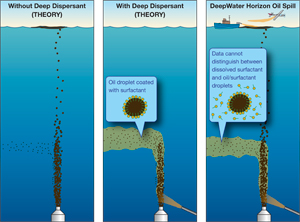

In the aftermath of the Deepwater Horizon disaster in April, marine chemist Elizabeth Kujawinski recognized that a technique she had developed for entirely different reasons could readily be adapted to track the chemical components of oil from the spill, as well as the dispersant used to try to clean it up. Kujawinski brought into play a device with a powerful 7-tesla magnet (seven times stronger than the average MRI) and an intimidating name: a Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance mass spectrometer, or FT-ICR-MS. It can detect and measure vanishingly tiny amounts of an individual compound in a mixture containing tens of thousands of compounds. Kujawinski spearheaded the grant proposal to install the FT-ICR-MS at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) in 2007. Since then she and WHOI colleagues Melissa Kido Soule and Krista Longnecker have been using it to develop highly sensitive analytical methods to reveal the mishmash of organic matter dissolved in seawater. These molecules—either made or used by marine microbes and other organisms—are like bread crumbs that can lead researchers to key biochemical pathways that make the entire ecosystem run. In research published online Jan. 26, 2010, in the American Chemical Society journal Environmental Science & Technology (ES&T), Kujawinski and colleagues showed that the highly powerful mass spec and their method were also well suited to detect, measure, and definitively identify minute quantities of chemical compounds from the Deepwater Horizon spill, including a compound in the dispersant Corexit. The dispersant has been used often in small amounts on the ocean surface to break down oil clumps and make the oil easier to clean up. But never has so much been used before, and never before has the dispersant been released in the deep ocean. Kujawinski and colleagues’ method is 1,000 times more sensitive than that used by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency to track Corexit and could be used to monitor the dispersant over longer time and distances, she said. As such, it provides a means to answer some key questions: What happened to the approximately 800,000 gallons of the dispersant released in the deep sea? Was it effective? Might it have impacts on the environment, deep-sea coral communities, and deepwater fish such as tuna? The researchers also detected DOSS in even lower concentrations (parts per billion) in a plume of oil and natural gas that flowed 3,000 feet deep in a southwesterly direction away from the broken wellhead. That indicated that the dispersant did not itself become randomly dispersed, but rather became trapped in the deepwater plume of oil and natural gas. “The decision to use chemical dispersants at the seafloor was a classic choice between bad and worse,” Valentine said. “And while we have provided needed insight into the fate and transport of the dispersant, we still don’t know just how serious the threat is; the deep ocean is a sensitive ecosystem unaccustomed to chemical eruptions like this, and there is a lot we don’t understand about this cold, dark world.” Oil can contain more than 100,000 compounds with different physical structures, chemical properties, and molecular weights. As soon as oil from the damaged Deepwater Horizon rig began gushing into the ocean, it no longer acted as a unified liquid; rather, individual constituents of the oil acted in their own ways. Some compounds evaporated quickly. Others were consumed by bacteria. Some persisted, and of those, some (the proverbial “oil-and-water-don’t-mix” variety) remained in droplets or clumps. But other components of oil have electrical charges, and these so-called polar compounds bond with similarly polar water molecules. The FT-ICR-MS can identify and measure these hard-to-detect dissolved chemicals. “Our goal is to identify compounds in the water that could serve as tracers of the oil in the coming months and years,” Kujawinski said. That ability will help researchers elucidate what happens when oil and water do mix, as they have in the Gulf of Mexico. The FT-ICR-MS accomplishes this by measuring the mass of atoms and molecules in compounds down to the fourth number past the decimal point. So while most mass specs can distinguish between compounds weighing between 407 and 408 atomic mass units (amu) and between 408 and 409 amu, for example, the FT-ICR-MS can detect a substance with a mass of 407.0259 amu. That’s precise enough to identify the singular collection of atoms—the one possible compound—that together could have that mass. It’s like being able to find—in a crowd of people weighing between 145 and 150 pounds—the one guy who weighs 146.3531 pounds. —Kate Madin, with additional reporting by Joel Greenberg Kujawinski, Valentine, Kido Soule, and Longnecker were joined in the study by Angela K. Boysen, a summer student at WHOI, and Molly C. Redmond of UC Santa Barbara. The work was funded by WHOI and the National Science Foundation. The instrumentation was funded by the National Science Foundation and the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation. Originally published: January 26, 2011 Last updated: August 14, 2013 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

Copyright ©2007 Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, All Rights Reserved, Privacy Policy. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||