Estimated reading time: 3 minutes

Recent reports of record-setting snowfall in Antarctica suggest that after decades of steadily losing ice, Antarctica’s ice cover could finally be reversing course. That would be welcome news, and it’s easy to think the change means ice sheets are no longer melting. But in the lifespan of an ice sheet, these reversals are unlikely to have a major impact in coming centuries.

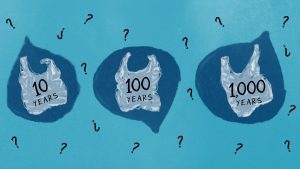

“It seems like this is a good sign,” WHOI glaciologist Catherine Walker says of the increased snowfall. But despite the recent addition, the overall trend is that the ice sheet is shrinking. In part, it’s a question of time scales. The “mass balance of an ice sheet is comprised of processes that occur over hundreds to thousands of years,” she says. Compare that to a one- or two-year change, and it quickly becomes apparent this snowfall is likely a temporary feature.

Ice sheets build up over millennia through snowfall, which then melts at the edges. Over time, the weight of new snow compacts deeper layers into dense sheets of ice that slowly spread across the land like a pancake. The edges of that pancake eventually reach the Antarctic coastline, where glaciers slide into the sea, melt, and calve icebergs, processes that release large quantities of fresh water into the ocean.

Such processes have long happened in Antarctica, as the sheer weight of the ice forces the ice sheets to spread. But melting and calving have been happening faster as warmer temperatures increase melting along the Antarctic coastline, where summer temperatures now frequently reach 10 degrees Celsius (50 degrees Fahrenheit). Such temperatures accelerate the rate of melting along the edges—and the rate at which the ice sheets slide out over the warming waters of the Southern Ocean and eventually break free.

Snowfall on the continental interior, according to Walker, is like money in the bank. “You could say that you get a paycheck every week, but if you spend more than you made, it's like, yeah, you are adding to it weekly, but you're spending more than you put in. Occasionally you get a big holiday bonus, like the large amount of snowfall recently, but overall, you're still in a net negative,” Walker says. That, she notes, is the situation for Antarctica right now. And as temperatures continue to warm, losses will continue to outstrip gains.

Paradoxically, the heavy snowfall is likely the result of warming air temperatures. “Things like atmospheric rivers increasingly happen in Antarctica now,” Walker says. These drop a massive amount of precipitation because warmer air holds more moisture, super-charging these snowfall events. Such record-setting snowfall is mostly affecting only one of the continent’s ice sheets.

“Antarctica is actually made up of two different ice sheets. There's the West Antarctic ice sheet and the East Antarctic ice sheet,” Walker explains. Separated by the Transantarctic Mountain range, the western ice sheet flows toward the western hemisphere, and the eastern flows toward the east.

East Antarctica holds about ten times the volume of ice as West Antarctica. It’s also the ice sheet that’s recently gained mass. West Antarctica, on the other hand, is losing ice at ever-increasing rates—and it’s a harbinger of what the East Antarctic sheet may experience in the future.

“That section will start melting into the ocean more as well, as things continue to warm,” Walker says. “The west is melting rapidly now; perhaps within 100, 200 years, the eastern part will start acting like that as well.” And when it does, it will release vast quantities of water into the ocean, raising sea levels around the globe.

On the other side of the world, the Greenland ice sheet continues to steadily shrink. “It gains mass, transiently, through snowfall events,” Walker says. As in Antarctica, a warmer atmosphere leads to more precipitation falling on the existing ice sheet. “But in the summers, in Greenland, almost the entire ice sheet can get above freezing, and so the precipitation will fall as rain. And that actually accelerates melt, because if you're putting water on top of ice, it will melt further.”

The melting ice runs off into the North Atlantic, raising sea levels. Although model projections have plenty of uncertainty, most foresee the Greenland ice sheet shrinking to half its current size over the next 500-700 years. That will have more immediate impact on sea level rise rates for the U.S. East Coast and Europe, Walker notes. “Because it's right there in the North Atlantic, where we are.”