- SAFETY MEETING?Tioga Captain Ken Houtler, center, leads a safety debriefing before departing the dock in Newburyport to begin recovery of buoys and tripods that hold instruments on the riverbed.

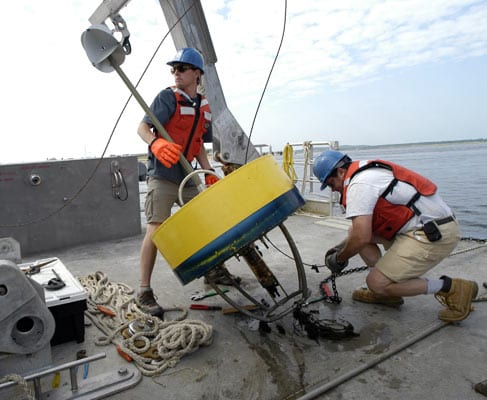

- UP ON DECK—Dave Ralston, left, and Senior Research Assistant Jay Sisson, with a buoy recovered near the mouth of the Merrimack. Jay connects the buoy anchor chain to a winch cable to haul up the anchor, which is a 200-pound cylinder of steel.

- STOWING FOR THE TRIP—From left, Dave Ralston, Rocky Geyer, and Jim Lerczak stow recovered buoys near Tioga’s bow. The instrument protruding from the bottom of the buoy measured near-surface conductivity and temperature every five minutes for about two months. Conductivity and temperature are used to derive salinity. Salinity readings from both the surface and riverbed are used to derive changes in stratification throughout the tidal cycle. In the study, stirring and mixing of salt and fresh waters is measured along three axes—vertically, across the width of the river, and along its length. This data lays the foundation for quantifying dispersion properties of the estuary.

- TOO CLOSE FOR COMFORT—Most buoy recoveries went without a hitch, but this one, farthest upstream, involved disentangling the buoy line from a yacht mooring (white sphere) that had been placed too close to the buoy. The oblique angle of biofouling on the yellow buoy indicates that the buoy was heeled over most of the time due to swift tidal currents in the river.

- CLEAR THE DECK—Postdoctoral scholars Malcolm Scully and Dave Ralston guide anchor chain into a deck box. The steel anchor is visible aft.

- RECORDING TEAM—Summer Student Fellow Megan Jamison, left, records instrument serial numbers with help from postdoctoral scholars Dave Ralston and Malcolm Scully. Serial numbers are used later to match the data with the location of the recordings. Seven aluminum instrument tripods were placed on the bottom of the Merrimack to record various properties for about two months. The white cylinder records temperature and conductivity. The red cylinder is an acoustic Doppler current profiler, which records the flow rate of overlying water in 25-centimeter intervals nearly to the surface. Strapped to a horizontal cross bar, and barely visible, is a blue cylinder that measures pressure, used to derive changes in sea level related to tidal cycle and changes in fresh water flow. It measures sea level to within less than 1 centimeter.

- COME HERE WATSON, I NEED YOU—“On every cruise, there has to be at least one thing that goes wrong,” said WHOI scientist Rocky Geyer, “and for us, this is the one thing.” Three instrument tripods that were placed in high-traffic areas did not have surface buoys. Instead, buoys were tethered to a recovery line and submerged with the tripods. The buoys would float to the surface when they received a series of specific acoustic pings, like a telephone tone. Then the recovery line could be snagged and the tripod winched to the surface. Here, postdoctoral scholar Malcolm Scully holds a transmitter over the side to trip the acoustic release. After several failed attempts to trip the release on one of the tripods WHOI physical oceanographer Jim Lerczak (pointing) and Geyer decided to drag for the tripod.

- DO WE HAVE A NIBBLE?—Dragging for a lost tripod involves hanging a grappling hook over the stern and, knowing the Global Positioning System fix of the tripod, piloting the boat back and forth over the area, in hopes of snagging the hook on the tripod. Senior Research Assistant Jay Sisson, right, keeps tension on the grappling line, while Tioga Captain Ken Houtler (blue shirt) and WHOI scientist Rocky Geyer help secure the line. After several hours of unsuccessfully dragging for the tripod, it was decided to send divers to find the tripod, just 20 feet down. But they had to wait for slack low tide, at 5 a.m. the next day. Otherwise, the divers might not have been able to maneuver in the swift current.

- REPORT FROM 20 FEET DOWN ?WHOI scientist Rocky Geyer, left, confers with divers Pat Lohmann, center, and Jay Sisson, after they located the lost instrument tripod. It turned out that the tripod, which is about 2 feet high and houses about $30,000 in instruments, was nearly completely buried by a migrating sand wave. Jay and Pat excavated it by hand to expose enough of the frame to attach a cable and winch it aboard Tioga.

- LOST,THEN FOUND?WHOI physical oceanographer Jim Lerczak unbolts the acoustic Doppler current profiler (ADCP) from the last recovered tripod. The circular patterns at the top of the ADCP are the transducers that emit sound. Properties of the backscattered sound are used to determine the current velocity of the overlying water.

- HEADING HOME —Mate Ian Hanley steadies Tioga at the end of the cruise, preparing to leave Newburyport with a wealth of new data from the dynamic Merrimack River estuary.

SEARCH RELATED TOPICS: Rivers, Estuaries, & Deltas

Image and Visual Licensing

WHOI copyright digital assets (stills and video) contained on this website can be licensed for non-commercial use upon request and approval. Please contact WHOI Digital Assets at images@whoi.edu or (508) 289-2647.