How WHOI helped win World War II

Key innovations that cemented ocean science’s role in national defense

Estimated reading time: 2 minutes

This article printed in Oceanus Summer 2025

This article printed in Oceanus Summer 2025

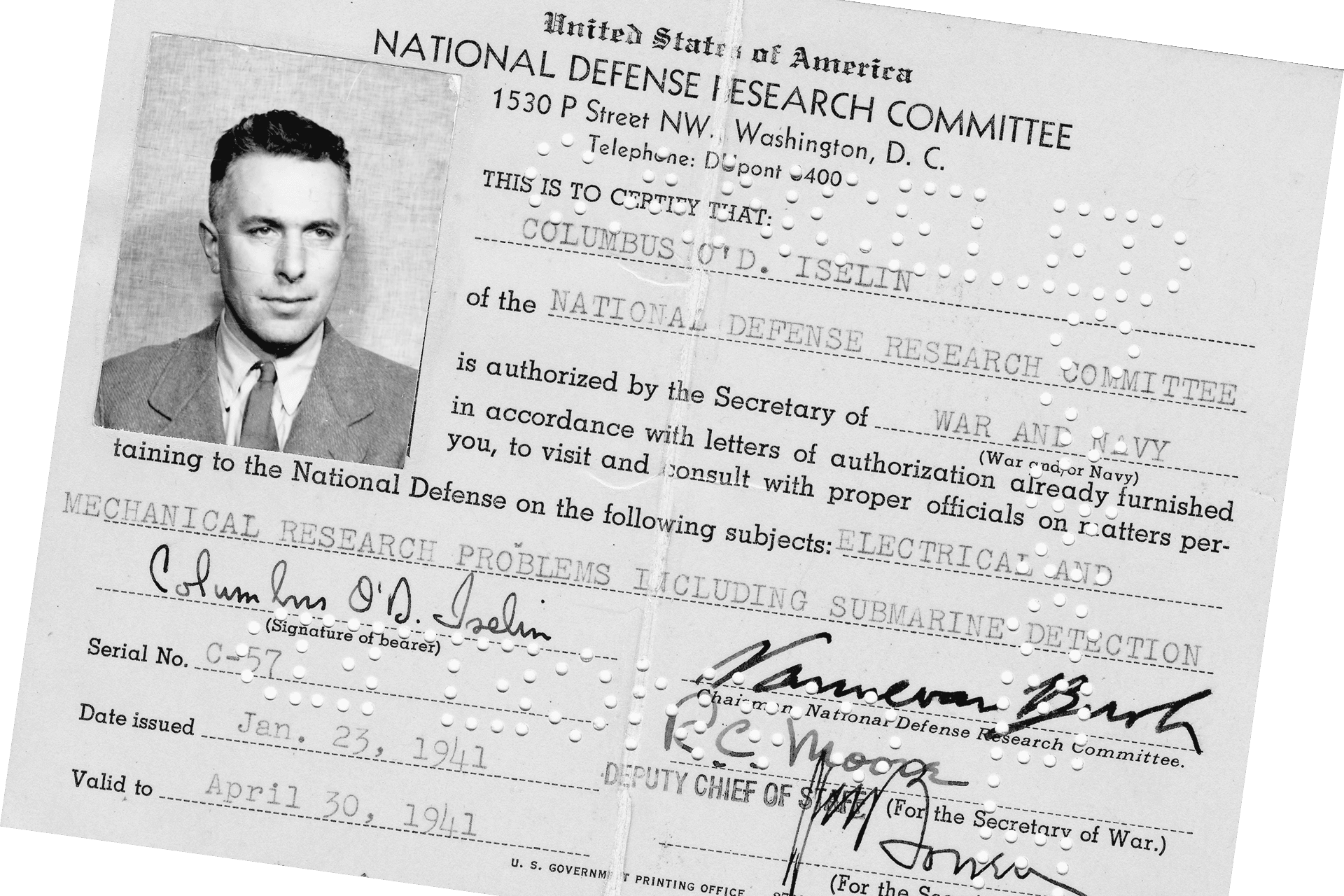

Before World War II, Columbus O’Donnell Iselin, WHOI’s second director, noted that “there was practically no liaison between oceanographers and the Navy department or its facilities.” He feared that, in the event of war, WHOI’s basic research activities would be severely curtailed, as his largely male staff went off to war.

Iselin staved off disaster by drafting a memo to the National Defense Research Committee on Aug. 5, 1940. As a former naval officer, Iselin pointed out that he was uniquely positioned to identify areas where oceanographic expertise could be used in naval research. He proposed that the Navy take advantage of WHOI’s laboratory and scientists and expand their collaboration. The committee agreed, and soon after men in uniform were wrapping the WHOI campus in barbwire and installing a guard booth out front to secure top-secret research projects.

Over the next five years, WHOI scientists and engineers worked on 37 naval research projects and 59 inventions, the most notable of which are described below:

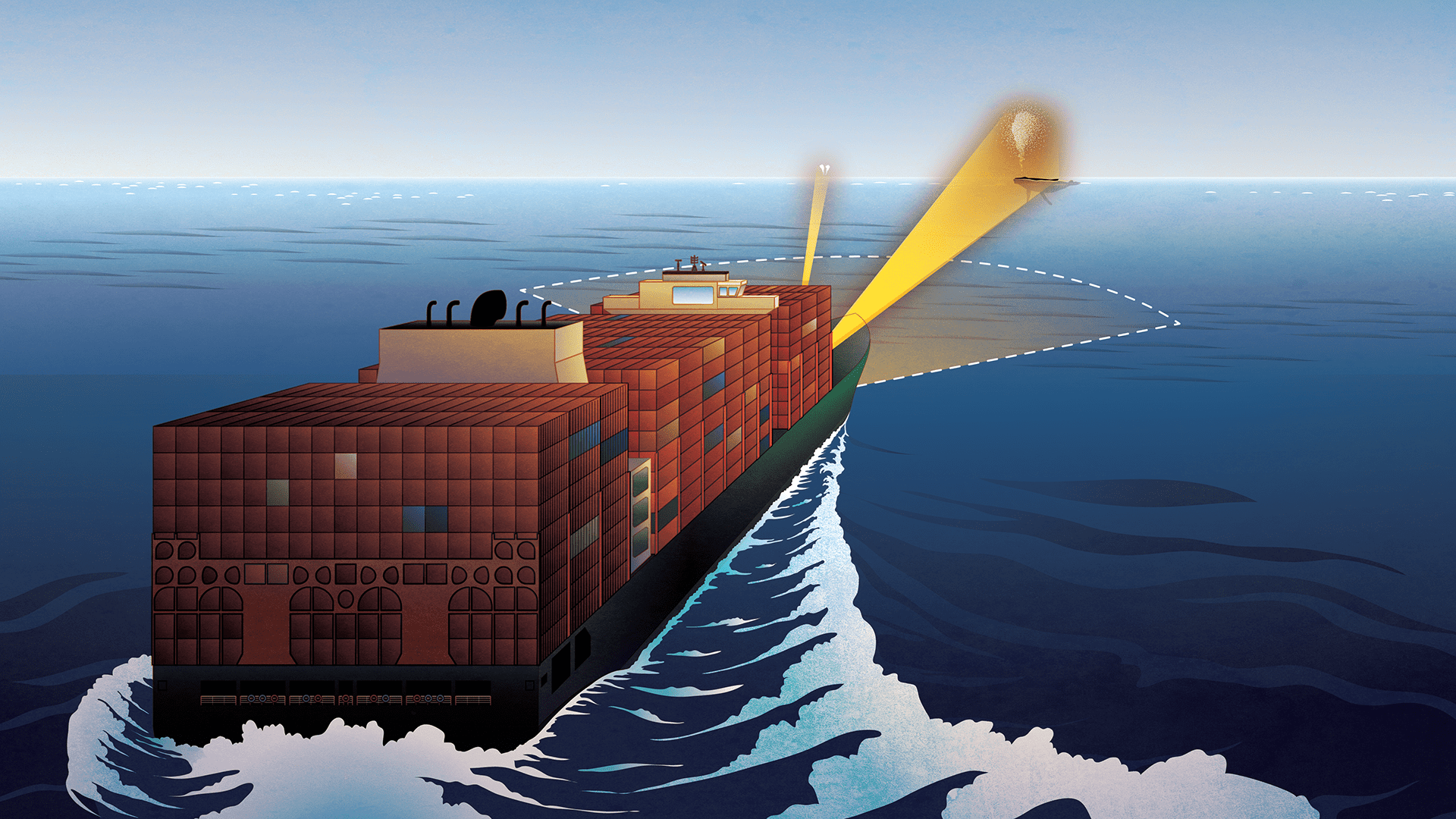

The bathythermograph

During World War II, WHOI scientists refined the bathythermograph (BT), an instrument that measures ocean temperature at varying depths, and trained naval personnel in how to gather data as they crisscrossed the oceans. BT data was compiled and published by Lt. Mary Sears in Submarine Supplements to the Sailing Directions, periodic reports that assisted submarine commanders in locating thermoclines where they could hide from enemy ships. Today, ocean temperature profiles are assessed using the expendable bathythermograph (XBT), which transmits data to ships or underwater drones for use in oceanographic studies

Ocean bottom sediment analysis

WHOI scientists compiled hundreds of navigation charts and analyzed ocean bottom sediments (gravel, mud, and sand) that affected sonar transmission and the positioning of underwater mines during the war. Early sampling techniques evolved into sophisticated, long coring systems and the development of WHOI’s world-class Seafloor

Samples Laboratory.

Underwater cameras

WHOI developed the first deep-sea cameras for oceanographic studies during World War II. Today, high-resolution cameras capture images from voyages and submersibles that aid in identifying new species of marine life and locating shipwrecks.

Underwater explosives

With project “Navy Seven,” WHOI scientists developed chemical explosives and detonators, carrying out elaborate experiments in the ocean. Due to the rattling and sometimes breaking of windows on the waterfront in Woods Hole, the group earned the nickname “The Boom Boys.” They also developed instruments and techniques to measure shock waves and study structural damage. This work formed the basis for future testing of explosive weapons and analyzing underwater volcanic eruptions.

Transmission of sound at sea

In 1937, Columbus Iselin observed the “afternoon effect,” the bending of sound waves as they passed through layers of varying temperatures due to surface water heating. These studies continued and led to WHOI’s compiling of “Sound Transmission in Sea Water,” a manual later used by the Navy for training sonar operators. WHOI scientists continued to investigate sound propagation throughout the war and helped lay the groundwork for the field of underwater acoustics.

Antifouling paints

When marine organisms build up on ships’ hulls and anchors, a process known as “fouling,” ship speeds decrease, fuel consumption goes up, and ships have to undergo time-consuming scraping in shipyards. During World War II, WHOI chemists and biologists developed a range of antifouling paints that increased the overall efficiency of naval ships by 10%. Antifouling paints today are credited with helping decrease the spread of invasive species, cutting down on harmful emissions and dampening underwater noise.