|

|

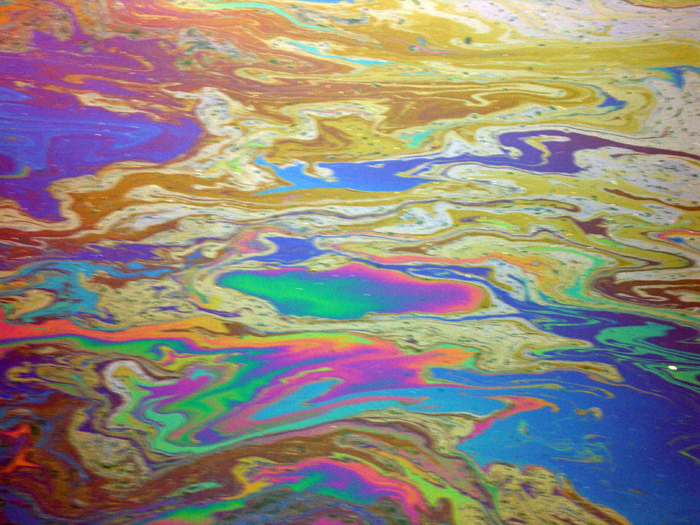

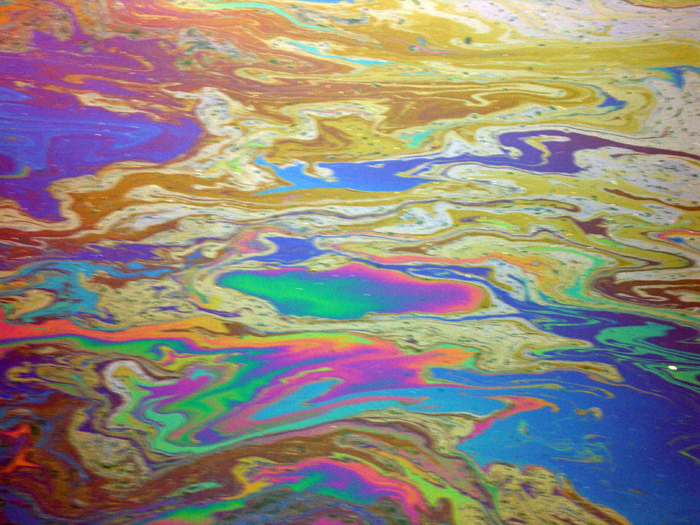

| 1. There’s an oil spill every day off the coast of Santa Barbara, Calif., where oil is seeping naturally from cracks in the seafloor into the ocean. Lighter than seawater, the oil floats to the surface. Some 20 to 25 tons of oil are emitted each day. (Photo by Dave Valentine, University of California, Santa Barbara) |

| 2. In 2007, UCSB scientist Dave Valentine (right) and WHOI scientist Chris Reddy investigated a large mound in the submersible Alvin off the coast of Santa Barbara, California. Using Alvin's manipulator they brought back a large sample of rock from the undersea dome called Il Duomo.They could heft it easily because it was made of asphalt, the solidified residue of oil. (Photo by Molly Redmond, University of California, Santa Barbara) |

3. Natural gas escaping through seafloor cracks off Santa Barbara, Calif., also bubbles up to the ocean surface. The oil seep offers a natural laboratory for scientists to study what happens to oil in the ocean ecosystem.

(Photo by Dave Valentine, University of California, Santa Barbara) |

4. The area around Santa Barbara is very geologically active, because of the movement of the San Andreas and other faults. Extensive faulting or rupturing in the Earth allows oil and gas from subterranean reservoirs to seep up to the seafloor and ultimately into the ocean and to the atmosphere. But some oil solidifies to create asphalt volcanoes.

(Illustration by Jack Cook, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution) |

| 5. The WHOI undersea vehicle Sentry collected sonar data to create this map of the undersea asphalt mound called Il Duomo, the largest of seven similar domes in the Santa Barbara Channel. It covers twice the area of a football field and rises 30 meters, or six stories, above the seafloor. The scale at right is in meters below the sea surface. (ABE/Sentry Group, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution) |

6. WHOI researcher Bob Nelson scoops up a sample of oil that leaked out of the seafloor off the coast of Santa Barbara. Analyzing the sample, they confirmed that the oil at the surface came from reservoirs beneath the seafloor.

(Photo by Chris Reddy, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution) |

7. WHOI shipboard technician Dave Sims guides the sediment grab sampler back on board the research vessel Atlantis with UCSB student A. J. Cecchettini (holding rope). WHOI marine chemist Chris Reddy (foreground) anxiously awaits to see what the grab sampler grabbed.

(Photo by Lea Constan, University of British Columbia) |

| 8. In 2005, marine chemists Chris Reddy of Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) and Dave Valentine of the University of California, Santa Barbara, began studying the Santa Barbara oil seeps. Above, former WHOI research specialist Lary Ball (in scuba gear) collects videotape with an underwater camera while WHOI research specialist Bob Nelson (in snorkeling gear) collects oil samples. (Photo by Chris Reddy, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution) |

| 9. WHOI's autonomous underwater vehicle Sentry was launched from the WHOI research vessel Atlantis off the coast of Santa Barbara, Calif., to search for cold seeps—naturally occurring oil, gas, and other hydrocarbons that are leaking from the seafloor. (Photo by Chris Reddy, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution) |

10. Gas chromatograms of oil sampled off Santa Barbara revealed individual compounds in the oil (the red peaks). Chromatograms from the surface slick oil (top) and the seafloor sediments (middle) show nearly an exact match of compounds, confirming that the oil in the sediments comes from natural oil seeps. The bottom chromatogram is of oil from the Exxon Valdez spill. It is clearly identifiable because it does not contain a compound called bisnorhopane (BNH).

(Chromatograms by Bob Nelson, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution) |

| 11. Oil and methane bubble to the ocean's surface from natural seeps off Coal Oil Point, near Santa Barbara, California. (Photo courtesy of Dave Valentine, UCSB) |