- On a clear day, recovering an underwater vehicle could be relatively easy. ?Clear,? in this case, referred not to the sky, but to the ocean. Using sound signals, scientists guided the robotic vehicle Puma to surface in a calm, open pool of water in the ice pack and head right toward WHOI engineer John Kemp in a crane-operated basket, almost like a good dog coming home to poppa (left). Oden?s Able Seaman Stefan Borstad crooked the crane?s elbow as far down as it could go and extended its forearm to get the basket as close as possible to the water line. Kemp reeled in Puma, and Borstad reeled in Kemp.

- Clear days were rare, however, and most recoveries posed nerve-wracking challenges. More ice required more maneuverability, so Oden?s small boat, Hugin, was dispatched to find and recover vehicles surfacing in the ice pack.

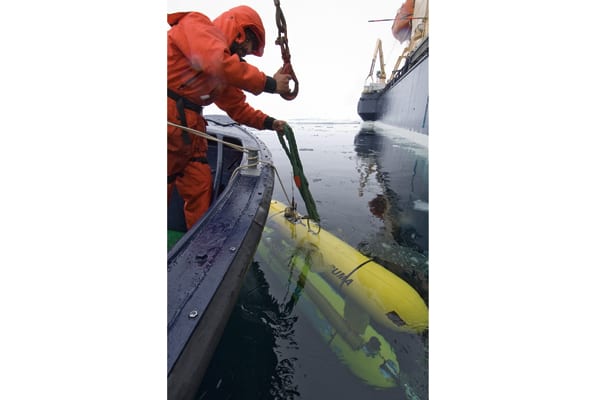

- WHOI researchers Hanu Singh and Mike Jakuba secure Puma by ropes to Hugin, which towed the robot back to Oden.

- Singh attaches Puma to Oden?s crane for hoisting back on board the icebreaker.

- From Polar Discovery, July 21, 2007: Sometime after 7 a.m. Friday, about 3,700 meters, or 2.3 miles, under the Arctic Ocean ice cap, the robotic vehicle Puma lost a thruster on a mission to search for plumes from hydrothermal vents on the seafloor. Scientists, engineers, and the crew of the icebreaker Oden all mobilized to try to get the hobbled vehicle back to the surface, to guide Puma to a rendezvous with Oden in the shifting ice pack, and to make a hole in the densely packed ice for Puma to surface safely.

- With Oden?s master, Mattias Peterson, directing operations, and its second officer, Thomas Stromsnas, working the ship?s controls, the icebreaker mashed broken chunks into smaller pieces. In this fish-eye lens view, you can see how the ship circled the pieces, herding them into the center. The ship then tried to push the pieces to one side, to clear a patch of open water for Puma. But the ice pack was unforgiving today. The ice moved backed quickly, filling the hole again, and swarming the ship?s hull.

- Meanwhile, MIT/WHOI graduate student Clay Kunz (center) and others on the autonomous underwater vehicle (AUV) team were holed up in the AUV control van, calculating Puma?s slow ascent, tracking its position, and nudging the vehicle via computer commands toward Oden. The drama took hours to unfold. Chief Scientist Rob Reves-Sohn?s cuticles paid a price. ?I wish fingernails grew faster,? he said. WHOI engineer John Kemp (left) gets an update on the situation.

- When Puma nears the ship, the ship?s transponders can no longer pick it up well, leaving the AUV team unable to locate it precisely. WHOI scientists Susan Humphris and Tim Shank and helicopter pilots Sven Stenvall and Geir Akse were dispatched with a receiver that could hear a sound beacon on Puma?a device normally used to locate people trapped under avalanches. Stenvall flew the helicopter around the boat with the receiver dangling by a cable just above the ice, listening for telltale signals from Puma, somewhere nearby and under the ice. Then Shank spotted Puma?s blinking strobe light and a bit of its yellow ?skin? in a tiny gap between ice floes, hugging Oden?s hull on the portside bow.

- There?s a joke aboard ship that John Kemp will miss no opportunity to get into a ship?s crane-operated metal basket. Oden?s chief officer, Ola Andersson, lowered the basket toward the ice, reaching slightly underneath the ship and along its hull. For several tense minutes, neither Kemp nor anyone else saw Puma, and we wondered if it had disappeared under the ice or under the ship. Then Japan?s National Institute of Advanced Science and Technology geochemist Ko-ichi Nakamura saw Puma?s nose peeking out from under an ice floe. Andersson maneuvered Kemp toward it. With a long metal pole, Kemp pushed aside ice floes to free Puma. Nearly 22 hours after he had let Puma loose, Kemp grabbed hold of it again and brought it back on board.

- Two days later, Puma?s robotic sibling, Jaguar, surfaced somewhere under a seemingly endless blanket of white. Oden?s helicopter flew low, dangling a receiver just above the ice to listen for a sound signal from Jaguar. After more than an hour, a signal finally came. Pilot Sven Stenvall dropped a red-painted piece of wood on the ice to mark Jaguar?s location underneath. Oden broke ice and up popped Jaguar. Mattias Peterson, Oden?s captain, expertly and gingerly maneuvered the icebreaker toward it, trying to avoid accidentally running over it, pushing damaging ice floes into it, or stirring up the ice too much and losing the vehicle again.

- WHOI engineer John Kemp (red suit) and Ulf Hedman, expedition leader from the Swedish Polar Research Secretariat, were lowered in a metal basket to the ice to recover Jaguar. Each man was armed: Hedman with a shotgun in case of polar bear; Kemp with a pole and a rope and safety harness so he could jump safely from one ice floe to another. But by the time they reached the ice, Jaguar had suddenly disappeared again, and they could not relocate it.

- More fretful hours passed, but at last, a crack opened in a large ice floe that had pinned Jaguar. Stenvall landed on the floe, and co-pilot Geir Akse hooked a line to Jaguar (note the red marker).

- Oceanographers often say their underwater vehicles ?fly? through the ocean above the seafloor. Jaguar flew through the air. The helicopter delivered it to a pool of open water near Oden, where it was brought aboard as ice floes rushed in against the hull. During the expedition, Puma and Jaguar were launched eight times. To the relief and delight of WHOI scientists Rob Reves-Sohn and Hanu Singh, the number of recoveries equaled the number of deployments.

SEARCH RELATED TOPICS: Sea Ice / Underwater Vehicles

Image and Visual Licensing

WHOI copyright digital assets (stills and video) contained on this website can be licensed for non-commercial use upon request and approval. Please contact WHOI Digital Assets at images@whoi.edu or (508) 289-2647.