- OLYMPUS DIGITAL CAMERA

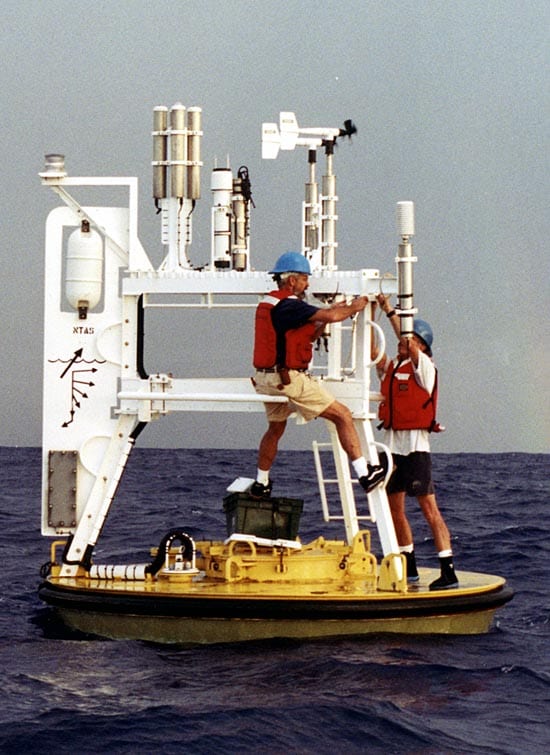

- Early tower designs used a tripod shape, like on these FASINEX buoys from the early 1990s. They left little room for instruments and made it hard to get into the buoy well, where the batteries and data processors are stored. (Photo courtesy Robert Weller, WHOI)

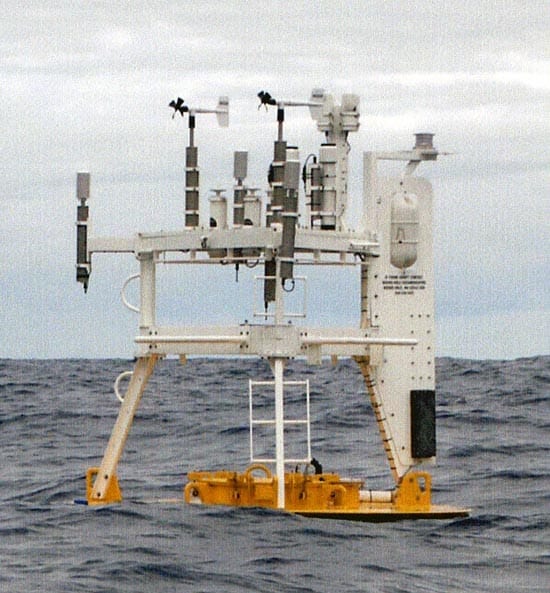

- Over the years, tower tops were enlarged to make room for instruments. But the fiberglass grillwork was eventually abandoned because it disturbed airflow over the sensors. (Photo courtesy Robert Weller, WHOI)

- Two early 1990s buoy designs during instrument burn-in at the WHOI lab. Toroid, or donut-shaped, buoys (right) were replaced by larger aluminum discus buoys (left). By 1995, solar panels were no longer in use. Augmenting battery power with solar energy seemed like a promising idea, but protecting the sensitive panels against waves and salt proved difficult. Instead, engineers reduced the system's power requirement by more than 90%. (Photo courtesy Robert Weller, WHOI)

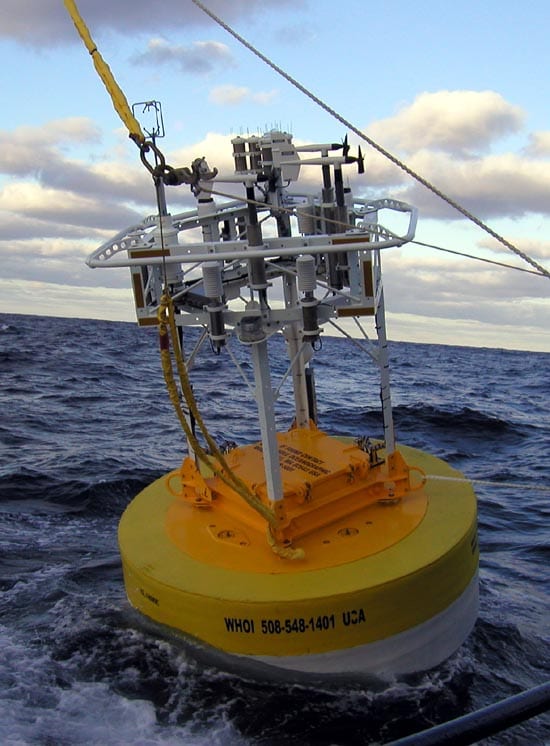

- Aluminum buoys are prone to leaks after long periods at sea. Most newer buoys, like this one off Bermuda, are made of solid Surlyn foam that is much more durable and buoyant. The tower top has been further enlarged from earlier designs, and the square tower provides more headroom for engineers reaching into the buoy well. (Photo courtesy Bob Weller, WHOI)

- The NTAS buoy moored in 2001 in the tropical Atlantic east of Venezuela. The long titanium sensor housings contained an independent battery supply for each sensor. Current ASIMET systems keep all batteries in the buoy well, allowing for shorter sensor housings.

The wind vane at left keeps the instruments mounted on the "front" of the buoy pointed into the wind. The black rectangle on the vane is a satellite transmitter. The white oval is a radar reflector to warn away ships. (Photo courtesy Robert Weller, WHOI) - A buoy ready for recovery at the STRATUS site off Chile in the Pacific Ocean. The aluminum buoy is riding low in the water after a year at sea - one good reason why Surlyn foam buoys, which don't leak, are now routinely used.

The skies are nearly always overcast in this region, making it difficult to study the ocean surface with satellites. ASIMET buoys provide continuous data that would be nearly impossible to acquire otherwise. (Photo courtesy Robert Weller, WHOI) - The CLIMODE buoy ready to start work in the Gulf Stream in late 2005. At deployment, this was the state of the art ASIMET buoy: Surlyn foam hull, rectangular tower, enlarged tower top with open interior, short, battery-less titanium sensor housings. Even this modern buoy has indications of future improvements. The egg-beater-shaped sensor just right of the yellow line is a sonic anemometer. More accurate than the propeller-shaped anemometers, this sensor may be standard on ASIMET systems by 2008. (Photo courtesy Robert Weller, WHOI)

Image and Visual Licensing

WHOI copyright digital assets (stills and video) contained on this website can be licensed for non-commercial use upon request and approval. Please contact WHOI Digital Assets at images@whoi.edu or (508) 289-2647.