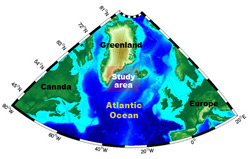

The accepted theory has held that a current flowing down the East Greenland coast delivered most of the water to the strait. It sounded reasonable. Besides, this region was so under-measured no one had enough data to offer another hypothesis. But then in 2004 two Icelandic oceanographers, Drs. Jonsson and Valdimarsson, found intriguing evidence of an unknown current. That doesn’t happen very often these days; in fact, it’s almost unprecedented. The current seemed to pass over the north slope of Iceland and then flow into the Denmark Strait. The Icelanders were certain enough of its existence to give it a name—the North Icelandic Jet. Then during a follow-on expedition in 2008, WHOI oceanographer Bob Pickart verified its existence with more extensive measurements. Not only is this a new current, not only does it flow into this important Denmark Strait—it supplies fully half the water that exits the strait to form the return-flow current. At least that’s the hypothesis. It remains to be proven. That’s what this cruise is all about.

For the first time ever, we will lay a string of instruments across the entire Denmark Strait. These will remain in the water for a full year gathering new data to answer long-delayed questions. That done, we’ll spend the rest of the month-long cruise aboard the WHOI research vessel Knorr searching for the origin of the North Icelandic Jet. This truly international team of ocean scientists, including the original discoverers, postulates that the origin of the current lies somewhere north of Iceland, but they don’t know for certain. No one does. So in this sense, ours is a voyage of exploration different only in objective from those of the legendary Arctic explorers. They sailed in search of new lands and sea routes; we go in search of new waters. We hope you’ll use this website, its text, photos, and videos, to follow along. It’s liable to be cold out there and stormy. But then heavy wind and wild, icy seas have always been major characters in the grand story of Arctic exploration. (The Principal Investigators: Steingrimur Jonsson, Robert Pickart, Laura de Steur, Kjetil Våge, and Hedinn Valdimarsson.)

Last updated: September 3, 2011 | |||||||||||||

Copyright ©2007 Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, All Rights Reserved, Privacy Policy. | |||||||||||||