Estimated reading time: 2 minutes

On a windswept winter day off the coast, kelp farmer Susan Wicks of New York-based Violet Cove Oyster Company braces herself as the boat rocks on choppy seas. Cold bites at her exposed fingers as she carefully unspools string embedded with tiny kelp seedlings and submerges it in the frigid water.

These ‘seeded strings’ must be fastened to long underwater grow lines, where the young kelp will attach and mature into full-sized blades. This process can take hours. “The cold is something we have to be vigilant about,” says Wicks. “There is the threat of hypothermia if our core temperature drops. It takes a long time to warm back up and can be dangerous.”

For decades, kelp farmers have relied on manual labor to attach seed strings to farm lines. “Seeding ropes relies on human hands, often in near-freezing conditions,” said Scott Lindell, a research specialist in marine farming at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI). “Every minute counts. If the seed string is exposed to a freezing wind chill for five to ten minutes, it can be fatal to the fragile kelp seedlings.”

Farming is hard work,” said Ben Weiss, an engineer at WHOI. “Whether you're growing vegetables on land or, in this case, kelp at sea, labor-intensive processes make it difficult for small farms to thrive.”

To address one of the kelp industry’s biggest bottlenecks, a research team led by WHOI research associate David Bailey and WHOI engineers Robin Littlefield and Ben Weiss collaborated with WHOI’s Lindell Lab to develop an automated underwater seaweed seed-string deployment device.

The autonomous underwater technology, currently being tested in Alaska and Maine, attaches seed string to submerged grow lines, minimizing handling and protecting the seeds from damaging air temperatures. By keeping the lines submerged, the device increases seed survivability and reduces the time kelp farmers spend exposed to cold, wet conditions.

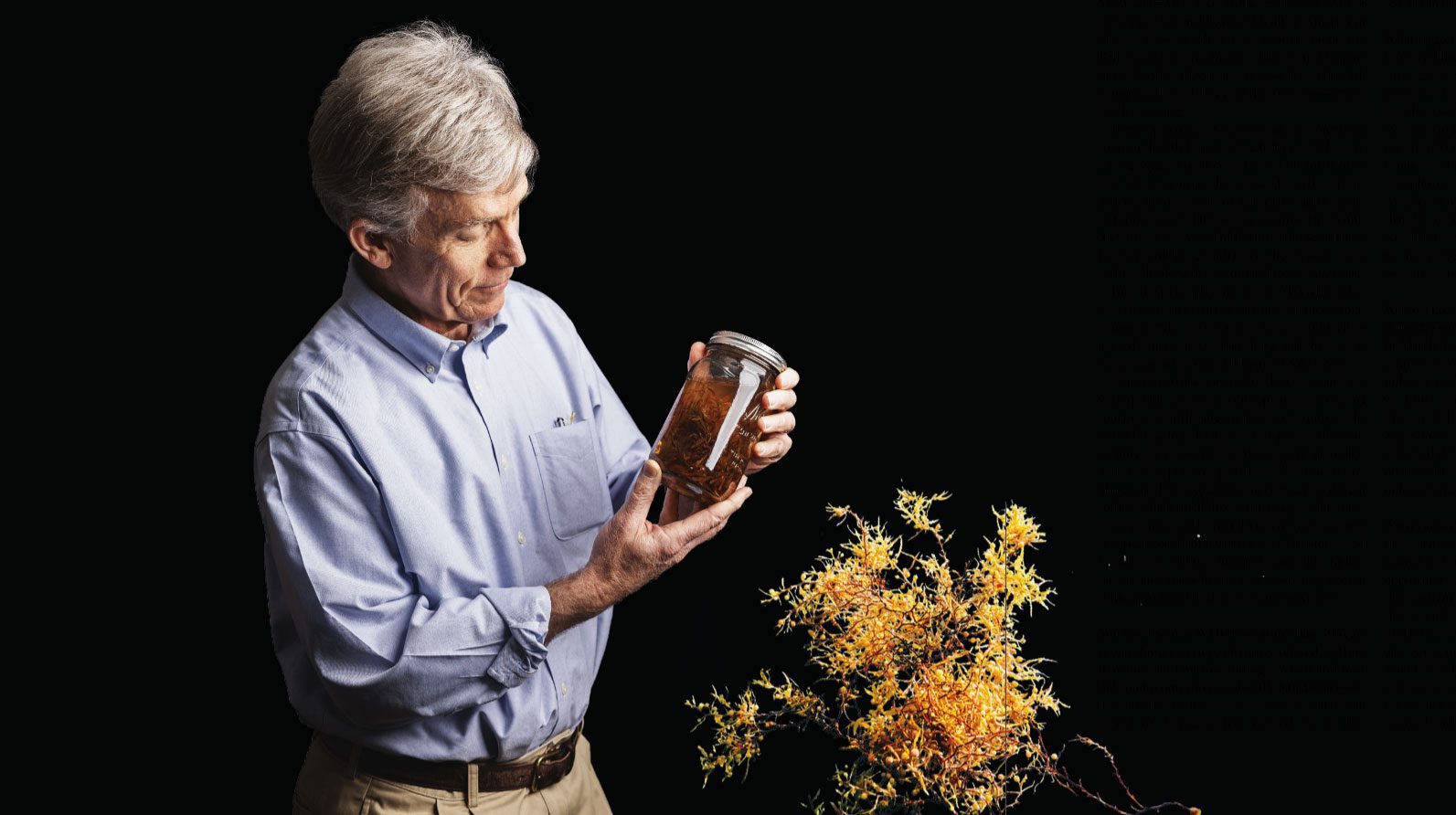

Maggie Aydlett, manager of kelp seed production at GreenWave, tests the line seeder in the field. (Photo courtesy of Ben Weiss, © Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

“Any time you can keep your bare hands out of the cold water, it makes your day nicer. This technology would be super beneficial and a huge improvement for kelp farmers,” commented Wicks.

As the fastest-growing algae on Earth, kelp is emerging as a promising resource. In the U.S., kelp farming is growing and playing a role in ocean sustainability. “The farming of kelp enriches the ocean by providing habitat and absorbing excess carbon dioxide and nitrogen,” stated Lindell. “Kelp is also the Swiss Army of product derivatives.” It is an essential feed in Asian abalone aquaculture and a valuable ingredient in bioplastics and antioxidant-rich cosmetics.

In agriculture, kelp-based biostimulants are enhancing soil health, plant nutrition, and improving crop resilience. Kelp is also being explored for biofuel production, offering a fast-growing, marine alternative to land-based sources.

“I love kelp because it cleans the water, is a great food source, and is 100% sustainable,” commented Wicks. In supporting the farmers who nurture ocean ecosystems, WHOI is advancing both marine innovation and environmental stewardship.

“This project is a great example of how ocean robotics can play a key role in combating climate change through scientific research,” said Weiss. As technology trials continue, the WHOI team is refining the device to meet farmers’ needs, paving the way for a more efficient and scalable future for kelp farming.