Carbon dioxide in the atmosphere traps the sun’s heat and helps warm the planet. Too much carbon dioxide drives global warming and climate change. But at the ocean’s surface, the gas moves between air and water. Once in the ocean, some of it can be locked away to help prevent more warming. Marine microbes play an important role in this process.

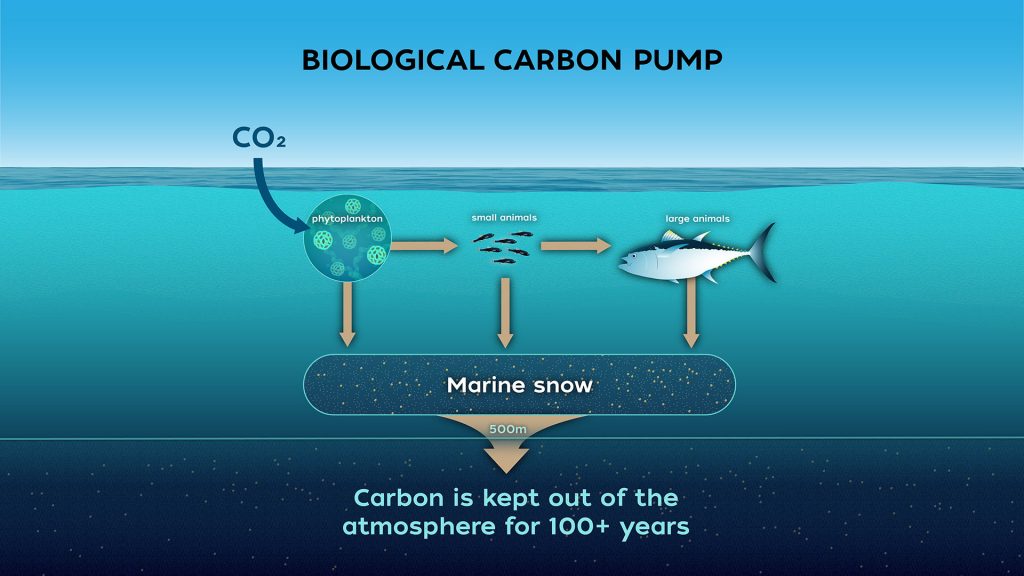

When sun shines on the ocean’s surface, tiny phytoplankton get to work. These microscopic, plant-like algae pull carbon dioxide from seawater. Then they use sunlight to turn it into food. That food feeds the ocean, forming the base of the marine food web. Small zooplankton snack on phytoplankton. And bigger organisms snack on them. As consumers process the food they eat, they release carbon dioxide back into the ocean.

But not all of that carbon stays near the surface. Over time, through messy eating and plenty of pooping, some of the carbon sinks through the ocean’s depths, falling as marine snow. Some of these fluffy leftovers are visible, but others are too small to see without a microscope. If they reach the deep ocean, the carbon they contain can be locked away for hundreds or even thousands of years. In this way, the ocean has slowed global warming by storing vast amounts of carbon, and scientists recently discovered part of the reason why: tiny marine microbes.

Although the open ocean looks empty, its waters teem with microscopic life. An assortment of single-celled organisms fills every teaspoon of water. A single liter of seawater contains millions of microbes. They’re everywhere, an invisible force that transforms carbon as it moves through the water column.

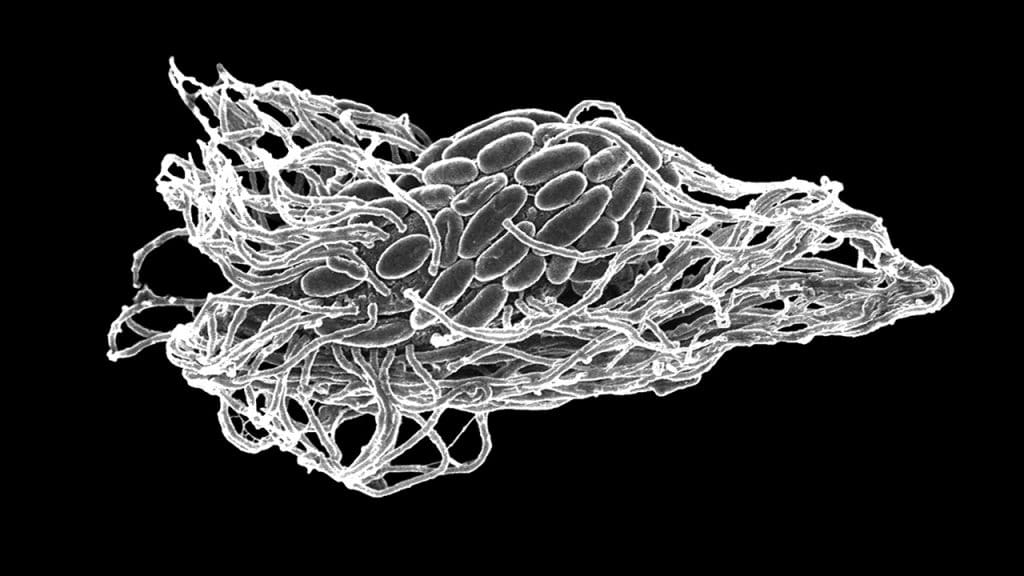

Bacteria and another group of single-celled microorganisms called Archaea thrive in the ocean. These cells chow down on the tiniest bits of marine snow and break it down into even smaller carbon-containing pieces. Microbial snacking also changes the structure of carbon-based molecules. Some pieces break down easily and can be used for food. Others can’t. When bacteria eat, they change much of the carbon in marine snow to a form that is difficult to break down by other organisms. This helps keep carbon stored in the ocean, slowing its return to carbon dioxide.

Viruses also play a big role. These tiny invaders inject their genetic material into bacteria and Archaea. The single-celled microbe then creates many copies of the virus’s genes. When the cell is full, it breaks open, spilling new viruses and the cell’s guts into the ocean. This releases a variety of molecules into the ocean, some of which are difficult for other organisms to use.

Because microbes can’t easily break down this carbon, it is oxidized much more slowly. As a result, it can take decades, centuries, or even millennia before it can form carbon dioxide again. This makes marine microbes a critical part of the ocean’s ability to absorb carbon dioxide and an essential part of our fight to slow climate change.

learn more

Marine Microbes

Microbial life can be found throughout the ocean, from rocks and sediments beneath the seafloor, across the...

Biological Carbon Pump

The biological carbon pump moves carbon from the surface ocean to the deep sea, helping store atmospheric...

Carbon Cycle

Carbon is the building block of life on Earth and has a powerful impact on the planet’s...

Life at Vents & Seeps

Hydrothermal vents and cold seeps are places where chemical-rich fluids emanate from the seafloor, often providing the...

Azam, F. & A.Z. Worden. Microbes, molecules, and marine ecosystems. In: Microbial Carbon Pump in the Ocean (ed. by N. Jiao, F. Azam, & S. Sanders), p. 16-17. 2011. AAAS.

Behrendt, L. et al. Microbial dietary preference and interactions affect the export of lipids to the deep ocean. Science. Vol., 385. September 13, 2024. doi: 10.1126/science.aab2661

Jiao & F. Azam. Microbial Carbon Pump and its significance for carbon sequestration in the ocean. In: Microbial Carbon Pump in the Ocean (ed. by N. Jiao, F. Azam, & S. Sanders), p. 43-45. 2011. AAAS.

Zakem, E.J. et al. Functional biogeography of marine microbial heterotrophs. Science. Vol. 388. May 22, 2025. doi: 10.1126/science.ado5323