This article printed in Oceanus Summer 2025

This article printed in Oceanus Summer 2025

Estimated reading time: 4 minutes

Five hundred years ago, Spanish conquistadors made their way to the Colombian Amazon, in search of El Dorado, a lost city of gold. Their quests often drove them to madness and ended in violence. Unbeknownst to them, El Dorado was never a city. The legend, which originated with Muisca people in the Andean mountains, was about an Indigenous leader so wealthy that he started his days by covering himself in gold from head to toe and ended them by washing it off in a sacred lake.

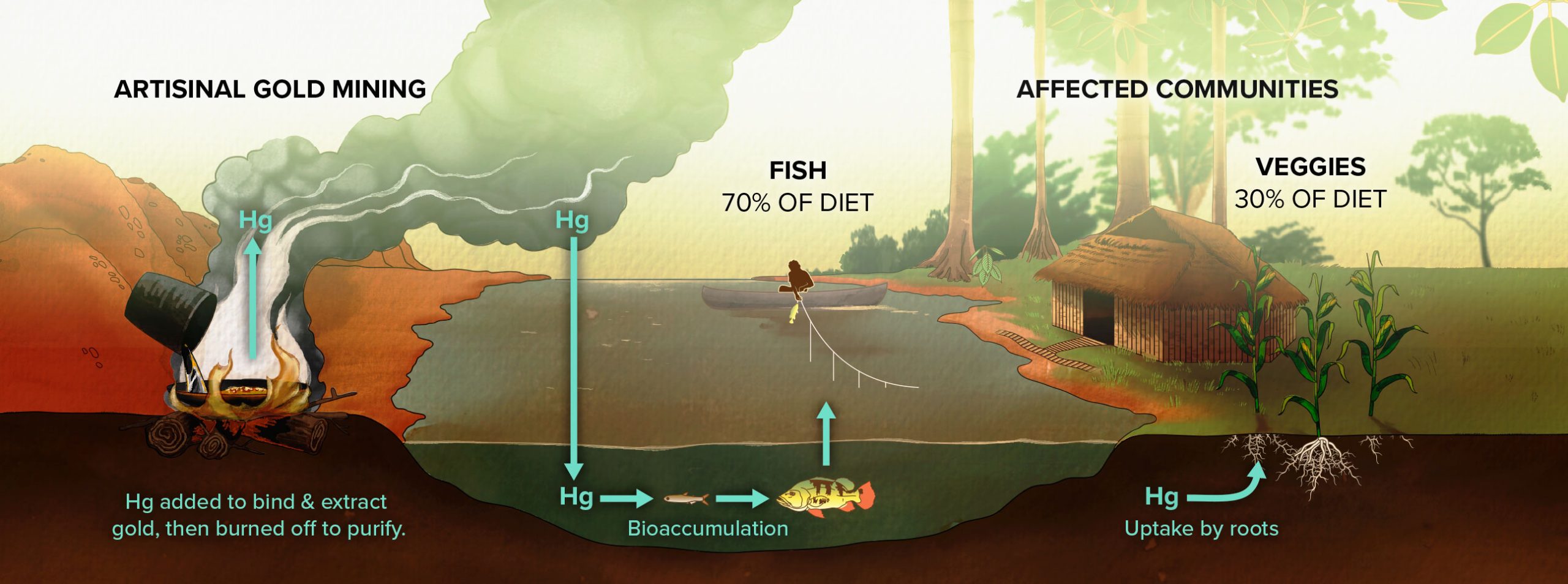

While conquistadors no longer sail the world in search of gold, their plight left a lasting impact on Colombia’s environment. Artisanal gold mining, which has been used in the region for hundreds of years, utilizes pure metallic mercury—a pervasive source of pollution—that binds to gold during the sifting process. The gold is then purified by burning off the mercury, contaminating land and water primarily relied on by hundreds of Indigenous communities.

“Indigenous peoples have a deep connection with water, often residing along major rivers where the most fertile soils for growing food are found,” said Jennifer Angel-Amaya, a Colombian geologist who focuses on toxic metals and their impacts on human health. “The major rivers carry nutrients from their headwaters in the Andes, making the floodplains rich areas for agriculture.”

A 2020 study showed that 93% of Indigenous individuals living in the vicinity of the Yaigojé Apaporis National Natural Park, in the Colombian Amazon, had much higher mercury concentrations than the World Health Organization deems safe. Health impacts include Mad Hatter’s disease—a neurological disorder characterized by mental instability and antibiotic resistance.

In 2013, the U.N.’s Minamata Convention on Mercury outlawed its use for artisanal gold mining to help prevent public health disasters caused by mercury, like the tragedy that occurred in Minamata, Japan. For decades, a chemical factory in the city dumped its wastewater into local waters. Mercury worked its way through the food web—and by March 2001, more than 2,000 people had been diagnosed with “Minamata disease,” exhibiting symptoms like loss of hearing, muscle weakness, and insanity.

But since the convention was introduced, illegal gold mining activities in the Colombian Amazon have more than doubled.

“The United Nations hadn’t realized that so many people live off artisanal gold mining,” said Laura Motta, a marine chemist at WHOI and a Colombian native. “There are whole communities that aren’t necessarily Indigenous but live in the Amazon region, and they didn’t give them many other options. So, what were they going to do to feed their families?”

“And as we keep mobilizing mercury, it eventually makes its way into the soil, which can contaminate the crops [Indigenous communities] rely on.”

—Laura Motts, WHOI marine chemist

Beyond reducing mercury pollution caused by human activities, like gold mining, the convention calls on scientists to learn more about its pathways through the environment. Motta and partners from the National University of Colombia plan to investigate this in the Colombian Amazon with a focus on the Yahuarcaca lagoon and ravine system.

“Once mercury gets into the water, biology will make the organic form of mercury, which can bioaccumulate in food webs, like fish,” Motta explained. “And as we keep mobilizing mercury, it eventually makes its way into the soil, which can contaminate the crops [Indigenous communities] rely on for the remainder of their diet.”

But questions about how mercury moves from one body of water to another—or what happens to it when contaminated bodies of water dry up—remain unanswered.

“We are going to measure the mercury stable isotopes of the planktonic communities and fish from rivers in the area. These isotopes provide a signal that can tell us exactly where the mercury is coming from,” Motta continued. “When humans eat fish, which feed on the plankton, the excess mercury that doesn’t go to their brain would be present in their hair. This will help us understand the connections between the food webs and humans, giving us a better idea of their direct link and where the exposure is coming from.”

But the research is about more than science. The team will be educating young Indigenous people about mercury contamination, so they can build a better future. Angelica Torres-Bejarano, a PhD candidate at the National University of Colombia, said she’s noticed a widespread lack of knowledge about the issue, even among Colombia’s general population.

“This lack of knowledge highlights the urgent need to generate and disseminate more accessible and understandable information about the impacts of mercury,” Torres-Bejarano said. “It is essential that knowledge about the environmental and health risks associated with this element is not restricted to academia but rather reaches communities that work directly with mercury or that, unknowingly, could be exposed to it through consumption.”

Curbing mercury pollution in the Amazon has been a slow process, but progress is being made. In October 2024, the Colombian government issued a decree emphasizing the autonomy of Indigenous peoples, giving them the authority to regulate natural resources within their territories. While this can be seen as a win for Colombia’s Indigenous communities, more solutions are needed.

“Effective enforcement of these regulations requires the participation and collaboration of government and civil institutions. Environmental leaders, particularly Indigenous leaders, become targets when they oppose illegal mining in their territories,” Angel-Amaya said.