It was an experiment they hoped would never happen. But when it did, they were poised to respond. In 2008, a multi-institutional team of researchers launched a long-term study to explore the lush but little-known communities of corals, anemones, crabs, worms, fish, and other organisms that thrive on the seafloor in the Gulf of Mexico. The goal of the research team, led by Pennsylvania State University biologist Chuck Fisher, was to begin to understand these deep-sea oases of life by searching for rocky seafloor areas, shipwrecks, oil rigs, and other hard foundations where coral communities develop and by examining the diversity of animals in them. But there was another, perhaps unstated, purpose that was always in the back of team members’ minds. “I’m not sure if it was ever written large,” said Chris German, a geochemist at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI), “but pretty much we were funded to understand what the unperturbed environment would look like, in preparation for that terrible day that might come one day, where there was an accident, and you wanted to say, ‘Well, what was the impact?’ ” That terrible day occurred on April 20, 2010, when the Deepwater Horizon drill rig exploded, leading to the largest oil spill in United States history. Just months earlier, German, Fisher, and WHOI biologist Tim Shank had visited deep-sea ecosystems in the northern Gulf. Federal officials began calling soon after the explosion, Shank said, “to say, ‘You’ve been out there recently. You have the baseline observations for what the corals, and the animals living with them, and the environments, were like prior to the spill. We want your knowledge. In fact, we want you to go out and assess the impact.’ ” “We didn’t really know what we were going to find when we went back out,” Fisher said. “We didn’t know if we’d even see an impact. But there is a variety of scenarios where we could, and the only way to find out is to go down and take a look.” (See video "Assessing the Impacts".) Diversity in the deepThe Gulf of Mexico has one of the world’s most productive fisheries, and it is bordered by some of the fastest-growing counties in the U.S. It is the country’s single largest source of oil and natural gas. And it is also home to species of deep-sea animals, including many that have yet to be identified. Over the course of the spill, some 4.9 million barrels of oil and 2.2 million gallons of dispersants ended up in the Gulf. Ironically, many deep-water communities get their start thanks to some of the same stuff that humans want from the Gulf: hydrocarbons. In places on the bottom of the Gulf, methane and other hydrocarbons naturally percolate up from sub-seafloor reservoirs and seep out of the ocean floor. These so-called “cold seeps” are quickly colonized by bacteria feeding on the hydrocarbons and other chemicals. In the absence of sunlight and photosynthesis, the materials provide a source of life-sustaining chemosynthetic energy. One of the metabolic byproducts of these methane-eating bacteria is calcium carbonate (similar to chalk or clamshells). This material cements grains of the soft, muddy seafloor together, forming islands of hard, rocky ground on which corals can gain a foothold. The corals survive by feeding on particles that fall down from above or that drift past in the water. The corals then provide foundations for other life to flourish in the deep. “Few people know we have deep-water corals in our oceans,” Shank said. “They are extremely diverse and can form reefs that support lots of animals, a lot of diversity—more than 2,000 species worldwide. We don’t know much about the ecology of these corals, but we do know they can live a long time and are extremely vulnerable to disturbance, like fishing trawlers, mining, or oil contamination. We also don’t know what happens to the animals that rely on the corals if the corals are disturbed.” Catching a rain of particlesThe original five-year research project was funded by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and the Minerals Management Service, the predecessor of the present-day Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, Regulation, and Enforcement, to learn how drilling might affect deep-sea life in the Gulf. As part of the project, the team had been scheduled to return to the Gulf in October 2010. But that was not soon enough for German, who focused on how deep-sea ecosystems are sustained by two sources of energy: methane seeping up from the seafloor and particles raining down from the ocean surface. In September 2009, German had put out a pair of sediment traps directly above a deep-sea community in the Gulf to examine what was sustaining its growth. These funnel-shaped instruments are equipped with a rotating stage holding a series of cups to collect sinking organic matter that serves as food for the non-photosynthetic, non-chemosynthetic corals. The final cups were scheduled to close on July 2, 2010. In the week following the explosion of Deepwater Horizon, German saw the surface slick drift north until it was directly over one of his traps. So Scott Worrilow, manager of WHOI’s Subsurface Mooring Operations Group, was dispatched to the Gulf on an NSF-funded Rapid Response cruise to deploy two replacement traps—one beneath the surface slick and the other farther to the west. The new traps continued collecting samples at both sites as the spill progressed and the slick grew. One of the traps failed, but fortunately the one beneath the slick was fine. It was retrieved and additional traps were deployed. When all the collected material is eventually analyzed, German should have an uninterrupted series of data from September 2009 to September 2011, encompassing both the natural seasonal changes in food reaching the bottom and any disruptions caused by the oil. The detritus in those cups could help answer some difficult questions. Did material from the surface slicks sink to the seafloor and affect the filter-feeding animals there? Did oil coating the sea surface block the sun and interrupt the regular supply of food on which deep-sea life in the Gulf relies? Or, conversely, sinking oil may have provided hydrocarbon-eating microbes with “a whole bunch of free lunch at the bottom of the ocean,” as German put it. A return with JasonIn October 2010, the research team returned with the remotely operated vehicle Jason, as planned. Everything appeared normal on the bottom of the Gulf for most of the cruise, but on the last dive of the three-week mission, Jason happened on a new deep-sea coral community. It was located about 7 miles southwest of the Deepwater Horizon, in the same direction as a plume of hydrocarbons flowing from the broken wellhead, which other WHOI scientists had mapped in June. Shank was helping Jason pilot Matt Heintz collect samples on the final dive when he noticed a large red “bubblegum” coral that appeared to have lost tissue, exposing its white skeleton. “The coral next to it was covered with this brown, flocculent stuff,” he said. Instead of healthy-looking brittle stars draping the corals' branches, the scientists also noticed uncharacteristically white brittle stars tightly coiled around the branches of the corals. “I’d never seen this kind of posture anywhere among the dozens of other coral sites in the Gulf, never seen this coloration before,” he said. “They just didn’t look right at all.” “We stopped everything and said, ‘Something weird is happening here, it’s not clear what. This is the closest we’ve been to the well, so let’s just stop and treat it as a crime scene,’ ” Shank said. “ ‘We’re going to spend the rest of our dive here and make sure we document this really well and get important samples for analysis back in the lab.’ And that’s what we did.” Enter AlvinWithin weeks of the spill, Shank, Fisher, and other members of the Gulf team had submitted a proposal to the National Science Foundation Rapid Response program to fund an additional research cruise a few weeks after the October voyage. By good fortune, the human-occupied submersible Alvin was already scheduled to be in the Gulf and had a window of availability in December. A few weeks later, Fisher and German, who is also director of the National Deep Submergence Facility at WHOI, found that another vehicle could also be made available in December: the autonomous underwater vehicle Sentry. It was quickly enlisted to scout by night for deep-sea coral sites that Alvin could investigate by day. On four Alvin dives, the scientists meticulously mapped, sampled, and photographed more than 40 corals in the “unhealthy” coral community that they had previously visited with Jason, as well as a second, apparently healthy site nearby that Sentry found. Dan Fornari, director of the WHOI Deep Ocean Exploration Institute, hustled to bring an ocean-bottom time-lapse camera into play. It was set on the seafloor to help document any subsequent changes at the site. The research team continues to look for more ways to turn their preparation and fortune into knowledge. Various members will return to the Gulf at least four times in 2011, to search for more coral communities and assess the extent and persistence of damage caused by the oil spill on the marine ecosystem deep beneath the surface. “A critical issue for us to learn about is the coral communities’ resiliency and their ability to recover,” Shank said. “They are fragile, and growing less than a micron a year, they can take hundreds, if not thousands, of years to grow back. Will these coral communities die out? Will some species recover and some not? This is going to be a study site for years to come. We haven’t done enough, and that’s why we’re going back.” Originally published: May 5, 2011 Last updated: August 14, 2013 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

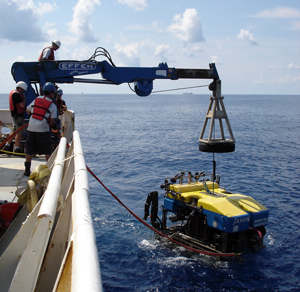

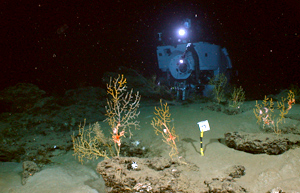

Copyright ©2007 Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, All Rights Reserved, Privacy Policy. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||