This article printed in Oceanus Summer 2023

This article printed in Oceanus Summer 2023

Estimated reading time: 3 minutes

Kaitlyn Tradd

Mechanical Engineer, Applied Ocean Physics and Engineering

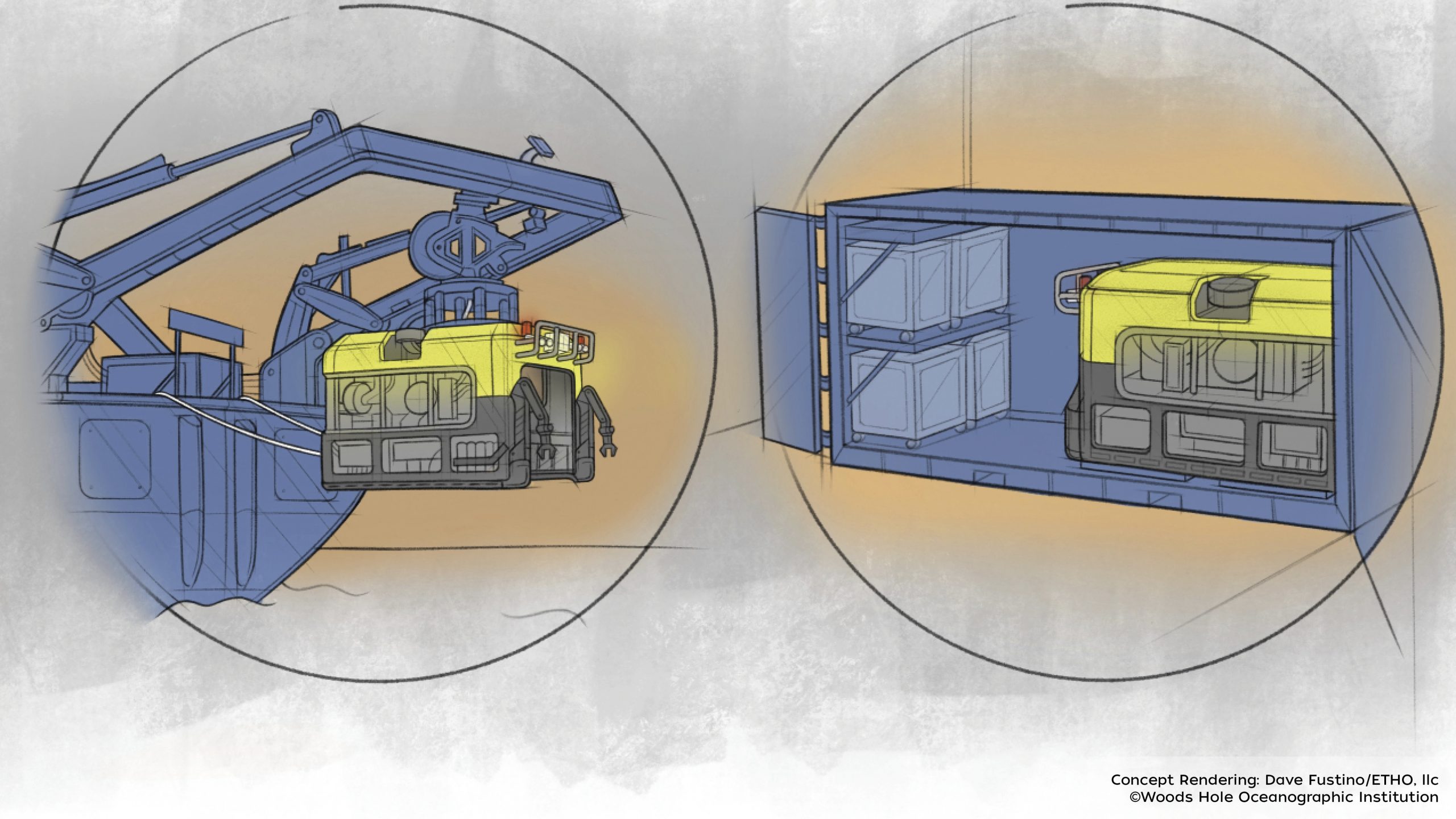

Since I came to WHOI twelve years ago, I’ve run the gamut of robotics projects. I sailed with ROVs Jason and Medea, and HOV Alvin, designed the skeletal frame of autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs) like Clio, made pressure houses and junction boxes for hybrid vehicle Nereid Under Ice and Mesobot, and designed the towable vehicle Deep-See, which helps scientists estimate life in the ocean’s twilight zone.

I can absolutely say it’s easy to develop an emotional attachment to our robots. You spend so much time and effort creating them—sweating, and literally bleeding as you put them together; scratching your knuckles on hose clamps and swearing profusely when you drop a bolt while you’re trying to finish assembling something. Over time, you can find yourself using very human language for these bots.

I was in Bermuda waiting for a robotic sediment sampler I designed called the Twilight Zone Explorer (TZEX) to return to the surface with its location after it completed its mission. I caught myself saying things like, “Now she needs to phone home when she needs to be picked up.” For me, it feels like a preview into being the mother of a teenager—I want to say, “When you’re done having fun out there, call home and I’ll come and get you.”

Using this language seems to be a kind of coping mechanism. At sea, we’re often away from our loved ones, so making the robot feel like it’s a part of your family helps you rationalize being away from home for so long.

Robots are really like our partners. I don’t see it so much as master and slave, where you’re driving and the robot is simply responding. We’re working together. And when a robot is at risk of being lost, it’s more than just your next cruise or next scientific endeavor that’s at stake. It’s a piece of you that could be gone.

Justin Fujii

Operation Lead for Autonomous Underwater Vehicle Sentry, Applied Ocean Physics and Engineering

I’ve been working with autonomous underwater vehicle Sentry for over a decade now, and when you put so much work into one robot, I feel like it’s hard not to develop an emotional connection to it. While I wouldn’t say Sentry is like a pet, it is kind of our workhorse and a family member at the same time.

Sometimes, we’ll send it to explore new deep-sea environments and it’ll come back with broken wings and propellers, and damaged skin from bumping into things at depth. I find that by taking care of the vehicle when it returns, you start to feel more attached to it. We’re refilling the robot’s fluids, downloading its data, cleaning it, and making sure everything’s still in working order for the next mission. In a way, it’s like taking care of a horse when it comes back to the stable to have its hooves reshoed.

When Sentry’s at work on the seafloor, some may think it doesn’t have a personality because it does exactly what it’s programmed to do. But sometimes it doesn’t and that’s when you see its personality really come through.

In 2013, we sent it down to the seafloor and were expecting it to make a turn and it kind of just left comms range and never came back. We had to chase after it and send it commands to tell it to come up. We eventually found it, but there’s always that inkling in the back of your mind like, “What if we lose it?” If that happened, the very purpose for being on the boat, the thing you worked so hard on for years, would be gone and you’d be left with this void. I think that feeling makes you more empathetic toward other ocean engineers when they lose a robot at sea.

Ultimately, I care so deeply about Sentry because of the team of people it has brought together. I can’t imagine losing the robot, because I can’t imagine losing them