By Daniel Hentz

DANIEL: We can all imagine the devastation hurricanes bring ashore—from destroyed homes, to flooded streets, flattened forests and power outages of epidemic proportions.

Well it turns out that hurricanes could be just as devastating to denizens of the deep ocean.

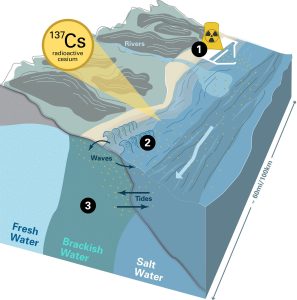

At sea, a hurricane’s high-velocity winds violently churn the surface water, producing large waves that ripple out from the storm’s epicenter. Over time, these waves begin to collide with one another and combine their energy. When they become big enough, they can transfer this growing energy all the way down to the seafloor below.

AUDIO: *Ambient underwater noise*

DANIEL: If these deep, growing, underwater energy waves collide with something solid and abrupt like the American continental shelf…

AUDIO: *Rumbling of an earthquake*

DANIEL: …they can produce something a lot like a 3.5 magnitude earthquake—underwater.

Wenyuan Fan has appropriately named these underwater tremors, “stormquakes.”

WENYUAN: Stormquakes, the force is generated in the ocean.

DANIEL: Fan is a former post-doctoral scholar at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (or WHOI for short). He’s now a seismology professor at Florida State University.

In 2018, he and his colleagues studied data from the seismic stations that span the U.S. continent—part of a larger nationwide program called Earthscope.

Initially, they set out to study earthquakes on land, along the coasts. But as they worked their way through data from land-based seismic stations, they noticed something peculiar.

WENYUAN: We start to see all these events popping up near the offshore British Columbia region.

DANIEL: At first, his team thought these seafloor seismic events off the western coast of Canada were caused by earthquakes from faults on land. But by analyzing the energy waves, Fan realized that the source of these tremors was actually far out at sea. What’s more, these seafloor quakes followed a pattern.

WENYUAN: After processing for a few years, we start to realize, such things have clear seasonality.

DANIEL: That seasonality struck Fan as odd, because earthquakes can happen at any time of year.

WENYUAN: It’s very unlikely to be an earthquake, because earthquakes [don’t] have seasonality. [It’s] more likely to be something that has seasonality, for example: weather.

DANIEL: Specifically, storms and hurricanes. Fan’s team identified more than fourteen-hundred stormquake events from 2006 to 2015. Many were triggered by relatively small storms. But the biggest stormquakes—those caused by major hurricanes—radiated more than 90 miles—that’s more than half the size of Boston in every direction.

But, Fan says, not every storm over the ocean will generate a stormquake on the seafloor. Two key factors come into play. The first is the topography of the ocean bottom. To generate a stormquake, the energy from a storm needs to encounter some underwater feature that juts out from the seafloor— the continental shelf, a seamount, or an ocean bank, for example. The second factor is the depth of the water, also known as the ocean’s bathymetry.

WENYUAN: When the bathymetry is not right, stormquakes will not be generated.

DANIEL: The deeper the water, the more energy is needed to generate waves that can actually reach the seafloor. If the water is too deep relative to the storm’s energy, the waves won’t reach the bottom—so, no stormquake.

British Columbia, like New England, has its own, abrupt, shallow continental shelf—the perfect conditions for a stormquake. But along the U.S. East Coast, from New Jersey going south toward Florida, ocean depth changes more gradually as you approach the shore. In regions such as that, Fan says…

WENYUAN: very strong storms may not be able to cause stormquakes at all. For example, Hurricane Sandy, Superstorm 2012, didn—t generate any stormquakes.

DANIEL: On land there are many kinds of natural disturbances— from forest fires to tornadoes and blizzards—all affecting an ecosystem’s habitats and stability. Could a stormquake play a similar role on the ocean floor?

WENYUAN: It is indeed a natural disturbance to the ecosystem for that particular region.

DANIEL: Along with WHOI scientists Steve Elgar and Britt Raubenheimer, Fan intends on proposing a new study that will gain insights into how regular a disturbance stormquakes truly are. To do this, the team aims to install an array of seismometers and other sensors along Georges Bank, about 180 miles southeast of Massachusetts, to record the energy waves that are making it to the seafloor.

WENYUAN: The discovery of stormquakes, to me—we really push our intellectual understanding of what’s around us. It makes me feel very humble about how little we know about nature.

DANIEL: Another question Fan is interested in answering is how climate change could affect this newly discovered phenomenon. As our ocean warms, hurricanes are growing stronger, producing more consistently powerful waves. Fan believes this could intensify stormquakes, at least for northern storms that linger along the continental shelf.

For Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, I’m Daniel Hentz.

Research behind this story was funded through the Seismological Facilities for the Advancement of Geoscience and EarthScope (SAGE) Proposal of the National Science Foundation. Music from Podington Bear and Epidemic Sound. Editing support for this story was provided by Véronique LaCapra. This episode is a production of © Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution.

Image and Visual Licensing

WHOI copyright digital assets (stills and video) contained on this website can be licensed for non-commercial use upon request and approval. Please contact WHOI Digital Assets at images@whoi.edu or (508) 289-2647.