I received some wonderful questions from our two schools in the Netherlands. Thank you to the students of Christine Schaafsma in Kastanjepoort School in Erichem and Gerda Steenbergen in Schateiland School in Gouda. Question 1: We saw the video of the conditions during the storm. Was it scary to be onboard the ship? (Question from the Kastanjepoort School) Answer: Everyone who chose to join this trip on the KNORR was aware that we were going to a stormy part of the North Atlantic and came prepared for rough seas. This is a case where your attitude makes all the difference. I found the storm to be exciting and the wild movements of the boat to be like a free roller coaster ride. I couldn’t wait to get to the bridge, which has the best views of the ship, to take photos and just watch the power of the wind and waves. I envied the fulmars (seabirds) who swooped and soared in the howling winds. It was not scary but I will admit to being worried that someone might be injured in a fall, or that I would fall into a table of people eating lunch in the mess (dining area of the boat). Sleeping on a roller coaster, though it may be fun, interferes with sleep so there were a lot of tired people the day after the storm ended. (Although it is Norwegian, I encourage students from other countries to view Sindre’s storm video under “Reisebrev” #12, on our website that these students are referring to.) To see how bad our weather could really get, see the website for the 2008 KNORR trip to this area: https://www.whoi.edu/page.do?pid=28735 and, look for Ben’s storm video coming soon.

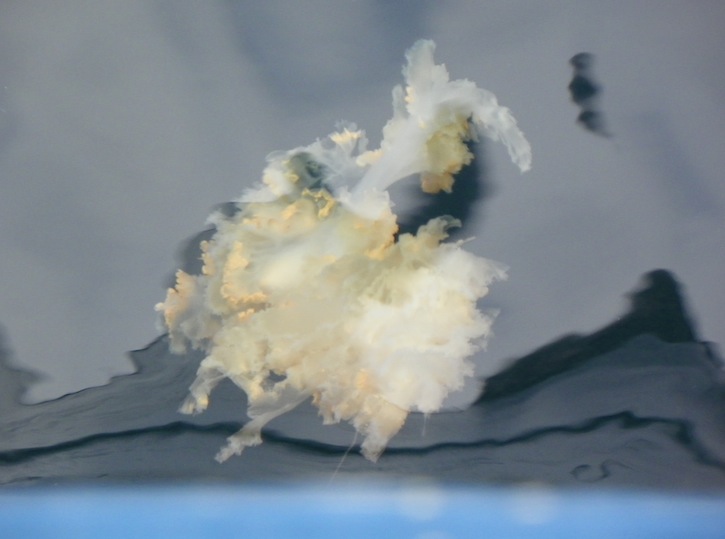

Answered by Pat Keoughan, Outreach Team Question 2: Are you also studying life in the water, like fish? Do you see a lot of special animals during the cruise? (This question came from both schools.) Answer: I’m so glad you asked this question. There is no biologist aboard so I appointed myself to be resident wildlife observer. The northern fulmar is a seabird that seems to love this cold, wet windy environment. We see them flying by in the worst weather and gathered in the hundreds on the water, preening, arguing and just hanging out when the sea is calm. They have been our constant companions, even flying around the ice lights last night when we were watching an aurora. If you look at Rachel’s iceberg photos you will see sprinkled across the ice hundreds of kittiwakes, a pygmy, oceanic gull. They are beautiful little birds who we sometimes see flying with or sitting in the water among the fulmars. One sunny day when we were going very slowly because a mooring was being deployed off the stern of the boat, several came aboard. Other birds that have been sighted are northern gannetts, a greater shearwater and a murre who dove too fast to be identified further. A great cormorant was spotted in Siglu Fjord, Iceland by Sindre and can be seen on his tab in his entry # 10. Last, a dead eider duck was found by the National Geographic photographer, Rob, when he climbed into the crows nest, above the flying bridge, to get some good pictures. We understand a few of them flew into the bridge windows as we left Reykjavik. We’ve had several, brief, marine mammal sightings. A whale expert could probably have identified them at the distance we saw them. Dallas reports seeing a minke whale just before we entered Eyja Fjord, Iceland. Before that, the most recent sighting was a group of 3 or 4 on August 30th. They seemed small and sleek and we argued over they’re being orcas or dolphins. Later, looking at photo closeups, we decided they were probably dolphins but couldn’t make out the species. The most interesting animals, in my opinion, have been the jellies we get to see often, moving with the currents, when the sea is calm. There is no reference book in the library on these brainless, heartless, invertebrates. You’ll just have to look at my photos. Maybe a student reading this can identify some or all of them and let me know? I will continue to be on the lookout for any wildlife that shows up. I am particularly fond of Atlantic puffins and know they are somewhere up here in the North Atlantic. Thank you, again for asking this question.

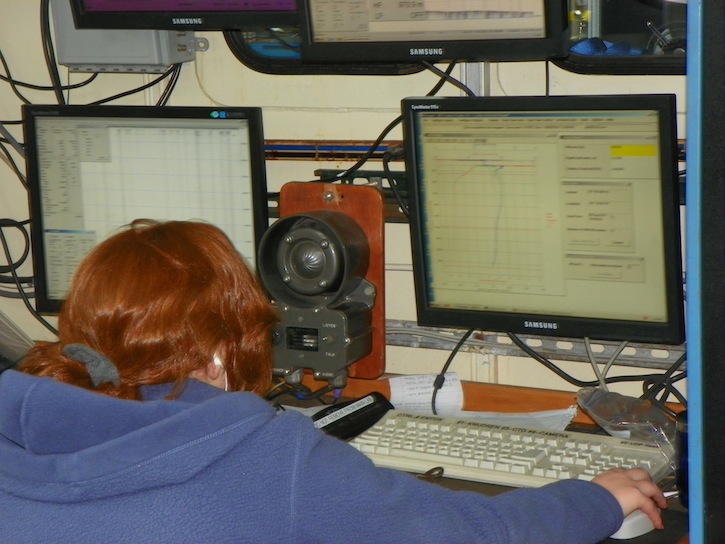

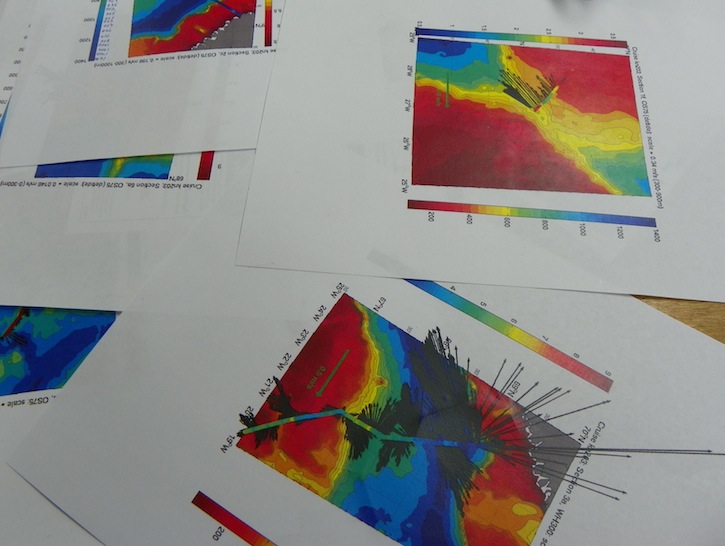

Answered by Pat Keoughan Question 3: Why is the warm ocean water going northwards toward the North Pole and the cold water to the south pole? (Question from the Schateiland School) Answer: The short answer is because of the Gulf Stream. An extension of the Gulf Stream System separates from the main flow in the vicinity of the Grand Banks. Though this is well known, it is less clear exactly why it happens. One theory is that the Grand Banks steers the current in a northeasterly direction. It’s called the North Atlantic Current (NAC). It carries about 25 million cubic meters of warm, salty water every second past the British Isles and, farther, the coast of Norway. This is one of the clearest examples of the relationship between ocean circulation and climate. The British Isles and especially Norway should be much colder than they are given their latitude. But when the west winds blow over the warm water, they carry the NAC warmth ashore, and literally change the climate of those places. It’s important to note that if all that flows north, then an equal amount of cold water must flow back south. Most of it flows at depth through the Denmark Strait. There it becomes the Deep Western Boundary Current (DWBC) that flows back south under the Gulf Stream and on toward the equator. In fact, one theory about why the NAC flows north is because it interacts with the DWBC, and this causes it to diverge from the Gulf Stream’s main flow. Answered by Dallas Murphy, Writer, Outreach Team Question 4: Do you only use computers to do your measurements? (Question from the Kastanjepoort School) Answer: The computers on board are used to store, view and work with the information collected by the different oceanographic instruments used by the scientists for this cruise. The ADCPs, CTD’s, current profilers, microcats and other instruments have electronic sensors that record the measurements the scientists need. Once back on board, the data in the instruments is transferred to the computers much like you would transfer photos from your camera to a computer. There are instruments used that don’t go overboard, but like the instruments that do, their data goes into a computer,too. These include the salinometer used by Dave Wellwood. He takes the water collected by the CTD which has been drained into small bottles, puts a sample of it into the salinometer which then determines the salinity of that bit of water. There are also salinity measurements for the same water that were transmitted to an onboard computer from the CTD itself, through its sensor, as it moved down and up the water column. Carolina Nobre does the computer work that compares Dave’s measurements with the CTD’s to come up with a final measurement. Built into the KNORR is an ADCP, and a thermosalinograph which samples the surface water for temperature and salinity. Computers are very useful and necessary, but they do not get the measurements of the water for the scientists. They do allow them to see, organize and use those measurements for their science. See Dallas’s Journals #3 and #9, Rachel’s slide shows Mooring Hardware, Mooring Operations and CTD’s, and Ben’s video, Mooring

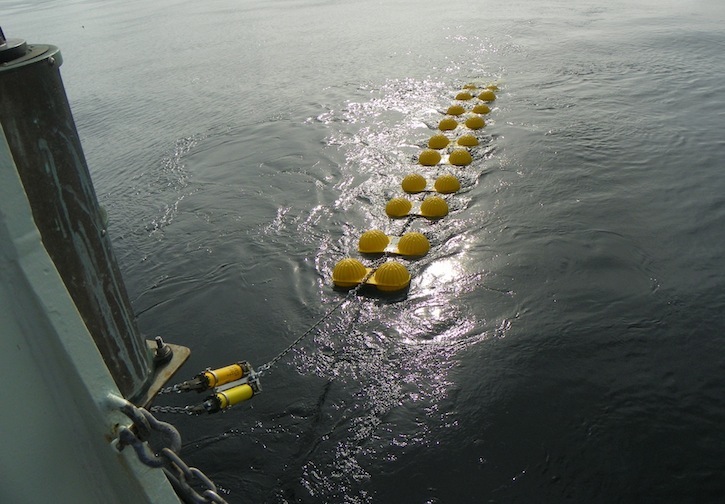

Answered by Pat Keoughan Question 5 : How does an acoustic release work? (Question from Schateiland School) Answer: It is a wonderful thing to be able to put a mooring on the bottom of the sea, leave it there for a year collecting information for you, then come back to get it the following year. But, how do you get the instruments along 700 meters of wire deep under the surface, connected to a 2000 pound anchor on the bottom, back onboard your ship? The answer is an acoustic release. This device is connected to the mooring and linked to the anchor. It is the last part of the mooring to be put on before the anchor. It is built to respond to a series of coded sounds from the ship (that has used a GPS to arrive very close to where it was left a year before) . The code that says “wake up” is punched into a deck box which sends the sound through a wire into a hydrophone that sends the coded sounds, like morse code, into the water. If the acoustic release has survived the year, it is wired to send back a coded message that the deck box receives. It’s message says, “I’m awake ,what’s up?”. The scientist at the deck box punches in the code with the important message...”RELEASE “ which goes into the hydrophone and broadcasts into the sea. The acoustic release is wired to respond to this code that it is releasing, then unlatch its jaws from the anchor chain. Without the anchor holding it down, the entire mooring, including the acoustic release, floats to the surface. Sharp eyes on the deck are on the lookout for the top float, always large and brightly colored, to appear on the surface. The mooring is brought on board with its float, all it’s instruments and bringing up the rear is the reusable acoustic release. The acoustic releases are tested before being put on a mooring about to be deployed, making sure they are responding to the codes including the first, that puts it to sleep. American ships often put two on a mooring so there’s a good chance that at least one of them will release it. Each has six digit codes and no two are alike. (acoustic = being set off with sound waves) Sindre has an interview,#11 under Reisebrev in English, describing the acoustic release, Dallas has information and a photo by Rachel in his Journal #3, Ben’s video Moorings has more informtion.

Answered by Pat Keoughan with assistance from Dallas Murphy and Sindre Skrede Last updated: December 27, 2011 | |||||||||||

Copyright ©2007 Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, All Rights Reserved, Privacy Policy. | |||||||||||