DANIEL: I’m Daniel Hentz from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. It seems that every day commercial fisheries are facing new environmental obstacles here in New England. One of those obstacles occurred last month, when warm water from the Gulf Stream seeped into fishing and lobstering grounds around Block Island.

GLEN: The fishing almost immediately cut off for certain species along the bottom.

DANIEL: That’s Glen Gawarkiewicz, a physical oceanographer and senior scientist at WHOI.

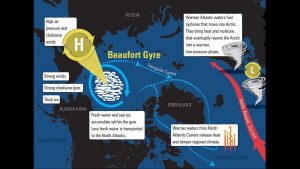

GLEN: Essentially what happens is the Gulf Stream becomes unstable. It makes very large meanders. And eventually these meanders break off and form an eddy.

DANIEL: That “intrusion” of warm water that he’s talking about is also known as a warm core ring, something that Glen says most fishing fleets couldn’t predict (or prepare for) without adequate data and the know-how to interpret it.

GLEN: They can be 60 miles across and they can persist for months. And what’s so tricky about these intrusions is that they can actually move across the continental shelf at mid-depth and they may be anywhere from, say, 20 to 60 feet thick in the middle of the water column.

DANIEL: But Glen has been working to bridge this gap in understanding of oceanographic processes. Since 2014, he’s been working directly with fishermen through the Shelf Fleet Program, a joint effort between WHOI and the Commercial Fisheries Research Foundation based in Rhode Island. Together, the two have been engaged in a long-term data collection effort to track changes occurring over the continental shelf waters.

AUBREY: So both of these research fleets involve commercial fishermen that go out on their normal day-to-day operations of fishing.

DANIEL: That’s Aubrey Ellertson, a research biologist and the foundation’s program liaison.

AUBREY: We give them equipment and the tools to collect real-time datawhether it’s biological data on lobster and crab, or oceanographic, where they’re getting temperature, salinity and depth information.

DANIEL: Normally, Ellertson hears about these warm core rings from Glen. But when one appeared offshore last month, she was pleasantly surprised that the fishermen beat him to the punch.

AUBREY: I had received a call from Peter Spong, he’s one of our members. He was noticing 58°F water on the bottom and it seemed to shut off his jonah crab catch immediately. And so he was really intrigued on what was going on and asked me if I could talk with Glen and notice if there was either a warm core ring or salinity intrusion that was bringing all this really warm water to the bottom.

DANIEL: And Peter wasn’t the only one who noticed. Closer to shore, gillnetter and captain of the Finast Kind II, Rob Walz, began to see the ominous signs of Gulf water.

ROB: There was a massive amount of dolphins around on the surface. There was so little bait around and they were in the area, they were so desperate that they were eating the fish as we were hauling the net.

DANIEL: Were it not for exposure to WHOI’s shelf fleet project, environmental sensors, and experts like Glen, Walz says it wouldn’t have been as easy to interpret what was going on.

ROB: “Where’d the fish go? Where are they?” Well, it’s pretty much explained right there and it all has to do with the warm bottom temperatures, the salinity. The fish know that they can’t spawn in that area.

DANIEL: Though Walz joined the program only a few months ago, he says he’s already benefiting from the access to data and, like others, is excited to combine his traditional knowledge with scientific perspective from Gawarkiewicz and the foundation.

ROB: Instead of wasting my time, I actually have been doing some work on the boatwhich I’d rather be fishing. It’s actually shown me the benefit to know what’s going on. I almost have the boat back together and I can’t wait to get back out there and get more readings.

DANIEL: Other fishermen have learned to use their temperature and salinity readings to adjust course and look for fish that are likely to withstand the warm Gulf Stream water, even in the winter. In the case of this warm core ring, lobstermen, like Peter Spong who Aubrey mentioned, outfitted their traps to catch species that they knew would thrive in the slightly warmer water. Ultimately they’re saving money, but they’re also feeling like they’re part of the conservation conversation.

AUBREY: I think it’s built a lot of trust and transparency. We give fishermen access to the data always, so they have ownership of the data. And I think these types of projects allow fishermen to connect to scientists that they maybe wouldn’t have met otherwise. So, by meeting Glen they have the ability now to ask questions to try to come to some type of conclusion as to why this phenomenon is happening.

DANIEL: Gawarkiewicz says this bodes well for adaptation in New England’s fisheries, at a time when warming seas will likely mean more frequent warm core rings, something he says is already evident in historical data.

GLEN: The frequency of these intrusions seems to be increasing. In the past 20 years, the average number of rings has gone 18 to 33 rings per yearso it’s nearly doubled.

DANIEL: For Gawarkiewicz, Ellertson, and leadership at CFRF, last month was a milestone in the dialogue between science and commercial fishinga historically fractious relationship. And while last month’s deepwater intrusion has now dissipated, Gawarkiewicz’s excitement hasn’t.

GLEN: I think this is a good example of how, if people are willing to listen, and really learn to value the issues that are going on for another group, really remarkable things can occur.

DANNY: To learn more about the WHOI Shelf Fleet project, you can go to https://go.whoi.edu/shelffleet

For the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, I’m Daniel Hentz.

Image and Visual Licensing

WHOI copyright digital assets (stills and video) contained on this website can be licensed for non-commercial use upon request and approval. Please contact WHOI Digital Assets at images@whoi.edu or (508) 289-2647.