At the ocean’s surface, sunlight provides energy to tiny phytoplankton. They use that energy to make a form of food called glucose. When animals eat the phytoplankton, that energy gets passed along the food chain. But deep in the ocean, there is no sunlight. So where do organisms on the ocean floor get the energy they need to survive? Some use chemicals seeping from deep-sea vents, cold seeps, whale falls, and wood falls.

Like phytoplankton at the surface, tiny deep-sea microbes also use energy to make glucose. But instead of using energy from sunlight, these microbes rely on chemical reactions. The chemicals they use come from Earth’s crust.

In some areas of the ocean, water filters down into the seafloor. There it picks up minerals, gases, and other chemicals before returning to the surface. Which chemicals are found in the returning water depends on the location. Hydrothermal vents spew very hot fluids that tends to have a lot of hydrogen sulfide in it. Cold seeps, on the other hand, release cold water that’s rich with methane.

Both hydrogen sulfide and methane react with oxygen in seawater. When they do, they release energy. Deep-sea microbes use this energy to make glucose in a process called chemosynthesis. But those reactions only happen when the chemicals coming from the vent or seep interact with the oxygen in seawater.

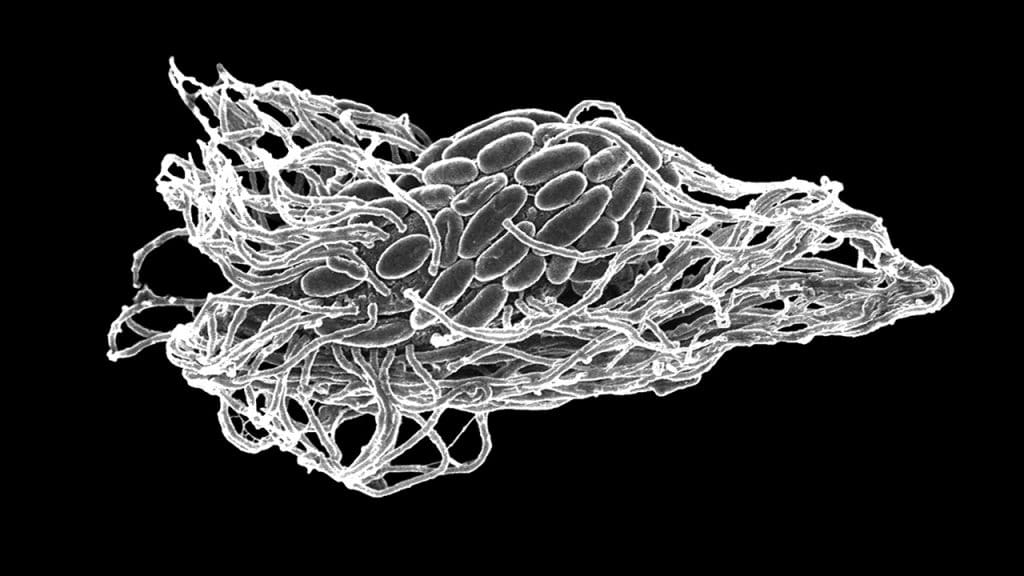

It’s difficult for a single-celled organism to be in the right place at the right time to capture that energy. So instead of swimming freely in the water, many live inside the bodies of deep-sea animals.

Hydrothermal-vent and cold-seep ecosystems include a variety of animals. Some, like tubeworms and mussels, stay anchored in one place. Others, like deep-sea shrimp, snails, and crabs, move about. The animals provide the microbes with a place to live. They also provide everything the microbes need for their chemical reactions. In exchange, the microbes share the glucose they make, feeding the animal from within. This relationship is called symbiosis.

Not all microbes live inside animals. Some swim freely in the water. Others form thick microbial mats. Deep-sea animals don’t always get their energy from symbiotic microbes, either. Mussels and tubeworms also filter tiny organisms like free-swimming microbes out of the water when they feed. Shrimp, crabs, and snails graze on microbial mats and other small animals.

The existence of these deep-sea ecosystems has only been known for a few decades. WHOI scientist Richard Ballard spotted the first hydrothermal vent near the Galapagos Islands in 1977. Oceanographers have since found them in every ocean, and they discover more sites each year. These unique ecosystems provide us with important information about how life may have begun on Earth. And they might hold the key to searching for life on other planets, especially those that get little sunlight but have deep-ocean vents and seeps.

learn more

Marine Microbes

Microbial life can be found throughout the ocean, from rocks and sediments beneath the seafloor, across the...

Life at Vents & Seeps

Hydrothermal vents and cold seeps are places where chemical-rich fluids emanate from the seafloor, often providing the...

Dick, G.J. The microbiomes of deep-sea hydrothermal vents: distributed globally, shaped locally. Nature Reviews Microbiology. Vol. 17, p. 271. March 13, 2019. doi: 10.1038/s41579-019-0160-2.

NOAA. Ocean Exploration. Chemosynthesis Fact Sheet. https://oceanexplorer.noaa.gov/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/chemosynthesis-fact-sheet.pdf

Smith, C. Chemosynthesis in the deep-sea: life without the sun. Biogeosciences Discussions. Vol. 9, p. 17037. 2012. doi: 10.5194/bgd-9-17037-2012.