Breaking down plastics together

Through a surprising and successful partnership, WHOI and Eastman scientists are reinventing what we throw away

Estimated reading time: 4 minutes

This article printed in Oceanus Winter 2025 - SPECIAL ISSUE

This article printed in Oceanus Winter 2025 - SPECIAL ISSUE

Past and present members of Collin Ward’s WHOI laboratory team gathered at Eastman’s headquarters in Kingsport, Tenn. From left: chemist Bryan James (now at Northeastern University), marine chemist Chris Reddy, biogeochemist Collin Ward, and postdoctoral investigator Yanchen Sun. (Photo by Brian Edwards, Eastman)

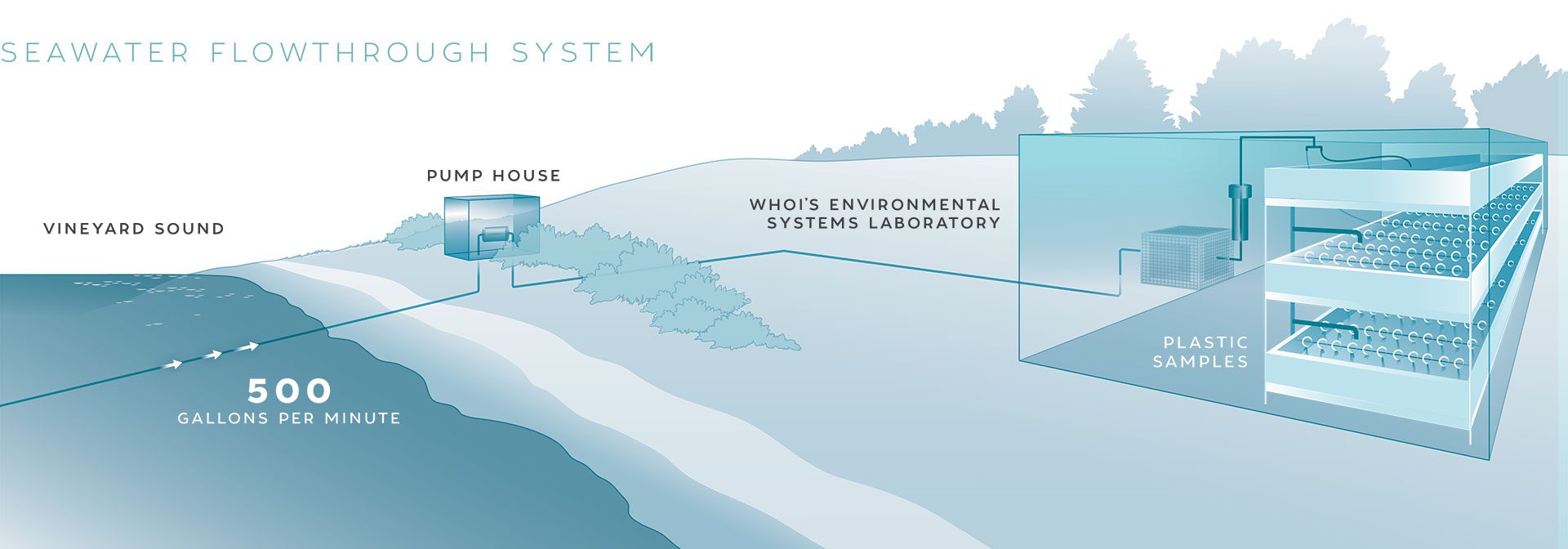

In a small building on Cape Cod, adjacent to a busy coastal bike path, seawater flows day and night through underground pipes from Vineyard Sound into a tank filled with hundreds of postage-stamp-sized plastic samples. Each sample—clipped to a wire and labeled with a colorful tag—represents a disposable plastic item that consumers may use just once: drinking straws, meat packaging trays, takeout containers.

At WHOI, biogeochemist Collin Ward studies what happens next. With the equivalent of a garbage truck’s worth of plastic entering the ocean every minute—an estimated 11 million metric tons of waste each year—Ward is racing to develop alternatives to traditional plastics that can persist in the marine environment for decades, or even centuries. His focus is on fast-degrading materials like cellulose diacetate, a chemically modified version of wood, cotton, and other plant matter.

Notably, Ward’s partner—and funder—in this work is Eastman, a major producer of plastic packaging, textiles, and fiber materials. In the face of growing environmental challenges and uncertain federal research support, Ward calls this type of partnership essential, not just for his lab, but across the scientific community.

Since 2019, when the partnership began after an initial meeting with Eastman scientists and executives at a barbecue restaurant near the company’s Tennessee headquarters, Eastman has committed $1.9 million to funding alternative plastics research at WHOI. The partnership has already produced promising results—millions of consumers have used the new materials, and, in the coming years, these alternatives could drive meaningful change. The materials studied at WHOI translate to Eastman products such as sustainable fabric for major clothing brands, compostable straws available at convenience stores, and trays for meats sold in grocery stores.

In his WHOI lab, Ward tests how quickly Eastman’s plastic samples degrade after spending weeks or months in flowing seawater while being naturally broken down by microbes.

“There’s a widespread, long-lasting stigma in the earth and ocean sciences about working with industry,” Ward said. “In many ways, this partnership helps break that stigma and encourages more folks at WHOI and elsewhere to engage in such collaborations.”

“It’s the same foaming process used to make polystyrene or Styrofoam articles, like meat trays,” Ward says. “That makes it a ‘turnkey’ replacement—no expensive new manufacturing equipment required.”

The team expected that the more porous structure of their foamed material would increase its surface area and accelerate microbial breakdown. It did. In an eight-month seawater immersion study, the foam lost 65 to 70 percent of its mass, making it the fastest-degrading plastic ever tested in a marine environment, according to Ward’s 2024 paper in the American Chemical Society journal.

Eastman also developed a prototype straw from the wood-based material. In a four-month experiment, these straws degraded faster than paper ones, which typically last about two years in seawater. Today, compostable straws made from marine-degradable material are already in use at national chains like 7-Eleven, which distributes millions of straws each year, says Jeff Carbeck, Eastman’s Vice President of Corporate Innovation.

Carbeck sees this partnership—a pairing of an environmental biogeochemist and Eastman’s materials scientists—as a model that could be replicated between other companies and academic institutions.

“It’s a true collaboration toward a common goal,” he says. “WHOI challenges us to push the limits. And we challenge them back. Behind all of this is strong academic rigor, peer-reviewed publications, and great science on both sides.”

Building a strong partnership took time and persistence. Carol Anne Clayson, a senior physical oceanographer at WHOI, reconnected in 2012 with her former Brigham Young University classmate David Golden, then a senior executive at Eastman. They began introducing their colleagues from both organizations, making multiple visits between coastal WHOI in Massachusetts and landlocked Eastman in Tennessee.

“It was frosty at first,” Clayson recalls, describing early meetings marked by “crossed arms and some suspicions about each organization’s agenda.” As trust developed, Eastman funded several smaller research projects at WHOI.

“By starting small, the team broke through the typical barriers of corporate organizational complexity and academic skepticism,” Carbeck says. “This steady process of engagement laid the groundwork for a partnership capable of driving meaningful scientific breakthroughs.”

Ward and WHOI colleague Chris Reddy, a chemist and marine pollution expert, quickly recognized the potential. After their first lunch meeting with Eastman executives in 2019—including CEO Mark Costa—Reddy called the discussion “a watershed.”

“We were taking notes on our barbecue-stained napkins,” Reddy says. “We were learning so much in that first conversation about how plastics are made—things not found in peer-reviewed literature. They were so willing to exchange ideas.”

“I need to learn from them,” Ward adds. “My background is in environmental biogeochemistry, not materials sciences and engineering,” he says. His role, he said, is to understand how organic molecules break down, what byproducts result, and how long the process takes. Meanwhile, Eastman—a 1994 spin-off of the 100-year-old Kodak company—brings decades of experience in developing and manufacturing materials at scale.

This spring, as seawater gurgled through pipes and tanks in his WHOI lab, Ward examined a sample that had been soaking for two weeks. Ward then noted that the next research frontier with Eastman will include materials in freshwater, such as lakes, streams, and other inland waterways.

“Forming this team is leading to quicker plastics solutions than if we were working in silos,” Ward says. “I guarantee that.”