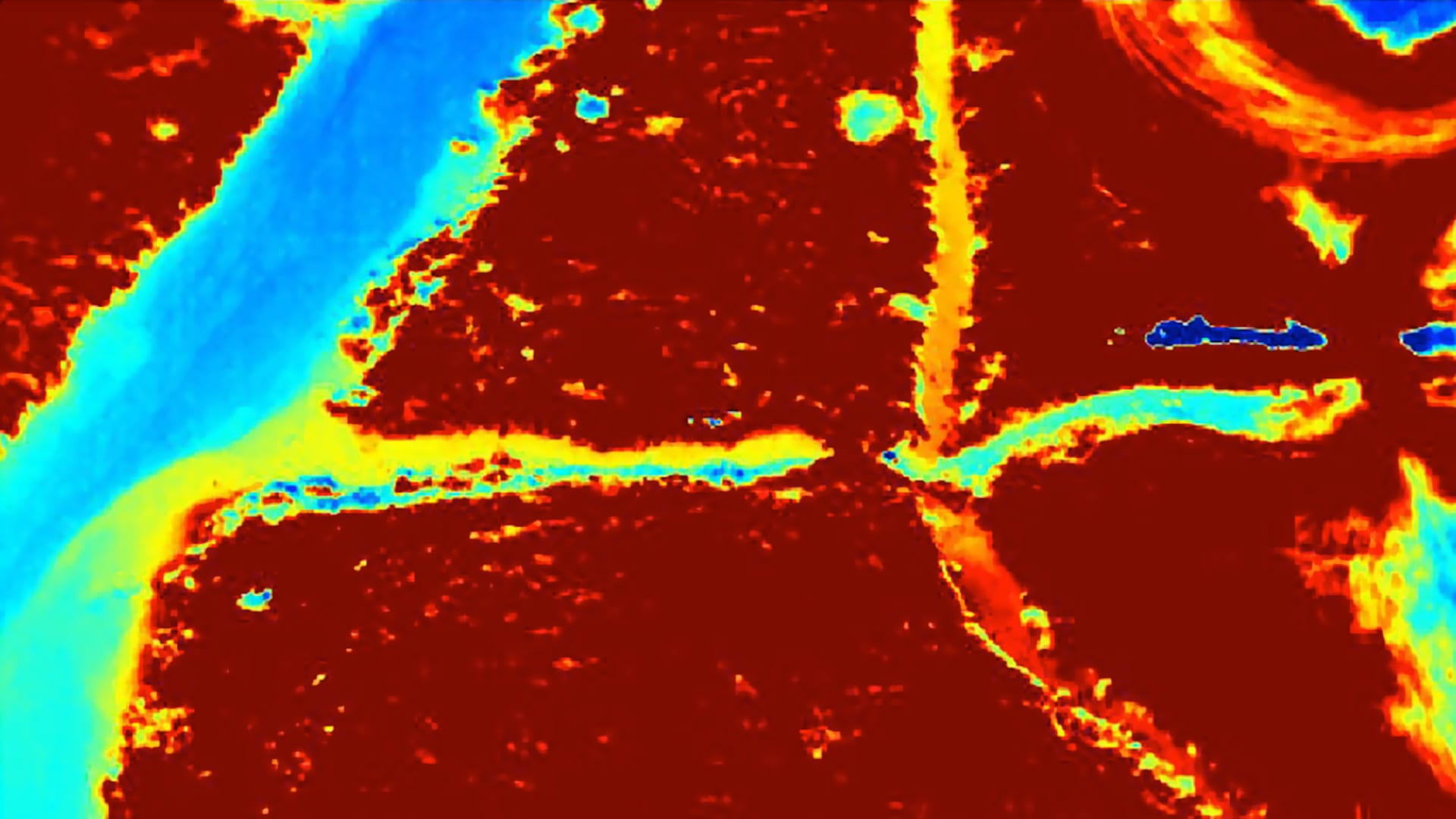

She, Perron, and the study’s other lead author, WHOI associate scientist Andrew Ashton, began investigating possible reef pass mechanisms over sea level cycles spanning thousands of years. But islands are challenging to study from global pilot imagery, they can be so small that from the sky they seem no bigger than the size of a pixel. To help, the team used some of Earth’s highest resolution topographical mapping, taken by two radar antennas on a 1999 NASA radar space shuttle mission.

Gillen spent uncountable hours in GIS, mapping out the elevations of each island. As though unwrapping each island along its coast, she identified each of their watersheds and drainage basins to figure out how much of the island’s water sources were draining to the reef. She spent so much time staring at images of these places that Perron joked she could “identify any island based on shape and size alone.”

The researchers found a direct relationship between where the rivers drained and the breaks in the coral rings. They envision two forces shaping the reef passes: one when sea level is low and one when sea level is high. Reef incision occurred during ice ages when large quantities of water froze and sea levels fell. With new parts of the seafloor exposed, rivers with highly abrasive sediment could flow over or through the reef, carving it.

Thousands of years later, when ice melted and sea levels rose again, the ocean flooded those river-carved valleys. Corals grew upward and inward across the newly submerged valleys. But the valleys were filled with loose, unstable river sediments, with calmer waves than on the open reef, creating a persistent gap that the corals weren’t able to fully seal.

The findings didn’t end with sea level change. Over millions of years, the islands themselves evolved, reshaping the very reefs surrounding them. As islands age and their magmatic hotspots migrate away, they start to sink and submerge. Instead of rivers carrying material flushed out from the land, the sinking landmass forms a lagoon, at which point oceanographic processes take over, transporting coral material and other sediments that gradually accumulate to close the passes. This becomes particularly striking when comparing Tahiti, a younger island with 38 reef passes, to Bora Bora, a much more ancient one, millions of years along in its evolution, with only one.

It wasn’t until three years later that Gillen had the opportunity to do fieldwork for another research project. During a layover in Teahupo’o, a Tahitian village in the Society Islands famous for its surf conditions, Gillen stood on the shore. Instead of only a few pixels wide, the reef passes were hundreds of meters across and much farther out than she had realized.

“Being stuck inside in Boston around the wintertime during the pandemic, tracing beautiful island after beautiful island was not the easiest,” she said. By the time she’d completed the project, she had traced reef shorelines across the Society Islands, learning the curves of lagoons and the geometry of rivers intersecting reefs. From her apartment, she couldn’t experience the waves or heat on the beaches, but she could learn the patterns shaping the reefs and their place in the life cycle of islands that only distance could reveal.