Top 5 ocean hitchhikers

As humans traveled and traded across the globe, they became unwitting taxis to marine colonizers

Estimated reading time: 4 minutes

Since the earliest days of ocean exploration, humans have been unwitting chauffeurs for marine species. In new waters, some of these hitchhikers have evolutionary advantages that dramatically transform native ecosystems. Let's take a closer look at the top five invasive marine species that have followed humans around the world.

1. Voracious European Green Crab

The voracious European green crab is a notorious crustacean, listed as one of the 100 worst invasive species on Earth. In the early 1800s, green crabs (Carcinus maenas) traveled from native European coasts on merchant ships. This tiny invader eventually conquered marine ecosystems on every continent except Antarctica.

Infamous for its voracious appetite, green crabs devour clams, mussels, and young oysters, tearing through commercial shellfish beds. One invasive crab can eat up to 40 small clams in a day. In some regions, green crabs are harvested as a culinary delicacy under the adage, “if you can’t beat ‘em, eat ‘em.” Despite efforts to rein in green crab populations, this highly adaptable species continues to make its mark on native ecosystems.

2. Predatory Comb Jelly

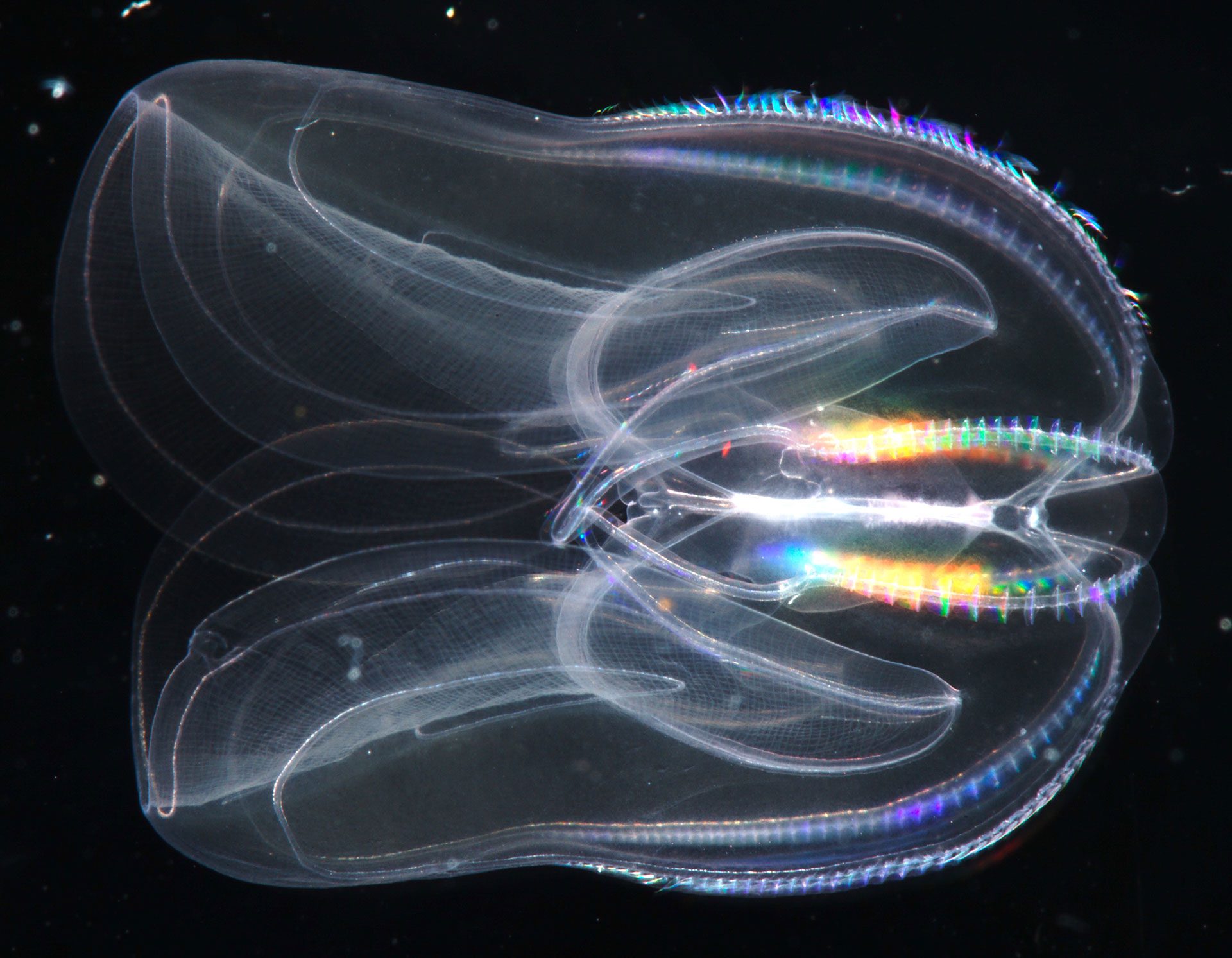

The bioluminescent comb jelly (Mnemiopsis leidyi) is mesmerizing with eight rows of cilia that refract light into rippling rainbows. Originating from the Atlantic coasts of North and South America, the comb jelly found its way into the Black Sea in the 1980s through ballast water carried by ships.

Upon arrival, this gelatinous marine invertebrate consumed massive amounts of zooplankton, fish eggs, and larvae. Devoid of natural predators, the comb jelly population surged, with an estimated 500 individuals per cubic yard in 1988. The invasion decimated the region’s $350 million anchovy and sardine fisheries, sending economic shockwaves through coastal communities. In 1997, the jellyfish Beroe ovata, a natural predator of comb jellies, appeared at the Black Sea and assisted with restoring ecological balance.

3. Tubeworm Reefs

Small but mighty, this tubeworm (Ficopomatus enigmaticus) is a species of serpulid polychaete. In the early 20th century, the species began hitching rides to new estuaries on ship hulls and in ballast water. Possibly native to the Southern Hemisphere, this globe-trotting tubeworm is now established on nearly every continent.

Once introduced, the tubeworm secretes calcareous tubes that fuse together to form reefs with thousands of worms. The massive reefs change the flow of water and trap sediments, displacing native benthic habitat and clogging waterways. Because of the sweeping changes it creates, this invasive species is considered an “ecosystem engineer.”

4. Body-Snatching Barnacle

This parasitic barnacle (Loxothylacus panopaei) could be lifted straight from a horror film. When its larva encounters a freshly molted mud crab, it begins a complete biological takeover. The parasite castrates both male and female crabs, eventually sprouting a sac from the host’s abdomen that produces its own larvae. The result is something scientists grimly call a ‘zombie crab.’

The parasite is native to the Gulf of Mexico but hitchhiked into Chesapeake Bay on shipments of oysters in the 1960s. The infection rates of the native white-fingered mud crab (Rhithropanopeus harrisii) in parts of the Chesapeake can be upwards of 75%, effectively hijacking the crabs’ ability to reproduce.

5. Killer Algae

Caulerpa taxifolia, nicknamed “killer algae,” was originally cultivated for aquariums because of its bright green fronds. But in 1984, it is believed that a strain was accidentally released from the Oceanographic Museum of Monaco into the Mediterranean Sea. From there, the species spread rapidly, carpeting seafloors with dense mats that outcompeted native seagrasses.

The invasive strain of this algae carries a substantial biological advantage: it can asexually reproduce from small fragments of itself. A single piece caught on an anchor or swept by ocean currents can start a new colony. Once rooted, eradication is nearly impossible. In the Mediterranean, this aggressive species now blankets vast stretches of seafloor and is pushing into new territory in Australia.

While preventing the spread of pesky invasive species is challenging, WHOI scientists are studying ecological impacts and supporting the development of effective management tools. Together, we are charting the course towards healthier marine ecosystems in our globalized world.

Carolyn Tepolt, “Seeing Green (crabs): Exploring adaptation in one of the world’s most resilient invasive species,” WHOI News & Insights (April 17, 2019), accessed August 22 2025, https://www.whoi.edu/news-insights/content/seeing-green-crabs/.

Jaspers et al., “Invasion genomics uncover contrasting scenarios of genetic diversity in a widespread marine invader,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, December 21 2021, 118(51):e2116211118, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2116211118

Smithsonian Environmental Research Center, “Introduced Crab Parasites Hijack Mud Crab Reproduction in Chesapeake Bay,” SERC Shorelines, published August 2015, accessed August 18 2025, https://serc.si.edu/introduced-crab-parasites-hijack-mud-crab-reproduction-chesapeake-bay#:~:text=The%20introduced%20parasite%20Loxothylacus%20panopaei,abundance%20varies%20greatly%20between%20years.

Z.J.C. Tobias et al., “Invasion history shapes host transcriptomic response to a body-snatching parasite,” Molecular Ecology (2021), DOI:10.1111/mec.16038, accessed August 19 2025.

Marine Invasions Research Laboratory, “Loxothylacus panopaei,” NEMESIS: Nonindigenous Aquatic Species Database, Smithsonian Environmental Research Center, accessed August 22 2025, https://invasions.si.edu/nemesis/species_summary/89752

Marine Invasions Research Lab, “Ficopomatus enigmaticus,” NEMESIS: Nonindigenous Aquatic Species Database, Smithsonian Environmental Research Center, accessed August 21 2025. https://invasions.si.edu/nemesis/calnemo/species_summary/68350#:~:text=Ficopomatus%20enigmaticus%20was%20first%20reported,2001).

Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, “Macroalgae: Case Study of Caulerpa taxifolia,” WHOI Science Notes, accessed August 21 2025. https://www.whoi.edu/science/B/redtide/notedevents/macroalgae/Caulerpa_7-7-00.html

U.S. Department of State, “Case Study: Caulerpa Taxifolia,” accessed August 20 2025. https://2001-2009.state.gov/g/oes/ocns/inv/cs/2326.htm#:~:text=A%20decorative%20aquarium%20plant%2C%20Caulerpa,the%20Oceanographic%20Museum%20of%20Monaco